Oxford at a Glance

Location: Oakland County, Michigan

NCES Designation: Suburban: Large

Number of School Buildings: 10

Total Staff (FTE): 727

Classroom Teachers (FTE): 394

Number of Students Served: 5,792

- Empowering Teachers and Capturing Kids’ Hearts®: The Public Schools of Calumet, Laurium, and Keweenaw’s Journey Toward Student-Centered Learning

Programs, Pathways, and Proficiency Scales Anchor Student-Centered Learning at Berrien Springs Public Schools

Introduction

Located approximately 15 miles west of Detroit in the rolling hills of northern Oakland County is one of Michigan’s PreK-12 International Baccalaureate school districts—Oxford Community Schools. The school district consists of five elementary schools (Daniel Axford Elementary, Clear Lake Elementary, Lakeville Elementary, Leonard Elementary, and Oxford Elementary), Oxford Middle School, Oxford High School which includes Oxford Schools Early College, two alternative schools (Oxford Bridges High School and Oxford Crossroads Day School), and Oxford Virtual Academy. Oxford Community Schools serves approximately 5,800 students, 93% of whom are white, and roughly 3% of Oxford students have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) recommending service.

Geographically, it is one of the largest districts in southeastern lower Michigan as it stretches into five townships and two villages. Despite its close proximity to Detroit, Oxford’s quaint downtown gives both locals and visitors a small-town feel. The downtown streets are lined with two- or three-story brick buildings which house restaurants and small businesses. Many of the town’s small businesses have ties to the school district, and as a result, the community is close-knit. A strong sense of community is one of the many things that makes Oxford Community Schools unique. There is an obvious and intentional effort within Oxford to bring the school district and the community together as well as a strong sense of community within the school district itself.

Oxford is driven by a culture of sustained improvement as they strive to ensure all students have access and opportunity as they meet students at their point of need. Their deliberate efforts to make learning student-centered are apparent throughout the district in many ways: an International Baccalaureate program fostering creative thinking and learner agency, a well-developed career and technical education program, an early college program empowering students to take ownership of their education, and a virtual academy customized to meet the needs of individual students. These student-centered programs of Oxford are driven by an empowered staff all rowing together in the same direction and guided by a shared vision for student success.

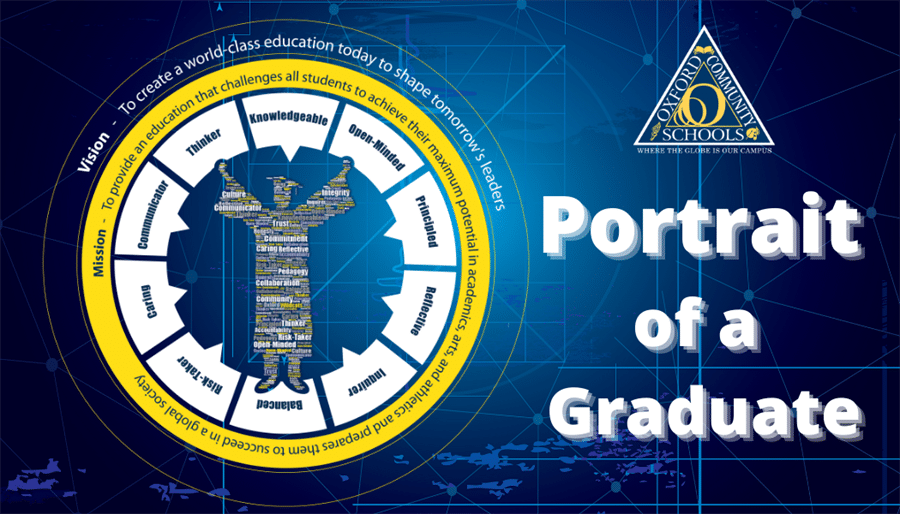

Portrait of a Graduate: A Shared Vision for all Oxford Students

In our 2021 report Student-Centered Learning in Michigan K-12 Schools: Factors that Impact Successful Implementation, the Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute (MVLRI) research team found that one of the key structures that school leaders are putting in place to support teachers in making the shift toward student-centered learning is creating a vision for the district. To be more than the district administration’s vision or just a document that sits on a shelf, it should be developed with stakeholder input. Starting with the end in mind by creating a portrait of a graduate can help educators and school leaders consider what their vision is for learning when it is truly student-centered. It is something that can help to steer the ship, ensuring that districts stay the course and remain focused on the characteristics and competencies they believe are most important for students to acquire.

Developed with community input and stakeholder involvement, Oxford’s Portrait of a Graduate articulates their shared vision for all graduates as a result of their educational experiences in Oxford Community Schools. The Portrait of a Graduate outlines the characteristics (based on traits found in the International Baccalaureate Learning Profile), the competencies (skills required to be a productive citizen) they believe are necessary for all students to be successful, and the conditions for learning they envision will allow each student to develop to his or her potential. Completed in 2019, it took about a year and a half to develop as input was gathered from stakeholder surveys, literature on educational trends and 21st-century learning, data generated from the school district, requirements of the Michigan Merit Curriculum, principles and practices of the International Baccalaureate Programme, and processes used to identify future employment opportunities and student career aspirations.

It is evident Oxford’s Portrait of a Graduate is not just something superficial they have created, it represents what they believe in. As Ken Weaver, Oxford Community Schools superintendent explained: “Our Portrait of a Graduate speaks to the whole child. It speaks to every facet that each child comes to us with as well as those they don’t that we will help them develop.” It is a summary of the work they are doing and represents their shared vision. The Portrait of a Graduate is visible everywhere throughout the school district, driving many of the decisions they make and serving as a constant reminder of their student-centered mentality. Assistant Superintendent of Elementary Instruction Anita Qonja-Collins believes that the Portrait of a Graduate is about making connections between district initiatives and the fact that students are at the heart of their work. “The student is at the center of all of it,” stressed Qonja-Collins.

“Our Portrait of a Graduate speaks to the whole child. It speaks to every facet that each child comes to us with as well as those they don’t that we will help them develop.”

Ken Weaver, Oxford Community Schools superintendent

International Baccalaureate Programme: Where the Globe is our Campus

Because the characteristics outlined in Oxford’s Portrait of a Graduate are based on attributes in the International Baccalaureate learner profile, there is obvious cohesion between the International Baccalaureate (IB) Programme and the district’s shared vision for their students. The IB Programme is a big part of who Oxford is as a district as all traditional Oxford students receive IB instruction in grades PreK-10 with the exception of students attending Oxford Virtual Academy, Bridges Alternative High School, and Crossroads Day School, as these programs are not IB authorized. The IB Programme serves as a curriculum framework that is balanced and appropriate to every student’s age while offering a holistic approach to meeting the intellectual, social, and emotional needs of all Oxford students. The Programme is cross-curricular and student-centered in its nature as students are empowered to take ownership of their learning and are encouraged to become active, compassionate, and lifelong learners. Former Oxford Community Schools Superintendent Tim Throne explained that “In the last 6-10 years, our IB programs have strived to implement voice and choice for our traditional students. The way that we deliver our IB units and core content…a lot of that curriculum is written around different themes that are driven by student voice. Students have direction in terms of what they learn and what they present on. And once they get to the secondary level, they have choices in terms of classes that they want to take.”

Throne, who worked in the district from 2000-2022 and served as superintendent from 2015-2022, noted that in order to become an International Baccalaureate school district, their teachers had to go through rigorous training and periodic recertification. Because the IB framework only serves to guide instruction and does not come with any prescribed curriculum, it is their teachers who are developing the content for their courses. Throne acknowledged that “At the end of the day, it’s costly. But at the same time, it’s our curriculum. Our people are writing it. They own it, and I think we are finally starting to get returns on our investment.” Not only does the IB Programme provide voice and choice for students, but because teachers are writing the curriculum to go along with the IB framework, teachers also have voice, choice, and a sense of autonomy.

“The way that we deliver our IB units and core content…a lot of that curriculum is written around different themes that are driven by student voice. Students have direction in terms of what they learn and what they present on.”

Tim Throne, former Oxford Community Schools superintendent

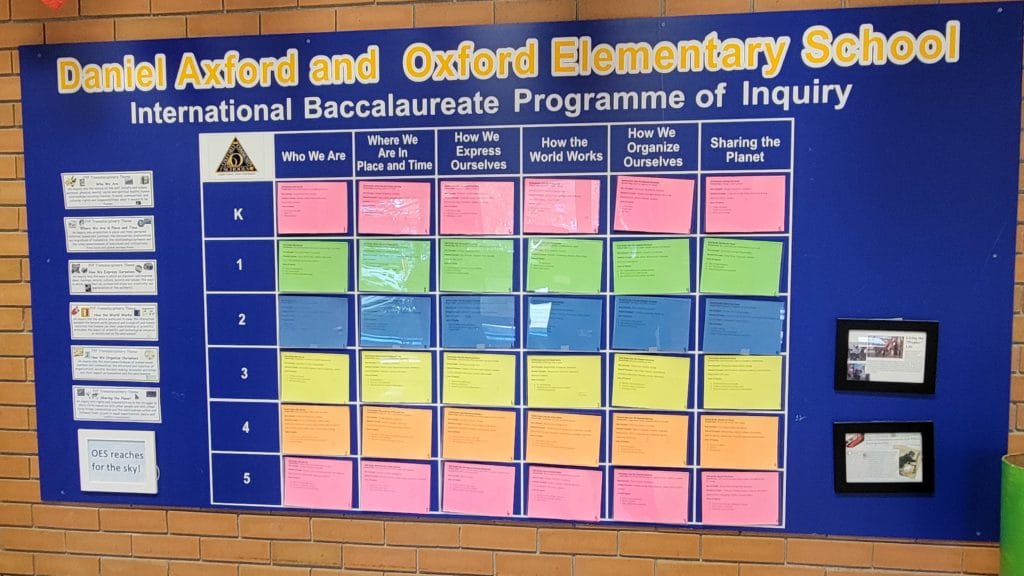

Primary Years Programme: Agents of their Own Learning, Partners in the Learning Process

At the elementary level, all traditional PreK-5 Oxford students participate in the Primary Years Programme (PYP), which is organized into six themes: who we are, where we are in place and time, how we express ourselves, how the world works, how we organize ourselves, and sharing the planet. Each grade level has its own central idea, growing in complexity from Pre-K through fifth grade, for each of the six transdisciplinary themes (curriculum revolves around real-world experiences without regard for discipline-specific understandings). The central ideas that each grade level has developed help teachers connect the IB themes to their curriculum and guide their instruction. The central ideas also serve as “big life lessons” for students as teachers connect them and the six IB themes to all subject areas. As Courtney Morin, the IB coordinator for both Daniel Axford Elementary and Oxford Elementary, clarified: “We look at what we are teaching in math, reading, writing, and science during each six weeks under each of these themes so that we can highlight them for our learners to also teach them about life.” In addition to developing an international mindset, teaching students how to learn and how learning connects to real-life are some of the main goals of the IB Programme.

As the MVLRI research team observed during classroom site visits, learning is very student-centered within the PYP. Students have voice and choice as they participate in decision-making and engage with multiple perspectives while developing an understanding of how they learn best. Students develop agency and ownership of their learning as they co-construct and reflect upon their learning goals and are provided with choices in their academic work in terms of projects, assessments, partners, and what they read.

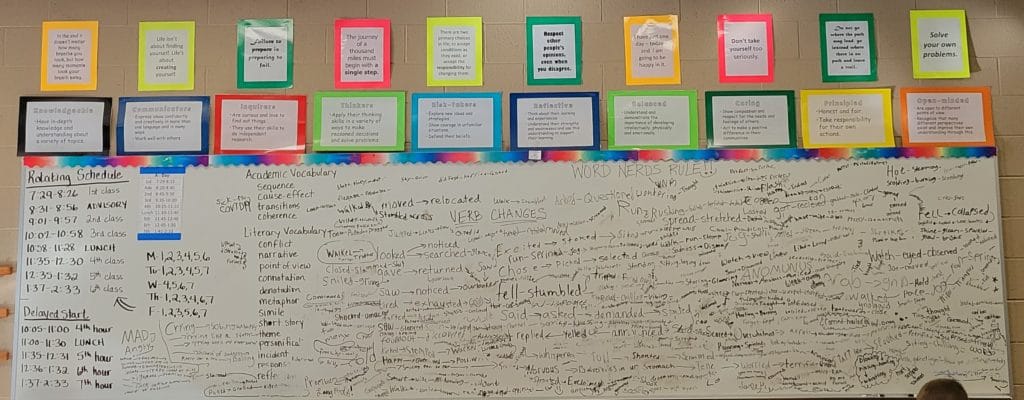

During one lesson in particular, students sat together at the front of the room in different choice-based seating configurations: on the carpet, upside-down buckets with cushions fashioned for a seat, step stools, and in chairs. Through whole group and partner discussion, students identified character traits and themes from a book the class previously read. Students were encouraged to think deeply about the story—about the characters, their motives, and possible themes. This particular lesson was also part of a writer’s workshop activity built around proficiency scales. The class analyzed what it looked like to discuss and write about various themes using evidence to support their thinking and were given examples of what this would look like on a 1 (limited mastery of skill/standard), 2 (partial mastery), or 3 (on track to mastery) proficiency scale. In addition to this particular activity providing a pathway for students to understand how to earn their scores, it was evident that there were many established routines as the lesson moved almost effortlessly between students turning and talking with a partner and having whole group discussions. Students were encouraged to, and felt very comfortable, sharing their ideas with the class.

The STEM and robotics classroom at Oxford Elementary, a new program as of the 2021-22 school year, is another way that students are provided with student-centered learning opportunities within the PYP. The classroom is bright and colorful, filled with wobble stools for student seating, tables that are easy to move and adjust, and a full set of iPads. Students learn how to code and see their coding skills brought to life through Dash the robot. Through resources from Oxford’s career and technical education program, much of the furniture and equipment have been funded for them. In addition to the STEM and robotics classroom, a STEMi truck funded by the Oakland County ISD travels around to all schools within Oakland County. The STEMi mobile innovation lab, which launched in the spring of 2021, is brimming with different STEM activities aimed at engaging K-12 learners such as virtual reality goggles, collaborative robots, and autonomous vehicles that students learn how to code. Through both the STEM and robotics classroom and the STEMi, students will be better prepared for STEM opportunities at the middle and high school as well as build career awareness through these hands-on, student-centered learning experiences.

The Primary Years Programme culminates in 5th grade with an exhibition project. This project, and the work leading up to it, gives students the chance to exemplify the attributes of the IB learner profile, demonstrate knowledge and skills they have learned, and to have a voice in making a difference in their community. The exhibition project is very student-driven as students choose their own project based on a topic that is meaningful to them. Scaffolding and preparation take place throughout the years in the PYP to get students ready for this event and the work required of it. The actual exhibition event is a showcase of student work where both students and parents get to see many different forms of learning. Oxford Elementary School principal Jeff Brown described how a previous group of students investigated different types of cancer for their exhibition project. As part of the “student-generated action” component of their project, the students created tee shirts inviting others to ask them about their project and wore them around their local Meijer. As Brown explained, “This was their plan of how they wanted to share their learning with the world: choosing their own topic, doing the research, figuring out how they want to present it, and then actually doing something about it as a result.”

Giving students voice and choice—the opportunity to choose to learn the way they learn best and to direct some aspects of their learning—helps to make students feel personally invested in their learning. It gives them a role in shaping and creating it, resulting in higher levels of student engagement, empowerment, and hopefully achievement. Brown stressed that the skills students develop during the PYP are skills that will not only better prepare them for middle and high school, but also for life: “Communication skills, research skills—those are all of the approaches to learning that we keep coming back to because those are the skills that are really going to matter when they graduate from our K12 program and go out into the real world.”

“This was their plan of how they wanted to share their learning with the world: choosing their own topic, doing the research, figuring out how they want to present it, and then actually doing something about it as a result.”

Jeff Brown, Oxford Elementary School principal

Middle Years Programme: Connecting Learning to Real-Life

Similar to students participating in the Primary Years Programme, all traditional Oxford students in grades 6-10 participate in the Middle Years Programme (MYP). The MYP builds upon the knowledge and skills students develop during the PYP while highlighting intellectual challenge, communication, intercultural understanding, and global engagement—encouraging students to make connections between what they are learning in the classroom and the world around them. The MYP consists of eight subject groups: language acquisition, language and literature, individuals and societies, sciences, mathematics, arts, physical and health education, and design. Within the curriculum, emphasis is placed on learning experiences that have context and are connected to students’ lives, big ideas and conceptual understandings, approaches to learning that can help students apply knowledge and skills in unfamiliar contexts, community service, and learning to communicate in a variety of ways. Interdisciplinary learning—integrating knowledge and skills from two or more subject areas—is a big part of the MYP. Students in the Middle Years Programme complete at least one collaboratively planned interdisciplinary unit each year.

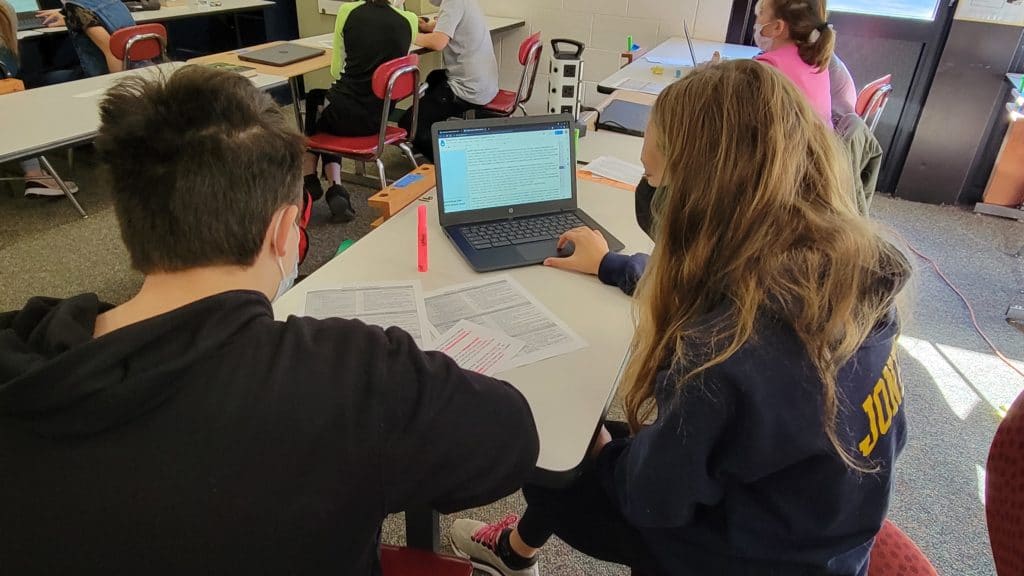

Learning within the MYP is very student-centered at Oxford Middle School and Oxford High School. As the MVLRI research team walked through hallways and visited classrooms, evidence of the commitment to Oxford’s Portrait of a Graduate and the IB learner profile can be seen everywhere. In Neil Peruski’s 6th grade English language arts classroom (language and literature MYP subject group), students demonstrated agency and ownership as they used a rubric to help revise each other’s choice-based personal narrative writing. Rather than a teacher leading the conversation and providing revision suggestions for students, students were leading and driving this peer revision work. A large whiteboard in the classroom served as a “word wall,” encouraging students to consider replacing bland language with more interesting words or phrases. This whiteboard was student-driven, filled with their ideas and contributions, and emphasized that students had a voice and were shaping the learning.

In Ms. House’s Introduction to Spanish class (language acquisition), flags from different Spanish speaking countries hung from the ceiling, tissue paper flags called papel picado were displayed on the walls, and books to introduce students to different cultures and customs from Spanish speaking countries lined the cabinets and ledges throughout the room. Students moved around the classroom with a partner completing a looping activity to practice translating English words to Spanish and vice versa. Incorporating movement into the lesson format encouraged even reluctant learners to become engaged in the learning process.

Eighth-grade students in Taylor LaMagna’s math class explained their thinking and demonstrated their approach to solving math problems in their own words. Vertical whiteboards hung from the walls around the room which allowed students to explain their thinking in a more visible way—not only with their teacher but with their peers as well. On their Chromebooks (all Oxford students have a dedicated personal computing device), students used Quizlet Live to solve math problems individually while contributing to their team’s score. Through competition and collaboration, Ms. LaMagna has increased student engagement. As LaMagna noted, math class tends to be very structured and teacher-directed in terms of presenting the lesson, the notes, and the homework assignment. In order to make learning student-centered in her math classroom, LaMagna strives to help students make personal and real-world connections to what it is they are learning and to increase engagement. “A huge part of that for me, being able to do that here at Oxford, is we are one-to-one. So the technology and programs that we have available for us to use in the classrooms helps a great deal,” LaMagna admitted. She elaborated, explaining that for students who don’t understand slope or how it can be represented, she makes connections to something that can be represented in multiple ways. She described an activity in which students used Nearpod to explore a virtual reality 3D version of New York City and identified where they saw slopes throughout the city. LaMagna believes that making these connections between what they are learning in the classroom to the real world (a critical part of the MYP and Oxford’s Portrait of a Graduate) really helps students who may struggle to grasp the concept the first time around.

“A huge part of that for me [making real-world connections to learning], being able to do that here at Oxford, is we are one-to-one. So the technology and programs that we have available for us to use in the classrooms helps a great deal.”

Taylor LaMagna, Oxford Middle School math teacher

As part of the MYP design subject group and as a way to encourage students to make connections between what they are learning in the classroom and the world around them, 6th and 7th-grade students at Oxford Middle School (OMS) take Project Lead the Way® (PLTW) courses. PLTW® is an innovative engineering program that addresses the interests of middle school students while incorporating math, science, and technology standards. PLTW® is “activity-oriented” to show students how technology is used in engineering to solve everyday problems. Eighth-grade students can continue to take PLTW® courses or they can choose to take Introduction to Computer Programming, Newspaper, or Yearbook. OMS students also have the opportunity to participate on a robotics team. Participation on the robotics team as well as engineering and technology courses like PLTW® and Introduction to Computer Programming can be continued throughout high school for Oxford students. At Oxford High School (OHS), students can participate on the robotics team (Team 2137) and/or pursue an engineering pathway through their career and technical education program.

In their final year of the MYP (10th grade), some OHS students explore an area of personal interest over an extended period called the personal project. The personal project is student-centered, designed to be completed independently, and is an opportunity for students to demonstrate what they have learned throughout grades 6-10. There are three elements that students must complete: product or outcome—evidence of tangible or intangible results (what the student was aiming to achieve or create); process journal—ideas, criteria, developments, challenges, plans, research, possible solutions, and progress reports; and a report—an account of the project and its impact, including a bibliography and evidence from the process journal that documents students’ development and achievements. In order to complete the personal project, students must utilize the self-management, research, communication, critical and creative thinking, and collaboration skills they have learned in the MYP.

Diploma Programme: Preparing Students to Become Active Participants in a Global Society

Upon completion of the Middle Years Programme, Oxford students in 11th and 12th grade can choose to pursue the Diploma Programme (DP). The DP curriculum is made up of six subject groups—language acquisition, studies in language and literature, individuals and societies, mathematics, sciences, and the arts—as well as the DP core, which requires students to reflect on the nature of knowledge, complete independent research, and undertake a project that usually involves community service. The PYP, MYP, and DP are all philosophically aligned, each centering on developing within students the attributes of the IB learner profile, which are the characteristics found in Oxford’s Portrait of a Graduate.

To complete the Diploma Programme, students must write both a theory of knowledge essay as well as an extended essay. The theory of knowledge essay asks students to reflect on the nature of knowledge and on how to know what we claim to know. It is assessed through an oral presentation as well as a 1,600-word essay. The extended essay, which is also mandatory for all DP students, is an independent, self-directed piece of research resulting in a 4,000-word paper. Because the extended essay is self-directed, DP students have voice and choice in terms of their topic selection, how they develop their research question and argument, and how they communicate their ideas. An Oxford Diploma Programme student excitedly explained how the extended essay can be about anything you want, so “no two students are doing the same thing.” It does, however, need to fit into a subject like history, science, or math, and students are required to get guidance from a teacher in their research paper’s respective subject.

Evidence of student-centered learning is found not only within the structure of the Diploma Programme but within the courses themselves. There are many courses students are required to take, which only leaves two elective slots for non-IB courses over DP students’ junior and senior years, which can be limiting. However, as one Oxford DP student remarked: “Within the IB classes, there’s definitely a lot of choice.” They shared that it is often students who are leading and driving group discussions rather than the teacher, which students find very engaging. And when completing projects, teachers provide many avenues for choice, especially when it comes to the topic. Another Oxford DP student stressed how much they appreciated the ability to write about topics that interest them, even topics that may not be typically covered in traditional curriculum: “Having options definitely allows students to get more invested into their work and actually learn more, as opposed to just the content regurgitation that you get from other more traditional classes. Having choices on the larger assignments really helps me get more personally invested because I’ve chosen the topic.” Despite the challenging coursework, it was clear that Oxford’s Diploma Programme students find that having a choice of learning about what interests them results in increased student engagement.

High School Pathways: Opportunities Only Found in Oxford

An abundance of windows greeted the MVLRI research team as they walked up to Oxford High School. Natural light streamed into the school’s main entrance, main office, and atrium where they later sat and talked with a group of students over lunch. These students were very talkative and eager to share about the different pathways and programs in which they are involved because of the opportunities available throughout the school district.

Oxford Schools Early College (OSEC) is one of the pathways that students were excited to discuss. During OSEC’s 5-year program, students engage in both high school and college at the same time. Within the program, OSEC students earn transferable college credits, potentially up to an Associate’s Degree, from Macomb Community College, Mott Community College, Rochester University, or Washtenaw Community College before graduating with their high school diploma. Oxford Schools Early College offers both online and face-to-face instruction to empower students to take ownership of the format of their education.

All early college students take a college preparatory course during their first year in the program, but as one OSEC student explained, “From there, you can pretty much branch off into any path that you choose based on what fits your interests and your needs best. OSEC is basically centered around students having choices.” This student went on to describe how the early college program is a great way to take classes based on their interests before actually going to college and declaring a major: “OSEC really allows you to get that college experience but not in a college setting. So you get to test the waters to truly see what you like. I like how it’s pretty much open-ended for you to pick your interests and follow them.”

Another OSEC student remarked how they find the smaller ratio between early college students and their counselors to be very beneficial in terms of being able to discuss future planning or any concerns they may have. They added that the early college mentors really get to know their students because thanks to weekly digital mentor messages, “you’re in constant communication with them.” Because OSEC mentors have their own classrooms, students have a quiet place to complete their online coursework as well as the ability to meet with a mentor pretty much anytime as opposed to a traditional high school mentor who will have classes throughout the day, limiting their availability. As a result, early college students find that mentors and counselors are approachable and available. As one OSEC student added: “It’s nice having those people who are constantly available when you need them.”

“You can pretty much branch off into any path that you choose based on what fits your interests and your needs best. OSEC is basically centered around students having choices.”

Oxford Schools Early College student

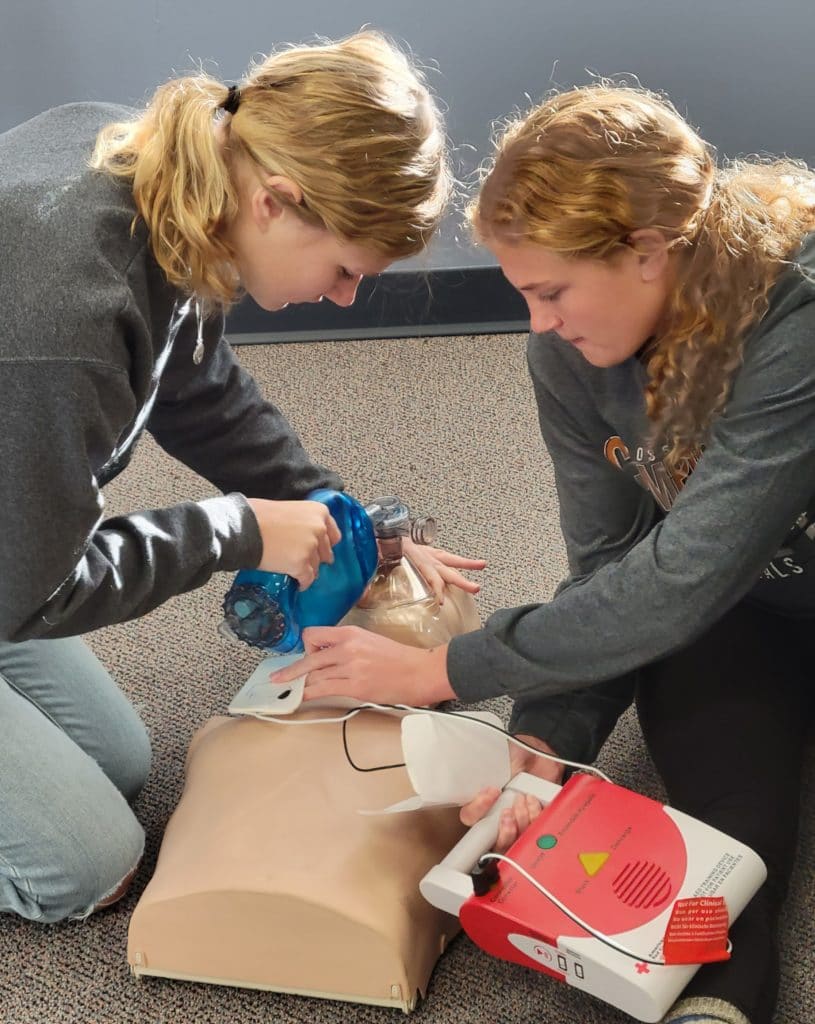

Oxford’s career and technical education (CTE) program is another student-centered pathway available to high school students. Oxford Community Schools actually boasts the second-largest CTE program in Michigan, offering 10 different state-approved programs. They are state-funded and designed around the demonstration of competencies that are laid out by the Michigan Department of Education. Within the Health Science CTE program, seniors have the option to take a 2-credit EMT block. This additional EMT pathway (added as of the 2020-21 school year) grew from a need for EMTs within the Oxford Community and is attributed to the close relationship between the community and the school district. Students who choose to participate in this EMT pathway spend first and second periods at the Oxford Fire Department (OXFD) as well as complete clinical hours outside of the school day. During the MVLRI research team’s visit to the OXFD, they observed students working in pairs as they practiced giving CPR and pressurizing oxygen tanks. Within this pathway, students learn real-life skills that they will be required to demonstrate and apply if they work in the field while learning from actual practitioners. Upon successful completion, students are eligible to take the EMT exam in order to become certified emergency medical technicians. In fact, two Oxford students who went through this program now work at the Oxford Fire Department as EMTs. Demonstrating mastery of skills or competencies through participation in this program significantly increases students’ likelihood of employability.

Oxford’s Auto Mechanics CTE program is designed to prepare students in grades 9-12 for a career in the area of automotive technology. Just like in the EMT program, students learn from instructors that have experience in the field. In fact, CTE instructors must have at least 4,000 hours of industry experience in order to be certified to teach. Students split their time between classroom-based learning and hands-on learning on the shop floor. During the MVLRI research team’s visit, the auto shop was noisy and busy as students checked brakes, used diagnostic testing equipment, and implemented shop practices with cars donated either by the Oxford community or by General Motors. In order to participate in the program and handle equipment, students must be safety certified. And after their third year, students pursuing an ASE certification sit for their state certification exam.

Oftentimes, seniors have the opportunity to take part in a work-based placement program in which they may be paid for their work and also receive credit for the experience as long as the experience matches their Educational Development Plan (EDP). As CTE coordinator Lisa Butts acknowledged, “While work-based learning experiences are required by the state of Michigan for all CTE students, we are not only giving students opportunities for field trips and speakers but also putting them in real-life situations.” For some students, it is the hands-on, student-centered, real-life experience that they gain from this program as well as others that keep them engaged and coming to school.

Both the Mechatronics and Engineering CTE programs provide students with opportunities to explore their interests in robotics and engineering. For some students, these programs also serve as a continuation of interests developed during elementary school STEM experiences and/or middle school Project Lead the WayⓇ courses. Craig Trombly, who teaches the four courses that comprise the Mechatronics program, recognizes this and knows that his classes are filled with a wide range of student abilities in terms of computer-assisted design (CAD). Therefore, he knows his students need to be able to move through courses and master competencies at their own pace, sorting out their own individual paths. Because students are at different levels and work at different paces, Mr. Trombly explains assignments at the beginning of class and then circulates the classroom to help guide and assist students as needed. As Trombly described: “Everybody’s learning at their own pace. So I’ve got to try to meet them where they are and help them move forward.”

Looking at these programs through the lens of student-centered learning and listening to empowered learners share what having voice and choice means to them shines a light on the work of Oxford teachers and school leaders. Students shared that many of their projects are open-ended. While projects usually contain some requirements, students described having creative control as to what they design, create, and research. As a CTE student acknowledged: “It’s a lot more exciting when you can make what you want to make and do it by yourself rather than going with the class. It’s also really cool to see what everyone makes because everyone’s going to end up with something different.” Not only does having voice and choice allow students to express their own creativity and recognize it in others, having the ability to work at their own pace alleviates some pressure, admitted another student: “It’s nice that you don’t have to work at everyone else’s pace if you don’t fully understand something. You can take a whole class period instead of a half-hour to work on something if you need to.” This student added that they believe the ability to work at their own pace leads to more meaningful learning.

Within these different pathways available to Oxford High School students, learning is personalized and tailored towards students’ interests. While all Michigan students are required to have an EDP, Oxford firmly believes that an EDP is not just a document that students simply fill out and ignore. Steve Wolf, Oxford High School principal, stressed that it’s something staff use to help students plan and explore career options; it’s something that is revisited often: “They [students] look at their interests and their career aspirations and align that to what we offer within the district to identify what programs they want to go into and what pathways they want to take while they’re in high school.” Wolf acknowledged that offering so many different options for students does affect the master schedule as students come on and off-campus from other locations throughout the day. However, these opportunities that complicate scheduling also encourage students to become self-directed learners and to expand their learning beyond the walls of Oxford High School. They are precisely what creates empowered learners. The programs not only provide student-centered learning opportunities, but help to develop and nurture within students the characteristics found in both the IB learner profile and Oxford’s Portrait of a Graduate. Oxford students are encouraged to be risk-takers, inquirers, and open-minded. Oxford students are encouraged to be reflective learners, effective communicators, and knowledgeable and principled global-minded individuals. Oxford’s Portrait of a Graduate is visible throughout the district, committed to by staff, and their students are evidence of what both the school district and the community value.

“Everybody’s learning at their own pace. So I’ve got to try to meet them where they are and help them move forward.”

