Executive Summary

In March 2024, Michigan Virtual’s AI Lab convened the first AI Statewide Workgroup of education associations in Michigan to identify and coordinate important AI-related trends, challenges, and opportunities facing Michigan school districts. The workgroup includes top leaders from 14 organizations including the Michigan Education Association, Michigan Association of School Boards, Michigan Association of Superintendents & Administrators, Michigan Association of Secondary School Principals, Michigan Elementary & Middle School Principals, Michigan Association for Computer Users in Learning, Michigan Department of Education, and more. Following the recommendations from Michigan Virtual’s Planning Guide for AI: A Framework for School Districts, the AI Statewide Workgroup released the Sample Guidance on Staff Use of Generative AI for K-12 School Districts, and coordinated the distribution of a survey to educators across the state to better understand their needs at this moment in time regarding artificial intelligence.

This survey looked at how educators in Michigan are using AI and what their thoughts are on implementing AI in schools. Over 1,000 educators from various roles, from classroom to district to support organizations, were surveyed. The results of the survey are clear that additional work is needed to support awareness, research, training, and honoring concerns in the field. These results also revealed that many educators are ready to engage in this challenge, with the right supports in place.

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has rapidly ascended as one of the most disruptive and transformative technologies in modern times. In the realm of education, AI holds the unprecedented potential to revolutionize the educational experience for educators and students. The integration of AI into educational systems has the power to create efficiencies, personalize learning experiences, and transform teaching methodologies.

Despite its promising potential, the successful implementation of AI-driven tools and practices in education is not without its challenges. It requires meticulous planning and strategic alignment with a school district’s educational goals, values, and priorities. The dynamic nature of AI technology and its rapid evolution in educational applications necessitate careful and ongoing research to ensure its effective and meaningful integration. Recognizing this, The AI Lab at Michigan Virtual partnered with over a dozen prominent education groups across the state of Michigan on an initiative to enhance our understanding, promote ethical AI use, and identify professional development needs in schools.

By exploring practical insights and strategies, this research aims to equip educators with the tools necessary to navigate the complexities of integrating AI in their districts. As AI technology continues to mature, the educational landscape will undoubtedly undergo significant changes, making it imperative for educators at all levels to stay informed and prepared for this inevitable transformation.

What Exactly is AI?

We use the term artificial intelligence (AI) throughout, but what exactly do we mean when we say “AI”? According to Michigan Virtual’s Planning Guide for AI: A Framework for School Districts, “artificial intelligence refers to computer systems and programs that possess the ability to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence. These systems are designed to simulate intelligent behavior, such as understanding natural language, recognizing patterns, making decisions, and learning from experience.”

Additionally, when we use the term “AI” we refer to both of the following:

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): A branch of computer science that involves the development of intelligent systems capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence. AI enables machines to learn from experience, adapt to new data, and make decisions based on patterns and algorithms.

- Generative AI: This type of AI encompasses algorithms and models designed to produce new content—be it text, images, or video—by learning from vast amounts of existing data.

Current Research Study

This research study was developed based on conversations with, and input from, the AI Statewide Workgroup and guided by the following research questions:

- Are educators using AI in their professional roles, and if so, how?

- Do educators trust AI systems? What are their primary concerns about AI?

- How do educators envision the future of AI?

To answer these research questions, a survey was developed to assess educators’ experiences, challenges, and perceptions of AI in Michigan schools. The survey included demographic questions regarding educators’ roles, ages/levels served, and educational environment; questions assessing trust in AI and AI use; and questions about AI implementation in schools including potential uses and concerns. The survey consisted of a set of core questions that every educator received as well as specific questions based on educators’ identified role. Role-specific questions were for the following groups: teacher, building principal/assistant principal (labeled throughout as building administrators), superintendent/assistant superintendent, school board member, curriculum director, and technology director (collectively labeled throughout as district administrators). The questions for all three groups were similar but worded to apply specifically to each role, i.e. “Are you using AI in your classroom/building/school?”

The survey was shared with, and distributed by, the AI Statewide Workgroup to their membership, generating 1,055 unique responses in approximately 2 weeks. Please note that tables may not add to 1,055 as respondents were not required to answer questions. Additionally, some tables may add to more than 1,055 as respondents could select more than one option. Survey responses were collected in Qualtrics and analyzed in Excel. ChatGPT was used to assist in analyzing and summarizing open-ended question responses.

Findings

Educator Demographics

Table 1 below details the participating professional education association memberships. Eight professional organizations each had over 100 participant responses within the survey, representing a diverse range of educator perspectives.

Table 1. Count of Professional Education Association Membership

| Professional Education Association | Count |

| MEA (Michigan Education Association) | 404 |

| MACUL (Michigan Association for Computer Users in Learning) | 235 |

| REMC Association of Michigan (Regional Educational Media Center Association of Michigan) | 217 |

| MASSP (Michigan Association of Secondary School Principals) | 180 |

| MASB (Michigan Association of School Boards) | 139 |

| MANS (Michigan Association of Non-public Schools) | 132 |

| MASA (Michigan Association of Superintendents and Administrators) | 123 |

| MSBO (Michigan School Business Officials) | 123 |

| MEMPSA (Michigan Elementary & Middle School Principals Association) | 68 |

| MAISA (Michigan Association of Intermediate School Administrators) | 55 |

| Other | 38 |

| MASL (Michigan Association of School Librarians) | 27 |

| MI-ASCD (Michigan Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development) | 27 |

| MAPSA (Michigan Association of Public School Academies) | 25 |

| AFT (American Federation of Teachers) | 21 |

As part of the demographic questions, educators were asked their primary role. Table 2 below provides details of their responses. Teachers represented the largest group of educators, followed by building principals/assistant principals, collectively providing diverse insight into AI perceptions and use in school buildings and classrooms. Additionally, there were nearly 200 respondents in district-level leadership roles, again providing diverse perspectives on district-level AI perceptions, needs, and concerns.

Table 2. Count of Primary Educational Roles

| Primary Educational Role | Count |

| District Level | |

| School Board Member | 62 |

| Superintendent / Asst. Superintendent | 39 |

| School Business Official / CFO | 35 |

| Technology Director | 32 |

| Curriculum Director | 13 |

| Human Resources | 3 |

| Building Level | |

| Teacher | 362 |

| Building Principal / Asst. Principal | 139 |

| Coach / Consultant | 60 |

| Special Education Provider | 29 |

| Library / Media Specialist | 25 |

| School Support Staff | 15 |

| Educational Support Professional | 7 |

| K-12 Peripheral Supports | |

| College Faculty | 16 |

| ISD Administrator | 10 |

| Higher Ed Support Professional | 2 |

| Other (Please specify) | 57 |

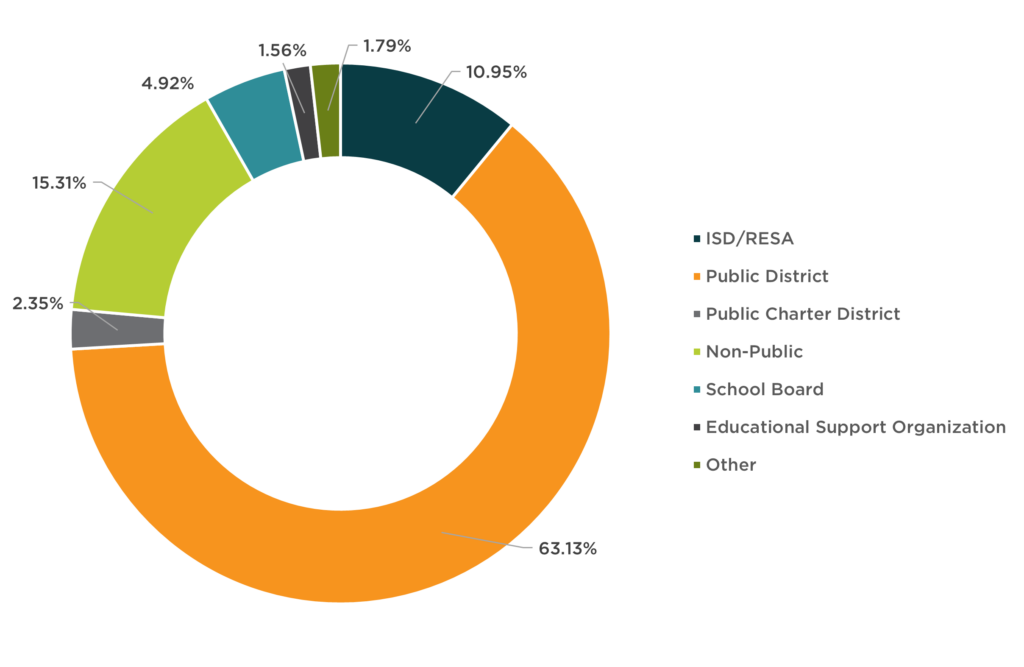

Educators were also asked to identify their primary educational environment. As detailed in Figure 1 below, well over half of educators were from public districts, with a considerable number from non-public schools/districts and ISDs/RESAs.

Figure 1. Primary Educational Environment

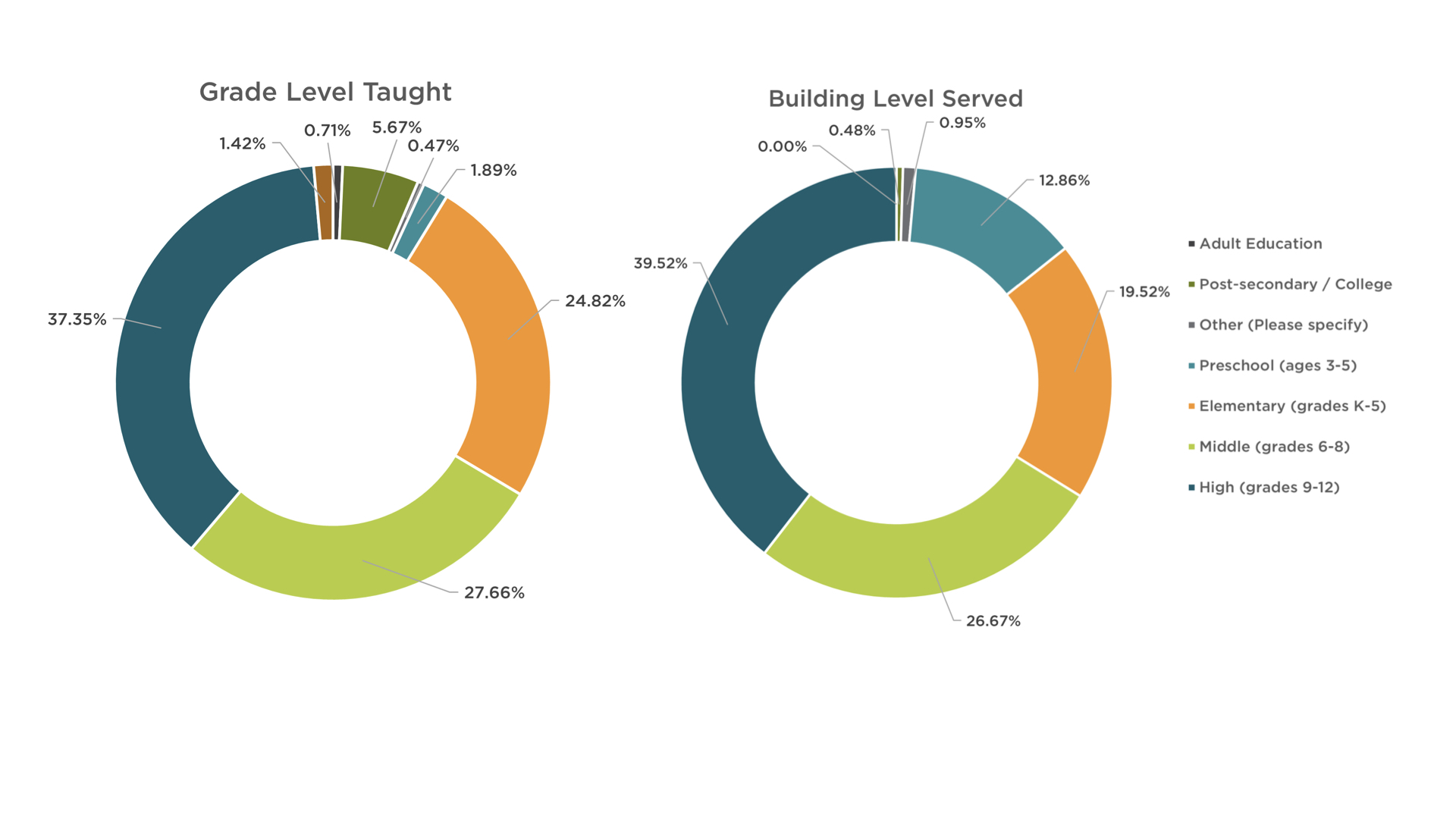

If educators indicated they were teachers or building principals/assistant principals they were asked to identify the grade levels they currently taught or the building levels they currently served. Figure 2 below details these responses. Elementary, middle, and high school teachers were well represented, with a smaller number of respondents in adult education, post-secondary/college, preschool, and career and technical education.

Figure 2. Grade Levels Taught and Building Level Served

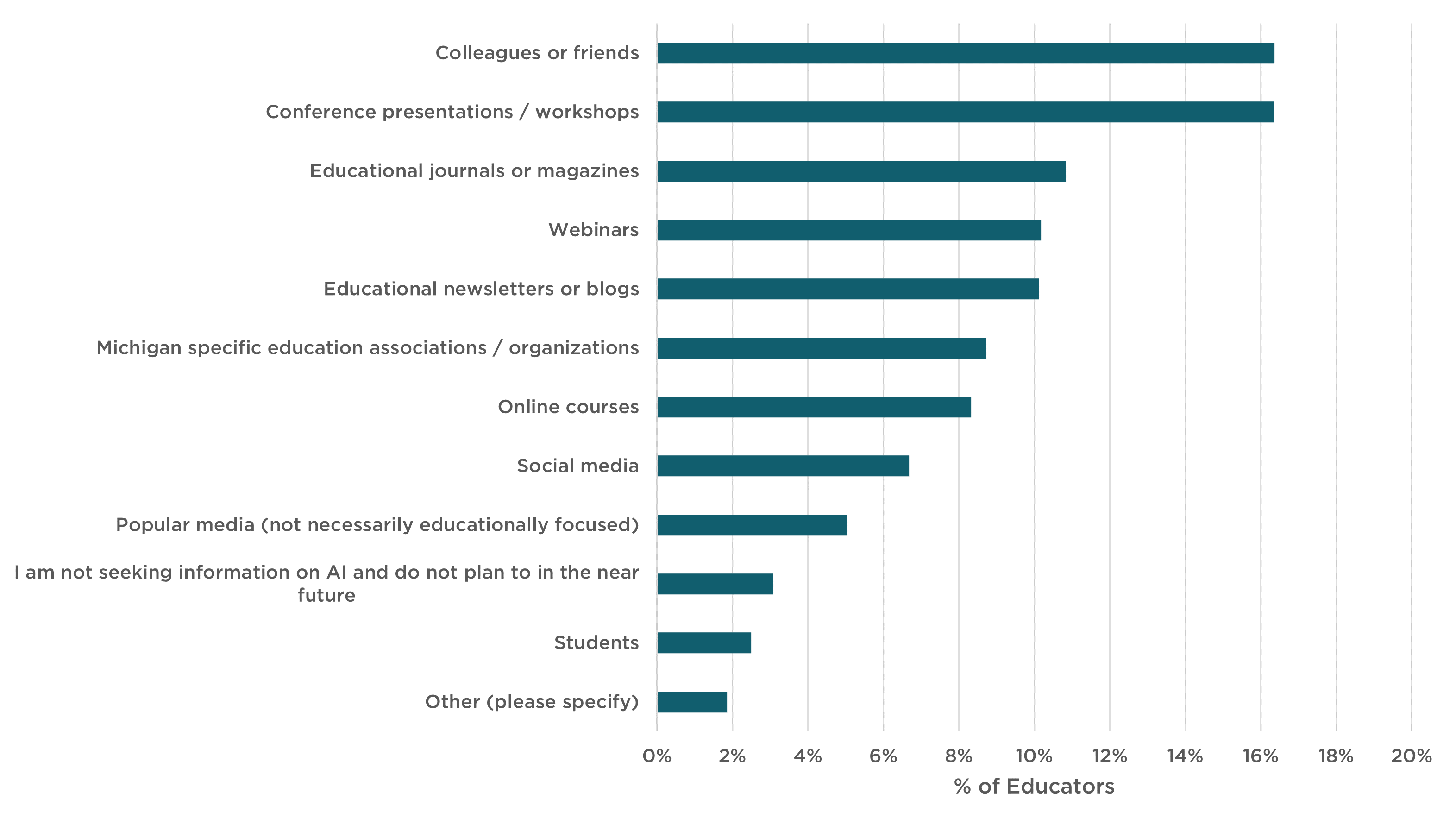

Figure 3. Sources of Information on AI

Are Educators Using AI in Their Professional Roles and if So, How?

Educators were asked if they were using AI in their classroom (teachers), or if teachers were using AI in their school (building administrators and district administrators).

The responses, detailed in Figure 4 below, indicate that building administrators report that teachers in their schools are using AI in some capacity in their classrooms on a much larger scale than reported by teachers or district administrators. Nearly 70% of building administrators indicated that teachers in their buildings were using AI in their classrooms, while less than 30% of teachers reported such use. The reason for this discrepancy is not known. It could be that these figures accurately reflect the context in which these two groups work or perhaps that building administrators are overestimating AI use in their schools. Another possibility is that teachers are underestimating or not identifying AI use as a distinct activity.

Figure 4. AI Use by Role Type

For district administrators who reported that AI was not being used in their schools, those indicating that they were exploring future use of AI were nearly double those who had no future plans to use AI (45.1% compared to 21.2%). Given this data, building and district administrators appear more open or resigned to the inevitability of AI use in their schools.

This trend was not the same for teachers. Of those not using AI in their classrooms, only 31.8% reported that they were exploring future use, while 43% indicated they had no plans for using AI in their classrooms. More so than the other two groups, teachers seemed fairly evenly split between those who were either using AI or planned to and those who had no plans to use AI.

Teachers who indicated that they were using AI were asked to explain how they were using AI in their classrooms. These responses are summarized in Table 3 below. Responses were grouped into categories and examples of each, from responding teachers, are provided for context.

Table 3 highlights various applications of AI in the classroom as reported by teachers, reflecting its diverse role in supporting educational practices. Teachers reported using AI for lesson planning, interactive learning, resource enhancement, and professional development, illustrating its broad utility. Additionally, teachers also reported using AI tools to assist in assessment and feedback, proofreading, and creative writing, and providing targeted support to both teachers and students. These uses suggest that AI can be a multifaceted and valuable tool in education, capable of addressing various needs and improving efficiency, though successful integration requires trust, training, and ethical implications.

Table 3. Teachers’ Use of AI in the Classroom

| Category | Example 1 | Example 2 | Example 3 |

| Lesson Planning & Curriculum Development | Creating standards-based writing prompts, rubrics, and clear instructions. | Developing differentiated lessons to provide tiers of support to students. | Creating decodable passages and sentences for phonics skills. |

| Interactive and Engaging Learning | Introducing AI tools to students and teaching prompt engineering. | Demonstrating the pros and cons of AI compared to traditional search tools. | Integrating AI tools into lessons for interactive tutoring and conversation. |

| Enhancing Classroom Resources | Generating content for differentiated instruction. | Translating texts and changing reading levels to meet student needs. | Developing lesson materials and extension activities. |

| Professional Development and Modeling | Modeling AI use in lesson planning and communication for students. | Teaching machine learning and generative AI units in computer science classes. | Educating students on the ethical use of AI and how to edit AI-generated content. |

| Assessment & Feedback | Providing targeted, rubric-driven feedback on student writing with tools like Class Companion. | Using AI to respond to students’ work submissions and provide feedback. | Creating practice questions and assessment prompts. |

| Proofreading and Writing Support | Teaching students how to use AI for thesis generation, research assistance, and example summaries. | Encouraging the use of Grammarly and grammar practice software like Quill. | Proofreading student writing. |

| Creative Writing and Content Generation | AI-assisted writing structure, support, and feedback on fluency. | AI “interviews” with characters/authors to generate ideas for writing. | Creating visual prompts for oral exams and practice exams. |

| Communication and Administrative Tasks | Generating emails, letters of recommendation, announcements, and newsletters. | Using AI to change wording to professional language in communications with parents. | Creating content and language objectives for lessons. |

| Specialized Uses and Niche Applications | Creating individualized learning pathways and analyzing student progress. | Integrating AI in specific subjects like French language learning by updating old texts to modern language. | Using AI for specific tasks like creating letters of recommendation and Quizizz assignments. |

To understand how educators are—or are not—using AI, it’s important to understand what barriers exist concerning AI implementation. Educators were asked, what barriers, if any, are keeping you from using artificial intelligence (AI) in your professional role, or using AI with your students?

Table 4 below provides a summary of the types of barriers identified by educators alongside examples of each in practice. Among the most prevalent barriers identified are logistical barriers such as lack of training and time constraints, institutional barriers, and ethical barriers such as ethical and privacy concerns, negative perceptions, and lack of trust in AI. In many ways, logistical barriers are easier to overcome as they have clear solutions. If educators feel that they have an overall lack of training on AI, the solution is to provide more training. Ethical barriers, on the other hand, have less clear solutions and take long-term, targeted interventions. Given this, simply addressing logistical barriers may not produce the lasting, institutional change buildings or district leaders desire.

Table 4. Barriers to AI Use in Classrooms

| Category | Example 1 | Example 2 | Example 3 |

| Lack of Training | Need more training before using it in the classroom. | Lack of understanding of how to integrate AI into teaching. | Professional development required to understand AI’s uses and pitfalls. |

| Ethical and Privacy Concerns | Concerns about data privacy (FERPA, IEP/504s, HIPAA). | Worry about inaccurate or biased information. | Ethical concerns about the databases AI is based on. |

| Institutional Barriers | District blocks many AI programs and tools. | Approval is required from the district to use AI. | Lack of district policy or guidelines for AI use. |

| Negative Perceptions and Stigma | Belief that AI use is cheating or lazy. | Concerns about AI reducing students’ critical thinking and creativity. | Stigma and fear around AI from colleagues and students. |

| Time Constraints | Lack of time to learn and apply AI tools. | Time needed to revamp assignments to incorporate AI. | Other priorities taking precedence over learning about AI. |

| Lack of Trust in AI | Distrust in AI’s reliability and accuracy. | Belief that AI is not a trustworthy or honest tool. | Concerns that AI will not replace human teaching effectively. |

| Resistance to Change | Preference for traditional teaching methods. | Belief that students should develop skills without AI assistance. | View that AI is against personal values and beliefs. |

Do Educators Trust AI Systems? What Are Their Primary Concerns About AI?

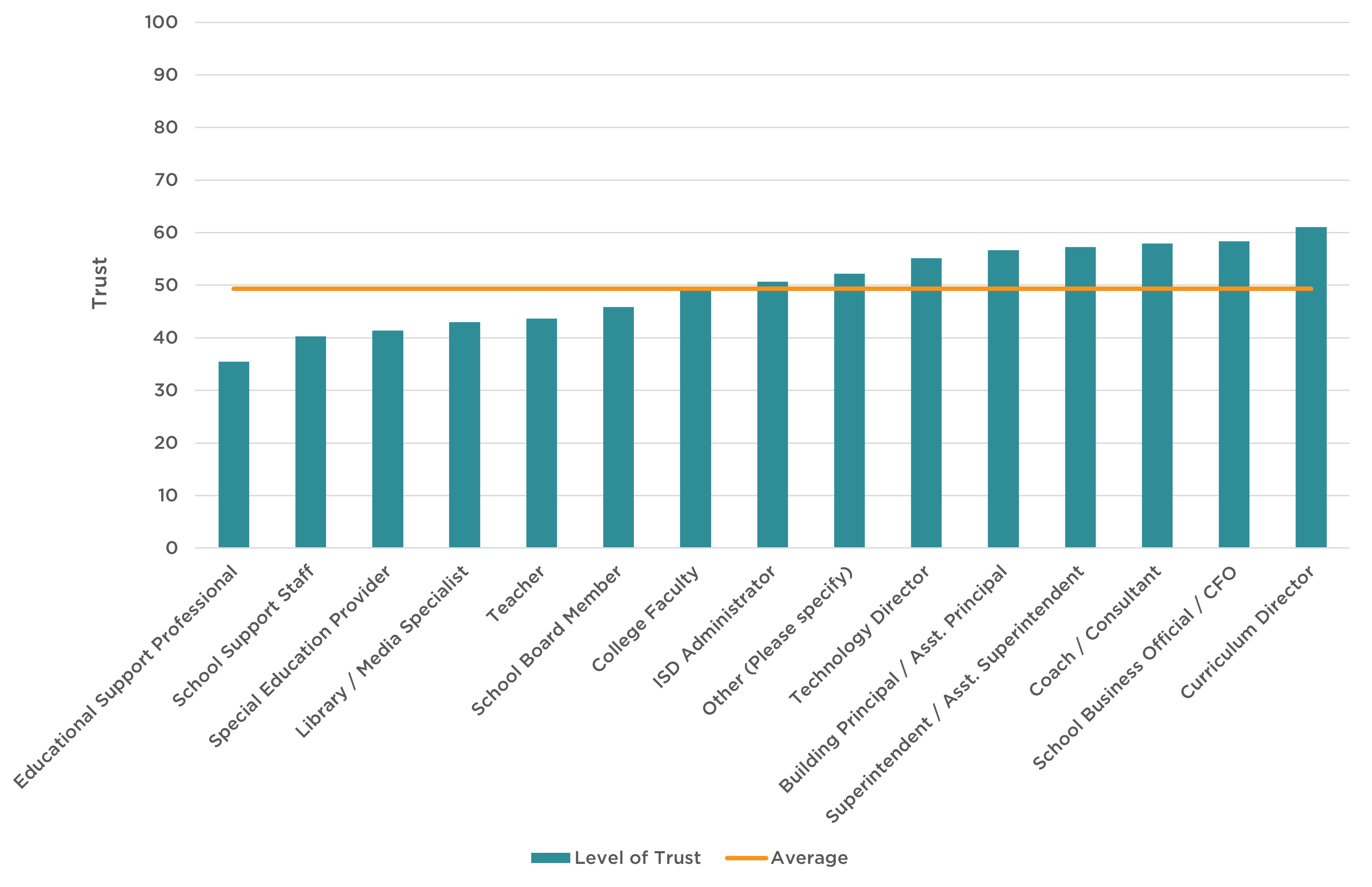

All educators who participated in the survey were asked to rate their level of trust in AI from 0 (no trust) to 100 (complete trust), with 50 indicating a moderate level of trust. The average or mean score for all educators was 49.4 indicating a moderate level of trust in AI overall.

Figure 5 below details the level of trust by role relative to the average level of trust reported by all educators. Curriculum directors (61.1), school business officials/CFO (58.3), coaches/consultants (59.7), and superintendents/assistant superintendents (57.2) on average reported the highest levels of trust in AI. Conversely, educational support professionals (35.5), school support staff (40.3), and library/media specialists (43.0) had the lowest trust. It is important to note, however, that these roles accounted for only 47 out of 1,055 responses. Teachers had the 5th lowest trust in AI with a mean of 43.7.

Figure 5. Level of Trust in AI by Role

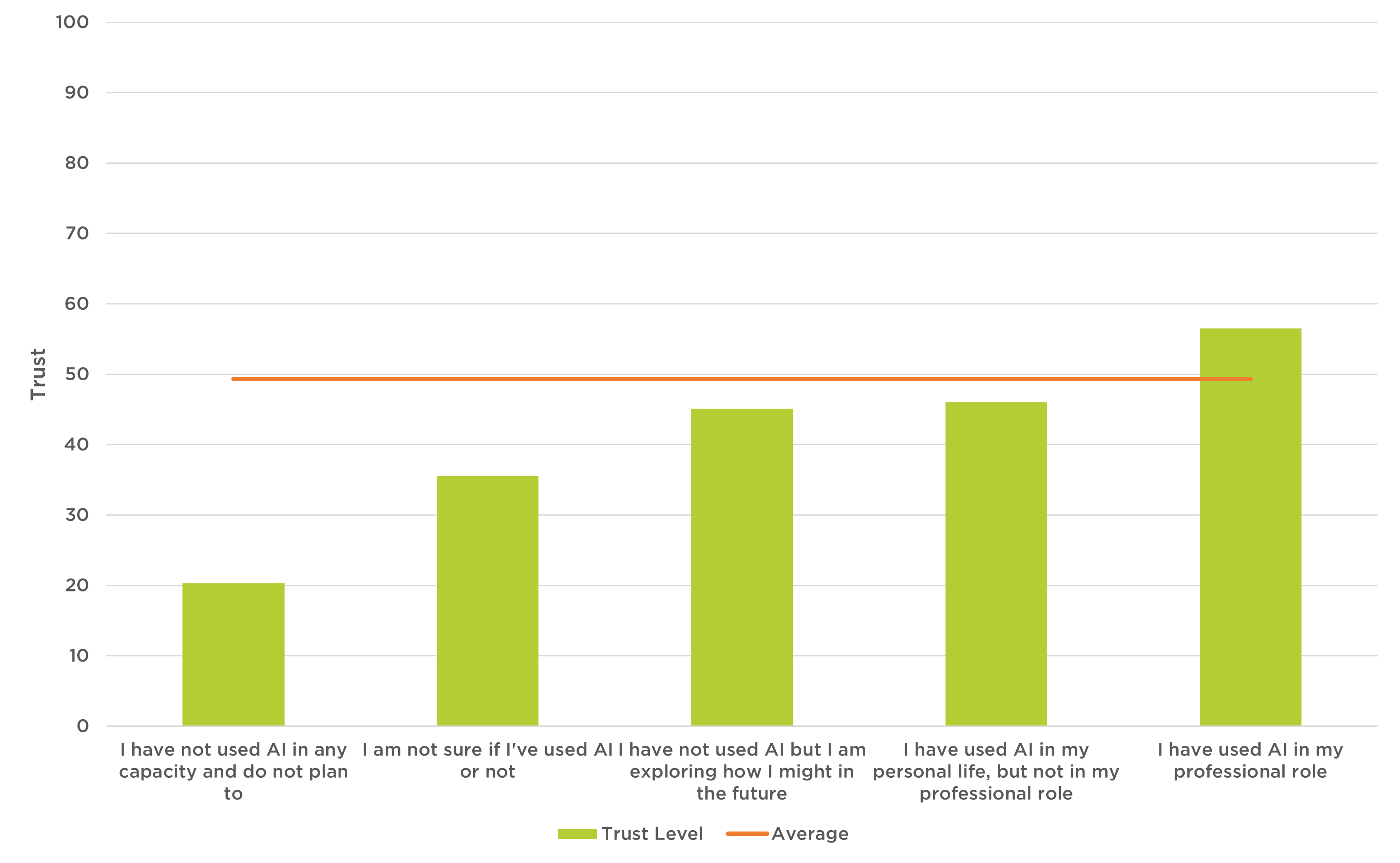

We also looked at the level of trust by experience with AI. Figure 6 below details the results. Unsurprisingly, educators who have not used AI and do not plan to have the lowest level of trust in AI. Conversely, those who have used AI in their professional role had the highest levels of trust. The directionality of this relationship is not clear; however, it is important to note that there are not an insignificant number of educators who have very low trust in AI and have not used AI in any capacity/do not plan to. Additionally, there are a fairly large number of educators who are unsure if they’ve used AI, suggesting that any AI integration plans must begin with trainings that focus on awareness and understanding of AI systems.

