Acknowledgements

We would like to thank several partners who helped us complete our study: SEL consultant Lauren Kazee, Paul Liabenow and Taryn Hurley from the Michigan Elementary and Middle School Principals Association (MEMSPA), and Emily Mohr and Katharine Strunk from the Michigan State University Education Policy Initiative Collaborative (EPIC). We are grateful to all the educators who took time to participate in this study to share their experiences and advice. We hope the following report and resources help provide strategies to support the vital social and emotional needs of our educators.

The school is a machine, teachers are the gears, students are the output. This year, administration has focused on the beauty of the machine and the quality of the output. No one is looking to maintain the gears. The gears are jamming, the gears are breaking, there are no replacement gears available. Please focus on the gears.

Introduction and Need for Study

K-12 teachers and administrators are among the most dedicated essential workers in communities across the country. However, research has shown that the well-being of these educators has been on the decline in recent years, especially during the 2020-21 academic year amid uncertainties of the COVID-19 pandemic (Babb et al., 2020; Dickler, 2021; Kazee et al., 2020; Meltzer, 2020; Moss, 2021; