Abstract

Positive student-teacher interactions can serve as the basis for strong relationships, which may benefit academic outcomes for students. These relationships may be particularly pivotal early on in students’ experience in a course. Understanding teachers’ beliefs and behaviors surrounding communication and relationship-building can help ensure alignment with best practices, benefiting teachers and students. Through surveys, focus groups, and a review of best practices and Michigan Virtual instructional policies, the current study found alignment between teachers’ perceptions, behaviors, and best practices. Teachers primarily communicated with students through the Student Learning Portal, Brightspace, and email to provide reminders, respond to student-initiated communication, and provide feedback. The top five strategies they used—welcoming tone, clear expectations, personalized feedback, prompt responses, and empathy—align with those they found most effective, though in a different order. Both instructional policies and teacher pedagogy should continue to emphasize best practices for communication and relationship-building.

Introduction

Student success in online courses depends on many intertwining factors relating to the student, course design, instructional pedagogy, and more (Curis & Werth, 2015; Liu & Cavanaugh, 2011; Hosler & Arend, 2012). Cultivating student success in online courses requires a multi-pronged approach (Michigan Virtual, n.d.; Roblyer et al., 2008). Communication and relationship-building are two interconnected pedagogical elements that can play a key role in promoting student success.

Positive student-teacher interactions marked by characteristics such as trust, belonging, respect, support, and connection serve as the basis for building strong relationships (Duong, et al., 2019; Kincade et al., 2020), and these relationships are associated with student engagement (Brewster & Bowen, 2004; Duong et al., 2019) and achievement (Cornelius-White, 2007; Curtis & Werth, 2015; Hambre & Pianta, 2001; Hwang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022; Mensah & Koomson, 2020; Roorda et al., 2011). Instructors of online courses can foster rich student-teacher interactions through communication, feedback, encouragement, and promoting discussion even when they do not interact with students face-to-face (Boston et al., 2019).

Research suggests that high-quality student-teacher interactions are associated with academic achievement as reflected by state test scores (Allen et al., 2013), end-of-course grades (Hawkins et al., 2013), and perceived learning (Caspi & Blau, 2008; Joosten & Cusatis, 2019; Kum-Yeboah et al., 2017; Richardson, 2001). Further, when students are asked to reflect on their learning experiences, student-teacher interactions and communication are often central themes (e.g., Borup et al., 2019). For example, students from traditionally marginalized groups expressed that student-teacher interactions and open communication prompted learning and bolstered their academic self-concept. Having an accessible instructor who provided feedback and support gave students more opportunities to ask questions and created discussions that promoted understanding (Kumi-Yeboah, et al., 2017). Overall, students who receive more interaction with their online course instructors report being more satisfied with their experience (Turley & Graham, 2019). Finding strategies for increasing student engagement and academic success is vital, as research indicates that pass rates are typically lower for online courses than in-person ones (Freidhoff et al., 2024). The importance of teacher-student interaction, in conjunction with research highlighting the importance of student engagement at the beginning of a course (Zweig, 2023), points to a need to better understand how teachers interact with students in the initial weeks of a course and associations with student achievement. Given the positive associations between relationship-building behaviors, communication, and student outcomes, this study aims to understand the nature of teacher-student interactions in Michigan Virtual (MV) courses. The focus will be on understanding the methods, purposes, and outcomes associated with communication during the first four weeks of a course. An analysis of current MV teacher practices and training materials will be conducted alongside a review of best practices to facilitate alignment between theory/research and practice.

The Current Study

Given the positive associations between communication, relationship-building, and student outcomes, this study aims to understand the nature of teacher-student interactions in Michigan Virtual courses. Previous research has shown engagement during the first weeks of a course to be predictive of student outcomes like final grades (Zweig, 2023). As such, examining communication and relationship-building early on (within the first four weeks) may help identify important links to student achievement and opportunities for intervention. An analysis of current MV teacher practices and training materials was conducted alongside a review of best practices to facilitate alignment between theory/research and practice.

The goals of this study produced the following research questions:

- How often, by what means, and for what reasons do teachers communicate with students within the first four weeks of a course?

- How often do students initiate communication? What percentage of student-initiated communications receive a teacher reply within 24 hours?

- What is the frequency of one-to-one communication? What is the frequency of one-to-many communication?

- Is the frequency of teacher communication associated with students’ final course grades?

- What are teachers’ beliefs about relationship-building in a virtual learning environment? How are these beliefs reflected in the way they approach instruction in the first four weeks of a course?

- What are considered best practices for online teacher-student communication? How does this align with Michigan Virtual teacher training, behaviors, and recommendations?

Methods

Researchers conducted a mixed methods study to address the research questions outlined above.

Qualitative Methods

Researchers conducted five focus groups of full-time Michigan Virtual teachers to understand communication and relationship-building practices used by teachers in the first four weeks of an online course. Grouped by content area, researchers met with groups of 4-7 teachers for approximately 15 minutes each. Each group was asked 2-3 different open-ended questions that pertained to their experiences communicating and building relationships with students in their online courses, specifically during the first four weeks.

Quantitative Methods

A survey of 19 questions assessing teachers’ frequency and perceptions of communication and relationship-building practices in the first four weeks of a course was sent out to all full- and part-time Michigan Virtual instructors. 97 instructors responded to the survey (74 part-time and 23 full-time instructors), with approximately 40.00% of the sample having between 6 and 10 years of online teaching experience. To obtain more detailed information about communication in Michigan Virtual online courses, a member of MV’s technology integration team pulled data such as teachers’ incoming/outgoing messages and students’ course enrollment details, including final course grades, from the Student Learning Portal (SLP). Analyses were restricted to the three most highly enrolled courses (according to enrollment data from Michigan Virtual’s 2022-23 annual report) in each of the core subject areas of English Language and Literature, Life and Physical Sciences, Mathematics, and Social Sciences and History (review Appendix A for a list of these 12 courses). This allowed researchers to analyze the relationship between teacher communication frequency and final grades. Taken together, the SLP data, survey data, and focus group data provided researchers with a holistic and rich look at relationship-building and communication practices in online courses.

Results

Results from this mixed-methods study are organized and presented by research question.

How often, by what means, and for what reasons do teachers communicate with students within the first four weeks of a course?

Teachers’ communication tool use

According to survey data, within the first four weeks of a course, the top three communication tools used daily by teachers were BrightSpace (LMS), the SLP (Student Learning Portal), and emailing individual students. At the top of the list of communication tools teachers reported not using were ‘other’ tools, text messages, and phone calls. Table 1 depicts how often teachers use specific tools to communicate with their students in the first four weeks of a course.

Table 1. Percentage of Communication Tool Use Among Educators

| Communication Tool | Daily | 4-6 times per week | 2-3 times per week | Once a week | Less than weekly | Did not use |

| BrightSpace | 31.96% | 82.50% | 19.59% | 30.93% | 51.50% | 41.20% |

| SLP | 25.77% | 15.46% | 21.65% | 25.77% | 11.34% | 0.00% |

| Email individual students | 20.62% | 14.43% | 21.65% | 17.53% | 20.62% | 51.50% |

| Other___ | 13.21% | 18.90% | 37.70% | 37.70% | 0.00% | 77.36% |

| Office hours | 41.20% | 10.30% | 51.50% | 45.36% | 21.65% | 22.68% |

| Email students one-to-many | 30.90% | 51.50% | 10.31% | 40.21% | 32.99% | 82.50% |

| Teacher feed | 30.90% | 10.30% | 20.62% | 74.23% | 10.30% | 0.00% |

| Video conferencing (e.g., Zoom) | 10.30% | 0.00% | 92.80% | 17.53% | 36.08% | 36.08% |

| Text messages | 10.30% | 41.20% | 10.31% | 82.50% | 29.90% | 46.39% |

| Phone call | 10.30% | 30.90% | 10.31% | 82.50% | 36.08% | 41.24% |

During focus group conversations, teachers described how they use some of these tools to encourage reciprocated communication with their students, specifically during the first few weeks of a course. For example, teachers often make introductory videos in their Teacher Feed to “let students know I am a real teacher” and record personalized video responses to students’ introductory discussion board posts to help build rapport. One teacher shared how they send students messages in the SLP “introducing myself, making sure students know various ways they can contact me, and providing a few tips for success in the course.” Several teachers noted using a different communication tool—surveys—to get to know their students better by asking things like their preferred name, pronouns, why they are taking the course, their goal in the course, a bucket list item, and “anything else they think I should know about them, which opens up opportunities for students to share important information.” Teachers use these communication tools to humanize and personalize their interactions with students.

Frequency of teacher-student communication

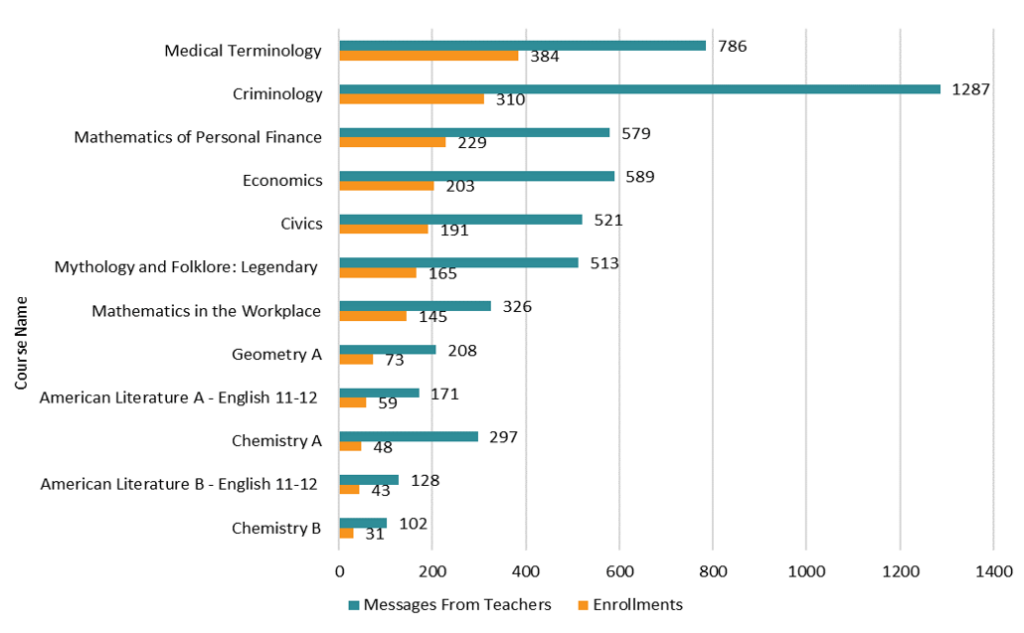

Teachers (n = 45) sent approximately 124 messages on average (M = 124.84, SD = 156.76) in the first four weeks of a course. However, this number varied substantially from three to 721. Looking at the median number of messages, half of the teachers in the sample sent less than 72 messages within the first four weeks, and half of them sent more than 72 messages. Looking more closely at communication patterns indicates that teachers sent an average of about three messages per student (M = 2.83, SD = 1.36). The total number of messages sent by teachers varied by course enrollment size, with teachers sending more messages as enrollments increased. To review the number of messages teachers sent based on course and enrollment, refer to Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Enrollments and Messages by Course

Looking specifically at the number of messages teachers sent to individual students, an average of 119 messages were sent within the first four weeks (M = 119.13, SD = 150.73), with half of the teachers sending more than 70 messages to individual students and half sending less than that. The number of messages sent by teachers to individual students ranged from one to 15. Teachers sent just under three personal/individual messages per student in the first four weeks of a course (M = 2.75, SD = 1.30). Half of the teachers sent just over two messages per student, and half sent less than that.

Reasons for teacher communication with students

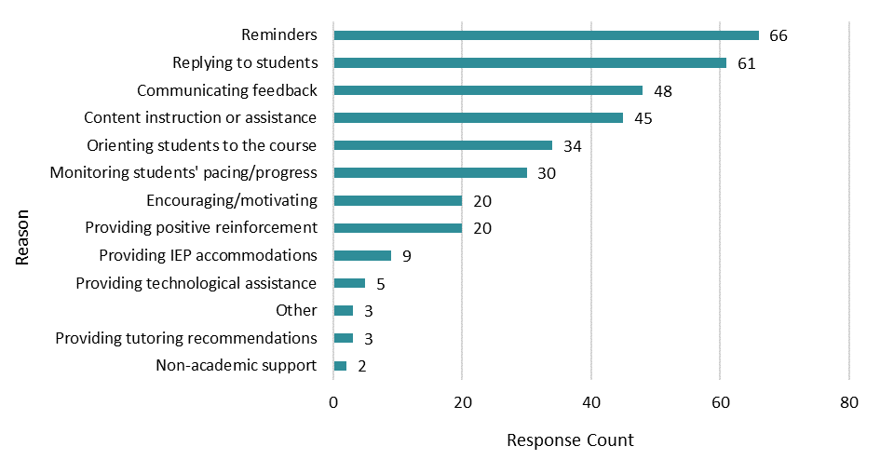

When asked about the top three reasons teachers communicate with students during the first four weeks, providing reminders about assignments, policies, important dates, etc., was selected most often and followed closely by replying to student-initiated communication. The third most common reason teachers communicated with students was providing feedback about student learning. See Figure 2 for a full breakdown of reasons teachers communicated with students during the first four weeks of a course.

Figure 2. Reasons for Teacher Communication with Students

How often do students initiate communication? What percentage of student-initiated communications receive a teacher reply within 24 hours?

According to teachers, in the first four weeks of a course, the top three tools used daily by students were the SLP, email, and text messages. Conversely, teachers reported that attending office hours and using video conferencing were communication tools least commonly used by students. Review Table 2 below for information on how often students initiated communication with their teacher(s) via specific communication tools.

Table 2. Percentage of Communication Tool Use Among Students as Reported by Teachers

| Communication Tool | Daily | 4-6 times per week | 2-3 times per week | Once a week | Less than weekly | Did not use |

| SLP | 23.96% | 14.58% | 25.00% | 17.71% | 15.63% | 31.30% |

| 19.59% | 17.53% | 20.62% | 20.62% | 18.56% | 30.90% | |

| Text message | 31.60% | 21.10% | 63.20% | 94.70% | 30.53% | 48.42% |

| BrightSpace | 30.90% | 72.20% | 12.37% | 11.34% | 29.90% | 36.08% |

| Office hours | 21.10% | 0.00% | 21.10% | 12.63% | 25.26% | 57.89% |

| Other___ | 19.60% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 19.60% | 19.60% | 94.12% |

| Teacher feed | 10.50% | 0.00% | 73.70% | 17.89% | 40.00% | 33.68% |

| Video Conferencing (e.g., Zoom) | 0.00% | 21.30% | 53.20% | 13.83% | 24.47% | 54.26% |