Figure 6. Level of Trust in AI by AI Experience

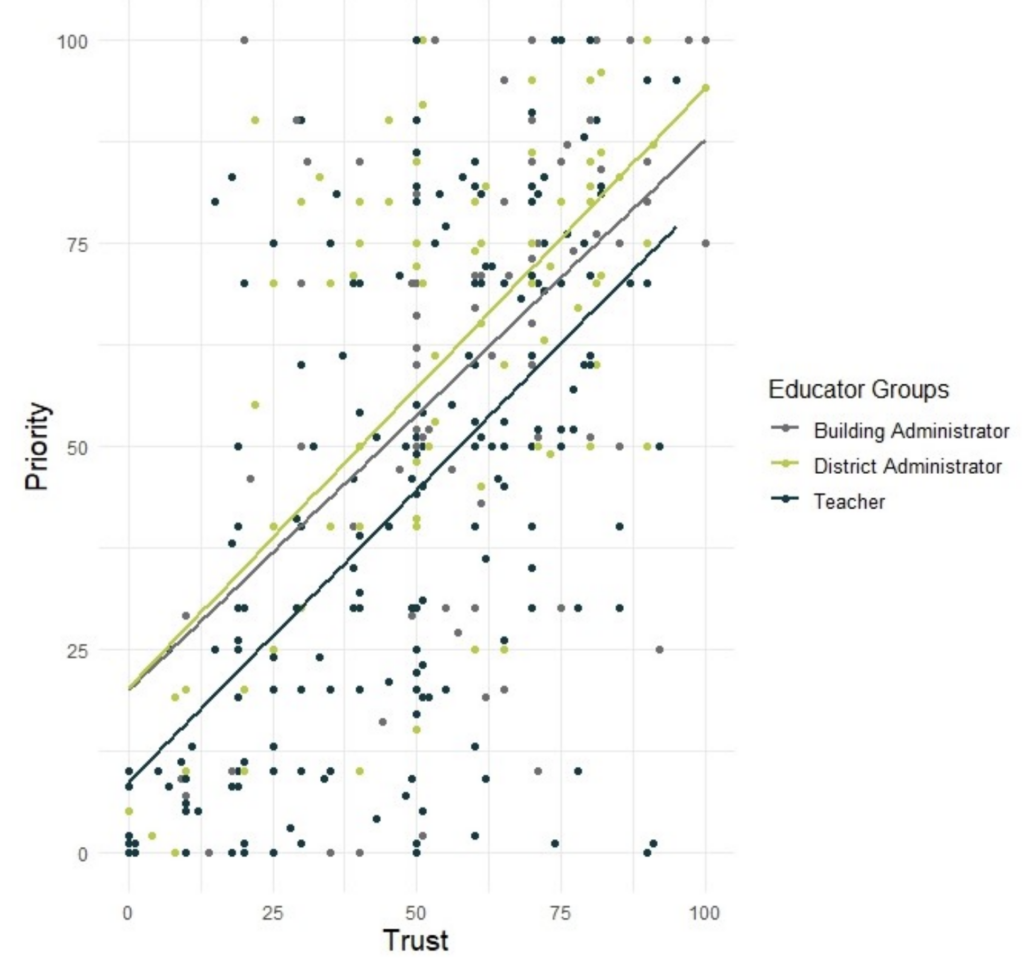

Finally, we looked at the level of trust in AI alongside the level of priority educators placed on AI integration shown in Figure 7. Educators were asked to indicate on the same 0 to 100 scale, what level of priority they place on artificial intelligence (AI) integration in education today. Teachers indicated the lowest level of priority of AI integration, much less than both building and district administrators who both had mean scores above 50. The scatterplot (Figure 7) shows a positive relationship between trust and priority—as trust increases, the priority placed on integrating AI also increases. Teachers reported the lowest levels of trust in AI and the lowest priority for AI integration. Both building administrators and district administrators started at similar levels of trust and prioritization; however, as district administrators’ trust increased, the priority they placed on AI integration slightly surpassed that of building administrators. Educators who have a high level of trust in AI may place increased priority on integration because of the perceived benefits of use, while those with lower levels of trust may be hesitant to place a high priority on integration due to perceived drawbacks and concerns.