Craig Trombly, Oxford High School Mechatronics teacher

Oxford Virtual Academy: Meeting the Needs of Individual Students

After a short drive down Main Street, the MVLRI research team arrived at Oxford Virtual Academy. Oxford Virtual Academy (OVA) has been offering student-centered educational solutions for students and their families outside of the traditional brick-and-mortar classroom for over a decade. While students can choose to take virtual courses part- or full-time, their drop-in learning centers (K-5 and 6-12) serve as a structured place for students to work or to get specialized one-on-one help from a teacher, tutor, or counselor.

The drop-in centers also provide OVA students with the ability to build relationships with their teachers as well as socialize and develop relationships with their peers. As OVA principal Janet Schell shared: “We try to provide different opportunities to bring students together, to collaborate, and just to get to know each other. If you don’t ever come in, you don’t connect other than Zoom. So we want students to come in as much as possible.” Approximately 30% of their fully virtual students come into the drop-in centers at some point throughout the year. A variety of seating options are available for students including tables, individual workstations, and comfortable couches so they can work individually, with peers, or with a teacher or tutor.

Additionally, the OVA facilities offer a space for students to learn hands-on. During the research team’s visit, one student was working on a project related to his passion for music. He was learning how to electronically program a drum sequence through a digital interface to play in time with the music. The OVA facility provided him with the space and equipment to explore his passion for music as adults helped him troubleshoot issues and served as a sounding board for the learning process.

“We try to provide different opportunities to bring students together, to collaborate, and just to get to know each other. If you don’t ever come in, you don’t connect other than Zoom. So we want students to come in as much as possible.”

Janet Schell, Oxford Virtual Academy principal

In addition to their part- and full-time virtual options, Oxford Virtual Academy has a hybrid pathway that combines in-person, online, and at-home learning for students. The hybrid pathway is teacher mentored and parent facilitated, blending homeschooling and the most attractive aspects of traditional face-to-face education. With an increase in homeschooling due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the hybrid program has continued to grow leaps and bounds. As of the 2021-22 school year, enrollment is approximately 600 students throughout the two hybrid programs in Oxford—Oxford Hybrid Primary and Oxford Hybrid Secondary—as well as several satellite locations throughout southeastern Michigan (Brighton, Farmington Hills, Grand Blanc, Hillsdale, and Shelby Township).

Many OVA hybrid students spend two days each week learning in person at one of the hybrid campus locations and 3 days at home with a curriculum that is approved by the Oxford Community Schools Board of Education. The hybrid program is made up of elective coursework that students can opt into, and smaller class sizes increase the opportunity for student-driven learning guided by interest and engagement. In addition, assessments are often shaped by student choice—how students choose to demonstrate their understanding of the content.

Jordan Dennis, OVA assistant principal and former hybrid learning coordinator, noted that this hybrid program is not only student-centered, but parent- and community-centered as parent choice and community desire played a significant role in creating and shaping the hybrid learning program. Dennis admitted that it came to fruition purely based on parent input and community buy-in: “They [homeschool families] wanted a flexible schedule. They didn’t want to be in a traditional public school classroom and fully online education wasn’t cutting it for them. They wanted more support. They wanted some classroom experience, some hands-on things. Our hybrid program is giving them the resources that they want and need.”

A flexible virtual program like OVA can be a great option for those students who struggle to balance school with other obligations like work or sports, which may require a time commitment that conflicts with the schedule of a typical school day and/or requires significant travel. In fact, some OVA students are actors or are on traveling sports teams. While OVA’s virtual courses offer students flexibility regarding when and where they want to learn, this does require students to take ownership of their learning and to have (or develop) learner agency, a key component of student-centered learning. Staff recognize this and work collaboratively to ensure students are given the support they need to do so. Ryan Moore, one of OVA’s four counselors, explained that counselors work closely with mentors to tie everything together for students. Mentors serve as academic advisors and liaisons between students and teachers, while counselors focus on students’ mental health, scheduling, future planning, personal social development, and career development.

While multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) exist throughout all of Oxford’s buildings, OVA believes their focus on MTSS needs to be more data-driven and intentional because of their virtual environment and the different needs of their students—for example, a traditional student needing preferential seating versus a virtual student needing help to establish effective communication or maintain progress and pace within courses. OVA also has two different software services (GoGuardian and Gaggle) to monitor student activity, flag inappropriate activity, and promote a healthy and safe environment for students. Together, administrators and staff work diligently to ensure internal communication is both efficient and effective to best meet the needs of their students. OVA also has all of the wraparound services that a traditional school building would have to support students such as a social worker, special education instructor, counselor, mentor, learning coach, etc. Through careful monitoring of student data, OVA staff are meeting students’ academic and non-academic needs.

From what the MVLRI research team observed during their visit and the conversations they had with empowered students and impassioned staff, to say that Oxford Virtual Academy is student-centered would be an understatement. OVA students excitedly shared that their teachers often offer different ways to approach the same assignment or even encourage students to come up with their own ideas. A student described how they took one of their teacher’s final project ideas and adjusted it to better fit their interests: “She wanted me to write about the time capsule that I would make, but I wanted to actually make it. She was all on board with my idea. Whatever you want to do, teachers are on board with it, always. It’s not just about what the teachers want you to do.” Students clearly have voice and choice in shaping their learning.

OVA students acknowledged that their teachers are consistently doing exciting things to keep them engaged and motivated throughout the year such as designing STEAM week, offering lunch groups and optional Zoom sessions, holiday celebrations, and virtual field trips. A senior, who has been at OVA since 7th grade, said they find teachers easy to reach out to when they need help and explained that they always respond in a timely manner. Another student added: “And even if it takes all day, they will help you. They always manage to help in some way.” Staff work hard to not only make learning engaging, but to meet students where they are.