| Phone call | 0.00% | 21.10% | 84.20% | 63.20% | 25.26% | 57.89% |

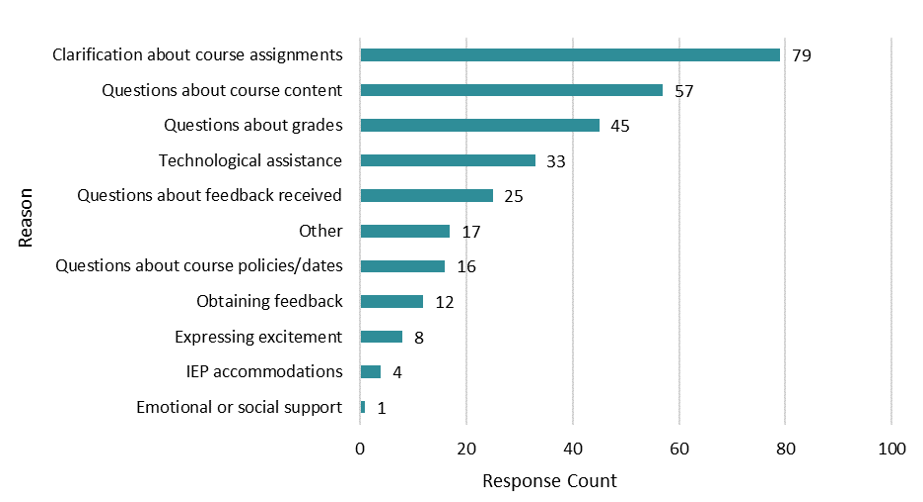

According to teachers, the most commonly reported reason students reached out was to obtain clarification about course or assignment requirements. Questions about course content or grades were also commonly reported reasons students initiated communication. Contacting teachers for emotional or social support was not widely reported in the first four weeks. See Figure 3 to see why students contacted their instructors during the first four weeks. Michigan Virtual policy states teachers should reply to any student communication within 24 hours. Most teachers indicated that this was a reasonable expectation (n = 92, 94.85%) and were able to meet this expectation. Indeed, teachers estimated that, on average, 97% of student-initiated communications received a reply within 24 hours. Some teachers contextualized their responses, indicating this was a reasonable expectation, barring unforeseen life circumstances or students reaching out on weekends.

Figure 3. Reasons for Student Outreach During First Four Weeks

What is the frequency of one-to-one communication? What is the frequency of one-to-many communication?

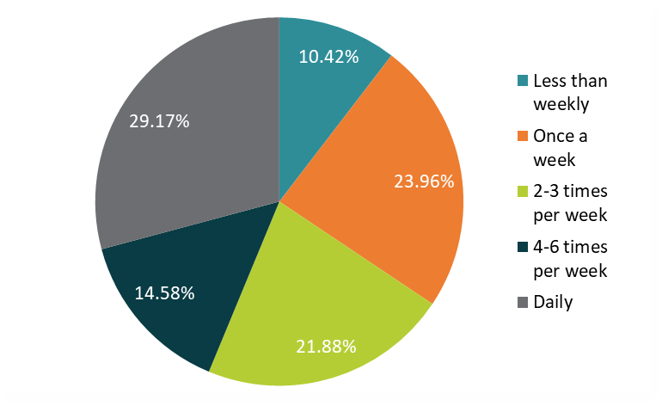

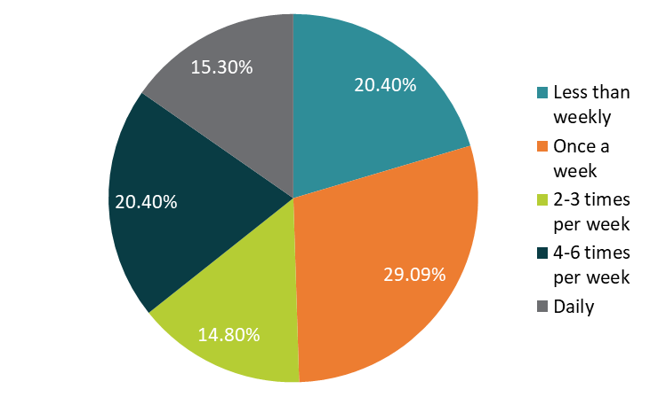

Course-wide teacher-student communication was most likely to happen once a week (29.09%), whereas the frequency of communication with individual students was more distributed. Approximately twenty-nine percent of teachers reported communicating with students individually daily, in contrast with 10.42% communicating with individual students less than weekly. This likely reflects the use of course-wide communication for course updates, announcements, reminders, and messages that apply to all students, whereas individual communication likely centers around providing feedback, replying to student messages, and personalized/individualized communication. Notably, all teachers reported using both types of communication, and no teachers reported a lack of communication during the first four weeks of the course. See Figure 4 for the frequency of teachers’ communication with individual students and Figure 5 for the frequency of teachers’ course-wide communication.

Figure 4. Frequency of Individual Teacher-Student Communication

Figure 5. Frequency of Course-Wide Teacher-Student Communication

Is the frequency of teacher communication associated with students’ final course grades?

While outliers (extreme cases) are typically removed from a dataset before analyses, all students in our sample had completed their courses, and their data represents real cases of students who have completed a semester of online learning. Because of the variation in student performance, analyses were run with and without outliers. While the descriptive information about grades changes based on the inclusion or exclusion of these outliers, the relationship between teacher-initiated messages and students’ final grades remains similar, so the data is presented with outliers included for concision.

With outliers included, students averaged grades of 77.67% (SD = 22.91) in their courses; however, grades ranged from 0.11% to 99.76%. A positive but not statistically significant correlation existed between the number of messages teachers sent to students during the first four weeks of a course and the student’s final course grade (p > .05, tau = 0.005).

To further understand how communication relates to students’ grades, the data was segmented into quartiles (percentiles) based on their grades. Students, regardless of grade, received a similar number of messages from their teachers. Students in the 25th percentile (those with the lowest grades) received the fewest messages (M = 3.15), and students in the 50th and 75th percentile received 3.24 and 3.23 messages each, on average. The means being so closely clustered together suggests very little variation in the number of messages teachers send to students. This lack of variation may have obscured the relationship between communication and final grades.

What are teachers’ beliefs about relationship-building in a virtual learning environment?

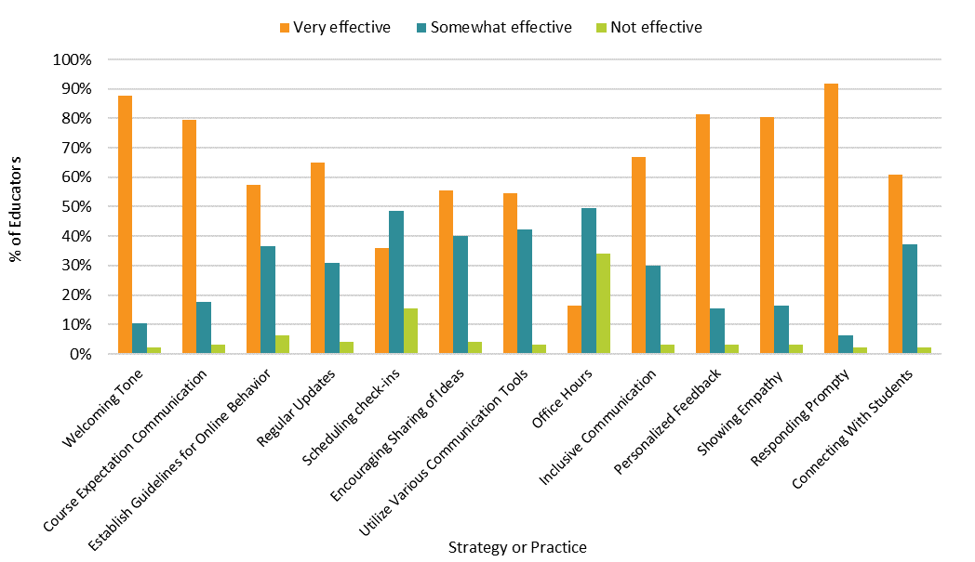

When asked about what practices were effective for building relationships in the first four weeks of a course, responding promptly (n = 89, 91.75%), using a welcoming tone (n = 85, 87.63%), and providing personalized feedback (n = 79, 81.44%) were the most commonly reported strategies that teachers believed were “very effective.” The practices teachers perceived as the least effective (the highest percentages of those strategies teachers indicated were “not effective”) were holding office hours (n = 33, 34.02%) and scheduling check-ins (n = 15, 15.46%). Review Figure 6 below for details on how effective teachers perceived all the strategies and practices included in the survey.

Figure 6. Perceived Effectiveness of Specific Strategies & Practices

How are these beliefs reflected in the way they approach teaching in the first four weeks of a course?

During focus group conversations, teachers acknowledged how important relationship-building is in an online course despite it being more challenging than in a traditional face-to-face classroom. Because there is some “mystery about the person behind the screen,” teachers felt that being positive and aware of their tone was very important. They explained that because of the perceived tone in your online communications, “you may come off differently than you would in person.” Messages delivered online or through email can feel cold or formal, “missing that tone your voice would have delivered if you were face-to-face, so you have to work hard to convey your compassion.” This is consistent with survey results indicating that using a welcoming tone is a practice teachers feel is very effective in relationship-building.

Teachers also indicated that providing personalized feedback—another strategy perceived as very effective when it comes to relationship-building—such as consistently using students’ preferred names in their feedback “seems to go a long way with students.” One teacher mentioned that they try to tie something personal about the student into their feedback so that students know the feedback is directed specifically toward them. Personalizing feedback in this way also helps to emphasize that the teacher listens and pays attention to the information students share.

The survey also asked teachers how effective they perceived specific strategies and practices to be and if they used them during the first four weeks of their online course(s). As expected, there was an overlap between the strategies teachers perceived as very effective and those they reported using in the first four weeks. The top five strategies teachers reported using—using a welcoming tone (100%), communicating course expectations clearly (100%), providing personalized feedback (100%), responding promptly (100%), and showing empathy (97.94%)—are the same top five strategies (just in a different order) that teachers believe are most effective at building relationships with students during the first four weeks of a course.

What are considered best practices for online teacher-student communication? How does this align with Michigan Virtual teacher training, behaviors, and recommendations?

To better understand how Michigan Virtual teachers leverage communication and relationship-building best practices in their online courses, an interview was conducted with Dr. Shannon Smith, Michigan Virtual’s senior director of student learning, alongside a review of Michigan Virtual training materials and recommendations. Dr. Smith explained that Michigan Virtual draws on both the National Standards for Quality Online Teaching (NSQOT) and Danielson’s Framework for Teaching (FFT) and pointed to a document used to evaluate and guide Michigan Virtual online teachers that pulls from both models—A Crosswalk of the NSQ Teaching Standards and the Danielson Framework. These best practices, including those focused on relationship-building and communication, are incorporated into Michigan Virtual’s teacher training materials, behaviors, and recommendations (e.g., The Michigan Virtual Way: Expectations and Success Indicators for Michigan Virtual Instructors).

There was close alignment between best practices drawn from the NSQOT and FFT, recommendations made in the Michigan Virtual Way document, and teachers’ behaviors and beliefs as assessed in the current study. Firstly, most student-initiated communications received a reply within 24 hours. Indeed, responding promptly was the most commonly reported strategy educators endorsed as being “very effective.” In their communications with students, teachers draw on NSQOT and FFT principles by ensuring their communication is focused on supporting students’ academic engagement and success and utilizing various communication methods (e.g., email, SLP, text, etc.). Feedback, which was emphasized across best practices frameworks, was also perceived as crucial by teachers, as evidenced by 81.44% of teachers believing it to be a “very effective” practice. Feedback was the third most commonly reported reason teachers reached out to students and was highlighted in the focus groups as pivotal for student success. Table 3 below illustrates the alignment between what the National Standards for Quality Online Teaching, Danielson’s Framework for Teaching, and Michigan Virtual consider to be best practices related to teacher-student communication, relationship-building, and personalized feedback.

Table 3. Alignment Between Danielson’s FFT, the NSQOT, and Michigan Virtual Best Practices for Communication and Relationship-Building

| Danielson’s Framework for Teaching (FFT) | National Standards for Quality Online Teaching (NSQOT) | Michigan Virtual |

| 3a: Communicating About Purpose and Content Elements of Success: • Purpose for learning and criteria for success • Specific expectations • Explanations of content • Use of academic language While any communication with or between students has a direct connection to many of the components of learning environments, communication related to the purposes of learning, the expectations for activities, and the content itself are essential aspects of instruction that support (or hinder) students’ intellectual engagement and academic success. | B1 The online teacher uses digital pedagogical tools that support communication, productivity, collaboration, analysis, presentation, research, content delivery, and interaction. D4 The online teacher establishes relationships through timely and encouraging communication using various formats. Regardless of who the online teacher is communicating with, effective communication methods are necessary for successful two-way communication. | Return communications within 24 hours of receipt, Monday-Friday. The instructor MUST provide a Welcome Letter to all students (include guardians and mentors) outlining clear expectations for class participation. The instructor makes initial contact with students within the first five days of class. The instructor is expected to reach out beyond email or messages to the mentor and/or guardian by phone if a student has not engaged consistently in the course after the first month of enrollment. |

| 3d: Using Assessment for Learning Elements of Success: • Clear standards for success • Monitoring student understanding • Timely, constructive feedback | D5 The online teacher helps learners reach content mastery through instruction and quality feedback using various formats. The online teacher provides actionable, specific, and timely feedback. | Score and provide feedback on student-submitted assignments within 72 hours (96 hours for ELA and AP courses) of submission, Monday-Friday. Assignments should receive specific, detailed, and individualized feedback. Feedback should include the use of scoring rubrics where available but must also include a comment on areas of strength and/or areas in need of improvement. Individualized feedback is professional, positive, personal, and encouraging. |

Conclusions

During the first four weeks of a course, teachers primarily use BrightSpace, the Student Learning Portal (SLP), and individual emails to communicate with students. Many teachers noted that the SLP is particularly effective, as students must log in to the SLP before accessing Brightspace and their course(s), making messages more visible.

On average, teachers (n = 45) sent about 119 messages—roughly two per student—during this period. In a virtual setting, teachers emphasize the importance of crafting messages that convey a welcoming, compassionate tone to foster positive relationships. Teachers reported strategies such as using tone-checking tools (e.g., Grammarly) and incorporating personalized feedback to create a connection. Best practices for cultivating positive relationships and communicating effectively include:

- Responding promptly to students.

- Using a welcoming tone.

- Consistently providing specific, constructive, and timely feedback to students. Incorporating students’ personal details (e.g., hobbies, first names) can help tailor/personalize feedback to the student.

Students most commonly use the SLP, email, and text messages during the first four weeks of a course. Because students’ communication preferences vary, it is important for teachers to be open and responsive to what seems to work for each student. However, teachers may prioritize communication via the SLP and email, which both parties widely use.

Students typically reach out to clarify course requirements, ask about content, or inquire about grades. Teachers can prepare FAQ documents and resources to streamline responses to address these student concerns. When students ask specific questions, teachers may gently encourage proper pacing, time management, and self-reflection to help students develop these skills because helping students strengthen or establish metacognitive skills can help them succeed with online learning (Xu et al., 2023; Zion et al., 2015). Contacting teachers for emotional or social support was not widely reported in the first four weeks. This may point to the need for consistent and respectful communication over time for building strong teacher-student relationships (Duong et al., 2019; Kincade et al., 2020).

Although a positive relationship was observed between the number of messages sent and student grades, it was not statistically significant. This may be due to the study’s focus on the first four weeks when teachers have limited data to identify struggling students. Additionally, the uniformity in the number of messages sent by teachers may have obscured the relationship between grades and communication. Statistical significance often depends on factors like sample size or variability in the data. Indeed, across all quartiles of grades, students received a similar number of messages from their teachers, and this uniformity may have made it difficult to detect an effect. Michigan Virtual teachers may already be engaging in best practices for communication with their students, and thus, there was not much variation in the number of messages sent across students with differing levels of course performance. In other words, students who would likely be helped by interventions focused on communication are likely already receiving it, thus, leaving little room for improvement.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, the importance of communication for relationship-building remains clear. Teachers should continue using best practices—personalized, timely feedback and communication—as these strategies are supported by research and teacher experience. Found within Michigan Virtual’s professional learning portal, a series of courses specific to online teaching and learning—the content of which was written by Michigan Virtual teachers—focuses on these best practice strategies. The Level 1 series consists of eight courses designed for educators new to online teaching, including Communicating in Online Classrooms and Grading and Feedback. The Level 2 series also consists of eight similar courses but is designed for educators with experience with online teaching and learning. These courses may provide both new and seasoned online teachers with strategies for communicating effectively and building relationships with their online students.

Effective teacher-student communication is crucial in online courses. Teachers should:

- Leverage the SLP and email as primary communication tools.

- Use tone-checking tools and tailor feedback with personal details.

- Prepare FAQs and resources to address common student questions.

- Foster metacognitive skills to aid student success in online learning.

Continued focus on timely and personalized communication should be part of teacher training and professional development during the first weeks and throughout the course. While the study did not find a significant link between communication and grades, the practical importance of communication for building relationships remains vital for student success. Future research should explore the role of student-initiated communication and the reciprocal nature of communication to better understand its impact on academic outcomes. Another consideration for future research is exploring the role of teacher-student communication throughout a course to determine if measuring reciprocal communication for a longer length of time provides a more accurate understanding of its impact on students’ academic outcomes in online courses.

Appendix A

Appendix A: Courses Included in SLP Data

| NCES Subject Area | Course | N Enrollment |

| English Language and Literature | Mythology and Folklore: Legendary | 165 |

| American Literature A – English 11-12 | 59 | |

| American Literature B – English 11-12 | 43 | |

| Life and Physical Sciences | Medical Terminology | 384 |

| Chemistry A | 48 | |

| Chemistry B | 31 | |

| Mathematics | Mathematics of Personal Finance | 229 |

| Mathematics in the Workplace | 145 | |

| Geometry A | 73 | |

| Social Sciences and History | Criminology | 310 |

| Economics | 203 | |

| Civics | 191 |

References

Borup, J., Chambers, C. B., & Stimson, R. (2019). K-12 student perceptions of online teacher and on-site facilitator support in supplemental online courses. Online Learning, 23(4), 253-280.

Brake, A. Right from the Start: Critical Classroom Practices for Building Teacher–Student Trust in the First 10 Weeks of Ninth Grade. Urban Rev 52, 277–298 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-019-00528-z

Brewster, A. B., & Bowen, G. L. (2004). Teacher support and the school engagement of Latino middle and high school students at risk of school failure. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 21, 47-67.

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113-143.

Corry, M., Ianacone, R., & Stella, J. (2014). Understanding online teacher best practices: A thematic analysis to improve learning. E-Learning and Digital media, 11(6), 593-607.

Cuccolo, K. & DeBruler, K. (2024). Out of Order, Out of Reach: Navigating Assignment Sequences for STEM Success. Michigan Virtual. https://michiganvirtual.org/research/publications/out-of-order-out-of-reach-navigating-assignment-sequences-for-stem-success/

Curtis, H., & Werth, L. (2015). Fostering student success and engagement in a K-12 online school. Journal of Online Learning Research, 1(2), 163-190.

DeBruler, K. & Harrington, C. (2024). Key Strategies for Supporting Disengaged and Struggling Students in Virtual Learning Environments. Michigan Virtual. https://michiganvirtual.org/research/publications/key-strategies-for-supporting-disengaged-and-struggling-students-in-virtual-learning-environments/

Duong, M. T., Pullmann, M. D., Buntain-Ricklefs, J., Lee, K., Benjamin, K. S., Nguyen, L., & Cook, C. R. (2019). Brief teacher training improves student behavior and student-teacher relationships in middle school. School Psychology, 34(2), 212.