Figure 7. Trust in AI and Listing AI as a Priority

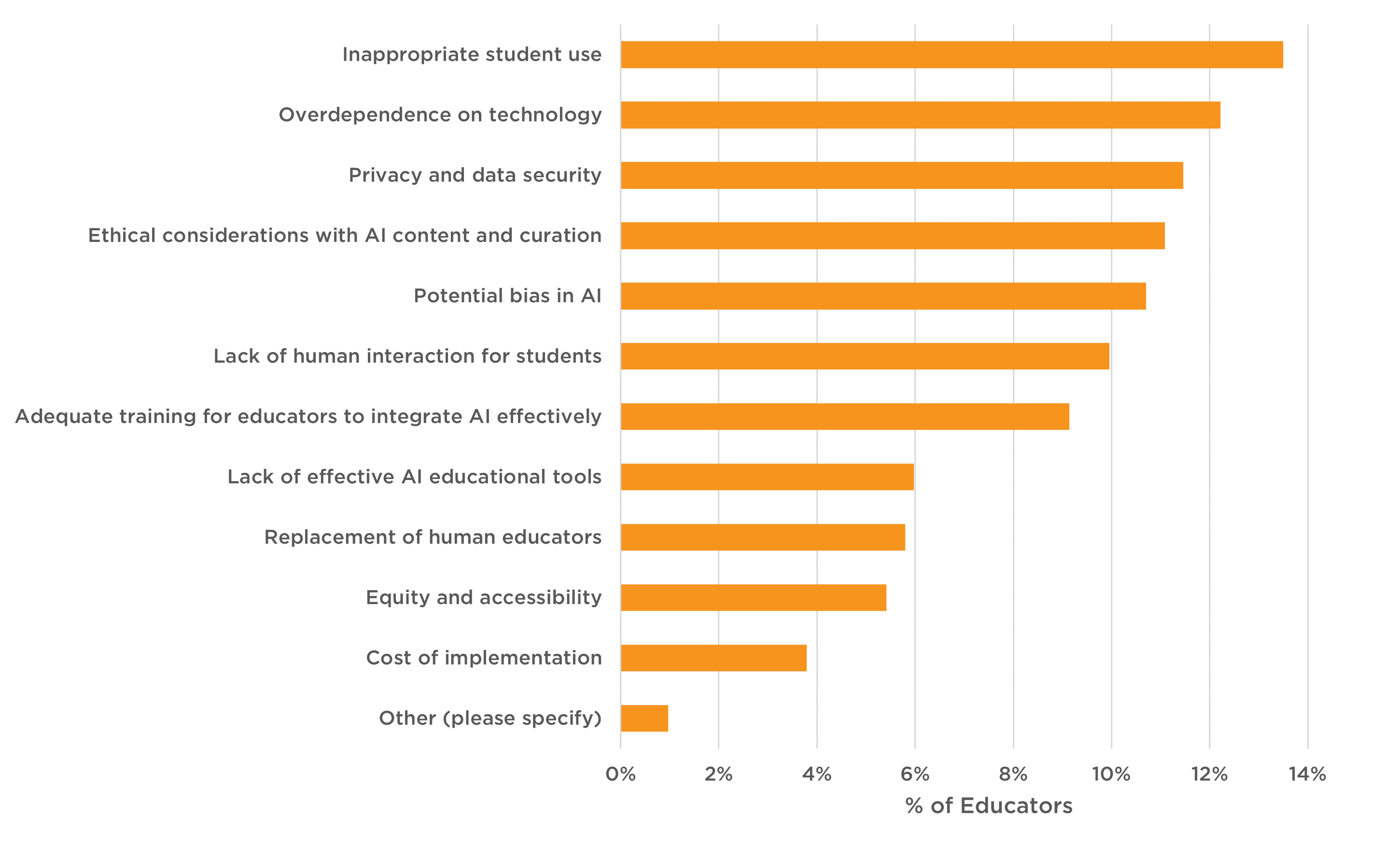

Educators were asked to select all the areas in which they were concerned about AI integration. Figure 8 provides a detailed look at their responses. More than 10% of educators reported concerns around inappropriate student use, overdependence on technology, privacy and data security, ethical considerations with AI content and curation, and potential bias in AI. Educators, while still concerned, reported being less concerned overall about the cost of implementation, equity and accessibility, replacement of human educators, and lack of effective AI education tools.

There was also the option to add additional concerns not listed in the original question. Overwhelmingly, educators indicated that they were concerned about the intellectual and academic impact of AI. For example, they noted concerns regarding AI encouraging intellectual laziness, negative impacts on students’ critical thinking, increased risk of cheating, and accusations of cheating. Educators also reported concerns about the reliability and accuracy of AI results, noting that AI often produces incorrect or inappropriate information, and students might believe all AI-generated content is factual, leading to misinformation.

This data suggests that educators’ concerns are varied but the most pressing tend to be those regarding ethical use (inappropriate student use, cheating, etc.) and less logistical (cost, tool availability, etc.). For schools and districts looking to explore AI use and integration, understanding educators’ specific concerns will be crucial in bolstering trust and confidence in AI.

Figure 8. Concerns Regarding AI

How Do Educators Envision the Future of AI?

As discussed above, building and district administrators place the level of priority of AI integration around 60 out of 100 (57.4 and 59.3 respectively). Nearly 80% of district administrators and nearly 90% of building administrators report that they are currently using AI or exploring future use. Taken together, this suggests that administrators, and to a much smaller extent teachers, regard AI implementation as somewhat of an inevitability and therefore a priority. One that will be necessary to consider in the future, regardless of their level of trust around AI.

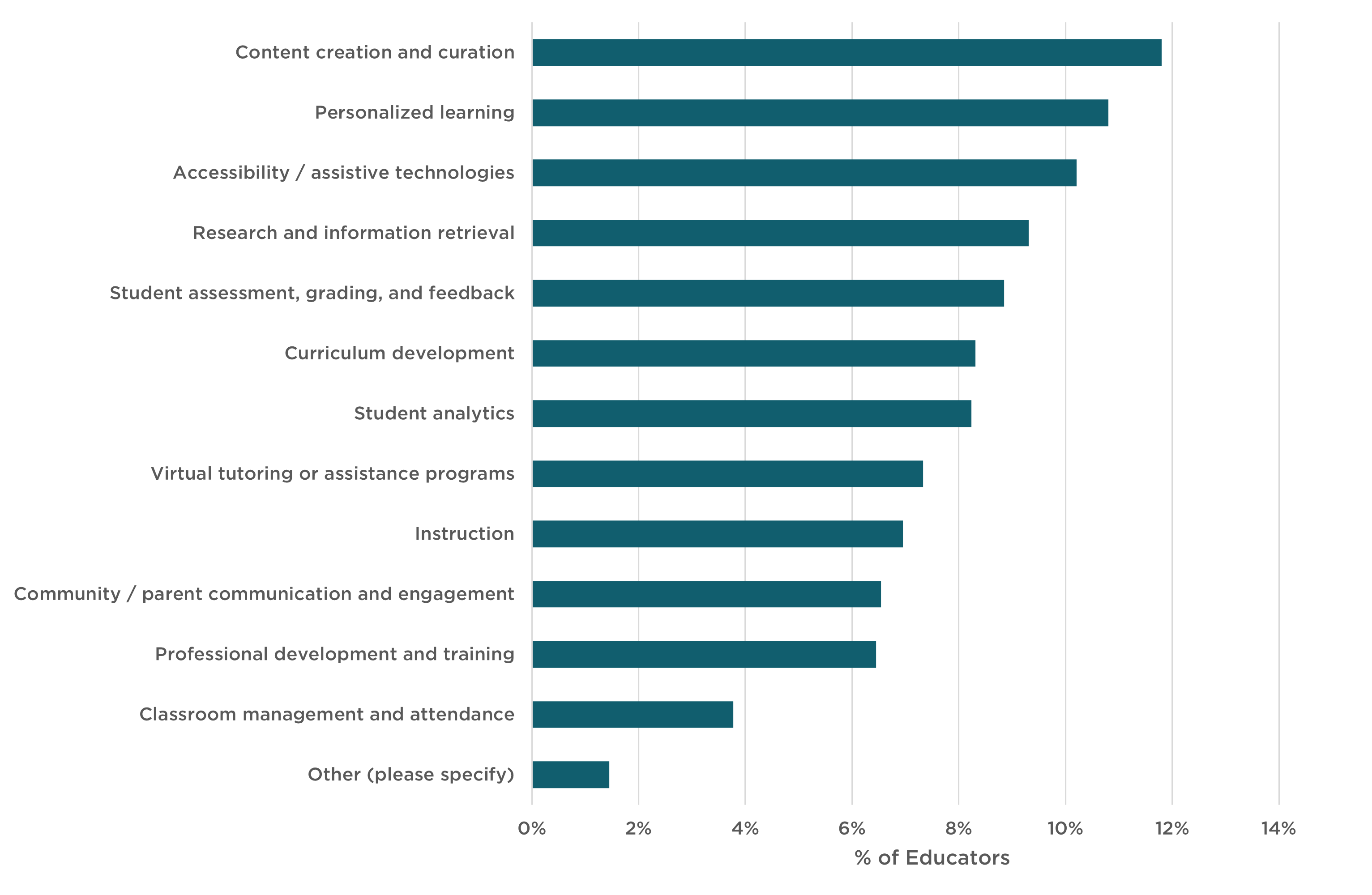

Figure 9. Promising Uses of AI

We also asked all educators in what areas they think AI can be a useful tool. The results are detailed in Figure 9 above. Educators seemed most optimistic about AI assisting with content creation and curation, personalized learning, and accessibility/assistive technology. Educators seemed most optimistic about AI’s ability to help them personalize and differentiate learning and make their content and curriculum more accessible. Teachers seemed less optimistic about AI assisting with some of the more “interpersonal” aspects of teaching such as virtual tutoring or assistance programs, instruction, and community/parent communication and engagement.