Additionally, OVA has developed partnerships within the Oxford community to offer personalized learning opportunities for students while meeting their unique needs through OVA’s optional community-based learning experiences. Through these community partnerships, businesses throughout Oxford host students throughout the week and help with student programming, offering interest-based experiences related to photography, karate, equestrian studies, and art among many others. Students may also take advantage of internship opportunities within some of these partnerships. OVA’s intentional efforts to engage and connect with the community to provide these personalized experiences for students reinforce that Oxford’s Portrait of a Graduate is not just OVA’s vision for their students, it is the community’s vision for student learning. It is a vision that was established with and that continues to be developed in partnership with the community. OVA students are encouraged to embody the characteristics that make up the learner profile, and Oxford Virtual Academy is truly designed to meet the needs of individual students.

“She wanted me to write about the time capsule that I would make, but I wanted to actually make it. She was all on board with my idea. Whatever you want to do, teachers are on board with it, always. It’s not just about what the teachers want you to do.”

Oxford Virtual Academy student

The Power of “Team O”

It is obvious that a strong collaborative culture exists among the staff of Oxford Community Schools. This culture was developed over time and is built upon their shared vision for all Oxford students as a result of their educational experiences—their Portrait of a Graduate. The 10 characteristics that make up the Portrait of a Graduate, which are also the attributes that make up the International Baccalaureate learner profile, affirm a sense of intentional alignment that exists within the district. They strive to develop learners that are balanced, communicators, inquirers, principled, thinkers, reflective, knowledgeable, caring, open-minded, and risk-takers. As OVA counselor Ryan Moore reflected: “We want every kid to understand why they’re in school based on what they see for themselves as in the future, who they see themselves as in the future.”

Oxford staff want every student to imagine themselves pursuing particular paths as an adult, and to try out some of those paths, because that often fuels their idea of themselves as a learner and drives them to become invested in their learning. To do this, Oxford has developed a vision for learning that is student-centered. Students’ needs—both academic and non-academic—are continuously monitored. Students have voice and choice and are encouraged to take ownership of their learning. Learning is personalized, happens anytime and everywhere, and is becoming increasingly competency-based. Mechatronics teacher Craig Trombly admitted: “It’s organized chaos at times, taking their ideas and interests into consideration. However, I feel that ultimately, my job is to let kids be awesome and find what lights their fire.” At Oxford, they are doing exactly that.

“It’s organized chaos at times, taking their ideas and interests into consideration. However, I feel that ultimately, my job is to let kids be awesome and find what lights their fire.”

Craig Trombly, Oxford High School Mechatronics teacher

What Oxford values and wants for their learners is built upon what they value as educators. There is a strong sense of community and culture that exists among them. They refer to it simply as “Team O.” As Janet Schell explained, many staff members live in and/or have children in the community, “so when I’m dealing with a student, it’s not just someone’s child, it’s my colleague’s child.” Schell feels that this gives Oxford a family and community-oriented vibe. There is also a culture of collaboration and innovative thinking. “I can absolutely say that one of the joys of working for this district is the collaborative and innovative vibe. It’s apparent right when you start working here,” proclaimed Moore. He added that this collaborative and innovative vibe is not only for students, but for staff who want to try something new or who have an idea they want to implement with students. OVA hybrid learning coordinator Tracey Hurford shared that she sometimes has difficulty being innovative and taking risks; however, within Oxford, she feels it is encouraged to be a risk-taker and to just “grab the shovel and start digging.” She and others added that part of their “Team O” culture is the professional trust that they are extended, knowing that even if their idea doesn’t work out, they have the freedom and support to try something new.

The Oxford School District’s culture of professional trust has led to an emphasis being placed on identifying personal passions and empowering teachers. Professional development (PD) is a big part of the culture at Oxford, particularly professional development that is designed by staff for staff. For example, an instructional leadership team made up of Oxford Middle School staff meets regularly with administrators to not only plan professional development, but to deliver it. Whether it is through a conversation or a survey, Oxford’s administrators and instructional coaches consistently ask what topics they are interested in exploring and what content would benefit them the most. Oxford Virtual Academy instructional coach Karen Brown knows it would be foolish to think that one person could be the bearer of all information to be delivered to everyone else when they have so many knowledgeable staff members to lean on. Brown described the optional PD groups that OVA is establishing this year: “There’s choice, there’s ownership, and there’s so much excitement because it’s not about how someone’s going to sit there and tell you what to do. It’s about how we’re going to create it and what we are going to come up with. We are deciding what we are looking for, what our questions are, and where we want to go with it.”

Oxford Elementary teacher Rachel Hart noted that they have a similar process at the elementary level in terms of including teachers in the development of PD: “Just last Monday, we had an amazing elementary PD with several different choices. You designed your own day in terms of where you wanted to go, what you needed to see. It was led by staff members, and we even ended the day with optional yoga to restore ourselves. We were able to offer our feedback and then spend our time doing what we need.” Gone are the days of a set PD calendar; Oxford’s professional development is designed based on what staff need in the moment in response to what students need. Adults learn best when they are passionate about what it is they are learning—it is student-centered learning for adults. By experiencing it for themselves, teachers may be more apt to want to replicate it in their own classroom.

“There’s choice, there’s ownership, and there’s so much excitement, because it’s not about how someone’s going to sit there and tell you what to do. It’s about how we’re going to create it and what we are going to come up with. We are deciding what we are looking for, what our questions are, and where we want to go with it.”

Karen Brown, Oxford Virtual Academy instructional coach

“Team O” is built on a culture of sustained improvement. Oxford is committed to making sure their programs are the best they can be for kids and are always looking to add new programs or build new partnerships based on what students want. Former Oxford Community Schools superintendent Tim Throne stressed that “the only way you can become your best is to learn and get better. And so that’s pretty much expected of everybody, independent of your position title. This has helped ingrain an expectation as to how we want to work and play every day.”

Many schools have a portrait of a graduate, but in Oxford, it is everywhere: it is talked about, committed to, and visible in classrooms and in hallways. It is the essence of their goal and their mission. Teachers know they are trusted and empowered with the support of their administration to take risks in order to instill within Oxford students the characteristics of the Portrait of a Graduate—and to make learning student-centered.