Freidhoff, J. R., DeBruler, K., Cuccolo, K., & Green, C. (2024). Michigan’s k-12 virtual learning effectiveness report 2022-23. Michigan Virtual. https://michiganvirtual.org/research/publications/michigans-k-12-virtual-learning-effectiveness-report-2022-23/

Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child development, 72(2), 625-638.

Harrington, C. & DeBruler, K. (2021). Key strategies for engaging students in virtual learning environments. Michigan Virtual University. https://michiganvirtual.org/research/publications/key-strategies-for-engaging-students-in-virtual-learning-environments/

Hosler, K. A., & Arend, B. D. (2012). The importance of course design, feedback, and facilitation: Student perceptions of the relationship between teaching presence and cognitive presence. Educational Media International, 49(3), 217-229.

Hwang, N., Kisida, B., & Koedel, C. (2021). A familiar face: Student-teacher rematches and student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 85, 102194.

Heilporn, G., Lakhal, S., & Bélisle, M. (2021). An examination of teachers’ strategies to foster student engagement in blended learning in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18, 1-25.

Jou, Y. T., Mariñas, K. A., & Saflor, C. S. (2022). Assessing cognitive factors of modular distance learning of K-12 students amidst the COVID-19 pandemic towards academic achievements and satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences, 12(7), 200.

Joosten, T., & Cusatis, R. (2019). A Cross-Institutional Study of Instructional Characteristics and Student Outcomes: Are Quality Indicators of Online Courses Able to Predict Student Success?. Online Learning, 23(4), 354-378.

Kincade, L., Cook, C., & Goerdt, A. (2020). Meta-analysis and common practice elements of universal approaches to improving student-teacher relationships. Review of Educational Research, 90(5), 710-748.

Lavy, S., & Naama-Ghanayim, E. (2020). Why care about caring? Linking teachers’ caring and sense of meaning at work with students’ self-esteem, well-being, and school engagement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 91, 103046.

Leitão, N., & Waugh, R. F. (2007). Students’ views of teacher-student relationships in primary school. Annual International Educational Research.

Li, X., Bergin, C., & Olsen, A. A. (2022). Positive teacher-student relationships may lead to better teaching. Learning and Instruction, 80, 101581.

Liu, F., & Cavanaugh, C. (2011). High enrollment course success factors in virtual school: Factors influencing student academic achievement. International Journal on E-learning, 10(4), 393-418.

Martin, A. J., & Collie, R. J. (2019). Teacher-student relationships and students’ engagement in high school: Does the number of negative and positive relationships with teachers matter? Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(5), 861.

Martin, A. J., & Dowson, M. (2009). Interpersonal relationships, motivation, engagement, and achievement: Yields for theory, current issues, and educational practice. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 327-365.

Mensah, B., & Koomson, E. (2020). Linking teacher-student relationship to academic achievement of senior high school students. Social Education Research, 102-108.

Michigan Virtual. (n.d.). Student Guide to Online Learning. Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/resources/guides/student-guide/

Miller, K. E. (2021). A Light in Students’ Lives: K-12 Teachers’ Experiences (Re) Building Caring Relationships During Remote Learning. Online learning, 25(1), 115-134.

Prewett, S. L., Bergin, D. A., & Huang, F. L. (2019). Student and teacher perceptions on student-teacher relationship quality: A middle school perspective. School Psychology International, 40(1), 66-87.

Roblyer, M. D., Davis, L., Mills, S. C., Marshall, J., & Pape, L. (2008). Toward practical procedures for predicting and promoting success in virtual school students. American Journal of Distance Education, 22(2), 90–109.

Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M., Spilt, J. L., & Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher-student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research, 81(4), 493-529.

Straub, E. O. (2024, January 15). Giving good online feedback. University of Michigan. https://onlineteaching.umich.edu/articles/giving-good-online-feedback/

Turley, C., & Graham, C. (2019). Interaction, student satisfaction, and teacher time investment in online high school courses. Journal of Online Learning Research, 5(2), 169-198.

Van Leeuwen, A., & Janssen, J. (2019). A systematic review of teacher guidance during collaborative learning in primary and secondary education. Educational Research Review, 27, 71-89.

Xu, Z., Zhao, Y., Zhang, B., Liew, J., & Kogut, A. (2023). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of self-regulated learning interventions on academic achievement in online and blended environments in K-12 and higher education. Behaviour & Information Technology, 42(16), 2911-2931. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2022.2151935

Zion, M., Adler, I., & Mevarech, Z. (2015). The effect of individual and social metacognitive support on students’ metacognitive performances in an online discussion. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 52(1), 50-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633114568855

Zweig. J. (2023). The first week in an online course: Differences across schools. Michigan Virtual. https://michiganvirtual.org/research/publications/first-weeks-in-an-online-course/