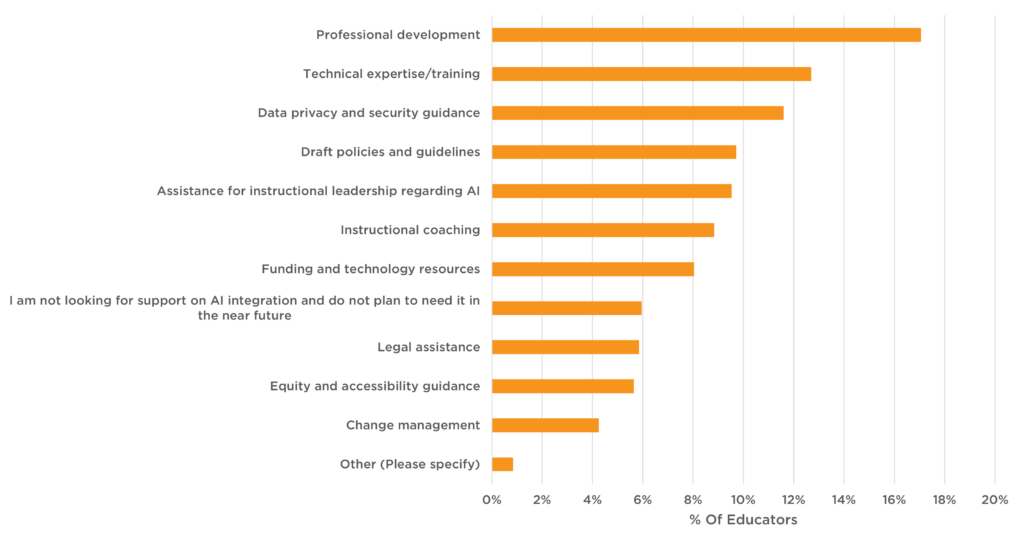

To understand how to better support teachers and schools in AI implementation, educators were asked, in what areas do you need support for integrating artificial intelligence (AI) into your school/district. Figure 10 below details their responses. At the top of the list was a need for support around professional development, followed by technical expertise/training–two areas that are closely aligned. Educators also responded and identified a need for assistance with AI policy, specifically guidance around data privacy and security, as well as draft AI policies and guidelines.

Figure 10. Areas of Support Needed Regarding AI Integration

Key Takeaways

Building and District Administrators Have High Trust in AI and Deeper Experience with AI

Building and district administrators have higher levels of trust in AI and consider AI integration to be a higher priority than teachers. These administrators also have much more experience using AI both personally and professionally than teachers. As such, administrators need to be mindful and patient as teachers may not automatically “buy into” their vision for AI integration. Education leaders can use their experience and vision to lead their buildings and districts but need to be understanding of stakeholder concerns and reluctance towards AI.

Educators Are Using AI in Their Buildings and Classrooms, Regardless of Offical District Policy

Only approximately 30% of district administrators reported that their school, school board, or governing body officially adopted AI policy or guidelines; however, over 50% of educators who responded to this survey reported using AI in their professional role (an additional 15% reported using it personally but not professionally). Educators (not all, but many) are “ahead” of their districts and using AI in their classrooms and schools. Whether or not districts want to pursue AI integration, this data suggests a real need for clear AI policies and guidelines to guide the use that is already taking place.

There Exists a Group of AI Skeptics That Cannot Be Ignored

There is a not insignificant group of educators who have little to no interest, low trust, and are not actively seeking information on AI. Six percent of educators reported that they are not looking for support on AI integration and will not need it in the future, 20% have not used AI and do not plan to, and approximately 10% do not think AI will be used significantly in classrooms in the next 5 years. This group of educators, while not the majority, may possess serious concerns about AI integration and/or be largely apathetic to the potential uses and implications of AI.

Discussions Around AI Are Just Getting Started

A vast majority of educators, over 80%, feel like AI will play a “very significant” or “somewhat significant” role in education in the next 5 years. However, given current experience and use trends, there exists a large gap between how and when educators are using AI now and where they expect to be in the future. Encouragingly, educators reported a strong need for support integrating AI into their schools and districts in the areas of professional development/expertise, data privacy, and draft policy and guidelines among others.

This data also suggests that not everyone is entering the discussion around AI integration with the same experience, perceptions, and concerns. Education leaders will need to assess where stakeholders are and ensure diverse voices are represented—not just those most enthusiastic about AI. One way to ensure diverse perspectives is to include the larger stakeholder community as educators in this survey responded that they valued those voices. Over 50% of educators felt that both students and the larger community should be involved in discussions around AI “always” or “often”, while only approximately 10% of educators felt that these groups should be included “rarely” or “never.” Figure 11 shows a detailed breakdown of how often educators felt students and the school community should be involved in discussions around AI.

Figure 11. Perceptions of How Often Students and Community Members Should Be Involved in Discussions Regarding AI

Final Thoughts

If there is to be one takeaway from this research, it is that there is a vast array of perceptions, concerns, experiences, needs, and levels of trust around AI. Educators see many areas of promise for AI integration but also many areas of concern. Many educators are using AI personally or professionally, but districts may not yet be “caught up” to this reality. Educators have seen educational technology tools come and go for decades now, and while there are a small number who believe AI will not produce radical changes to education, many more are expecting AI to transform it.

This survey is only the start of understanding Michigan educators’ perceptions of AI—many more discussions are needed. While this research focused on educational professionals, key stakeholders such as students and parents were not included; however, they will need to be as districts and schools move forward with AI integration.

We started this report by stating that AI integration requires meticulous planning and strategic alignment with a school district’s educational goals, values, and priorities. This still holds true. AI use is already happening in schools and educators expect this use to increase significantly in the near future. Educators are hungry for more guidance, clarity, and information on AI and how to integrate it into their practice–but they’re also cautious. While the process will not be easy, it is imperative that schools and districts address AI, in some capacity, because leaders, teachers, and students are already using AI, oftentimes without any guardrails in place. School districts have the ability to establish these guardrails to equip educators with the tools necessary to navigate the complexities of integrating AI in their districts while empowering both their staff and students.

Based on this evidence, the AI Lab within MVLRI will continue to provide support and leadership to the AI Statewide Workgroup and others around the following strategies:

- Increase AI awareness and communications

- Pursue ongoing research on AI classroom literacy

- Expand professional learning on AI tools

- Validate and consider potential concerns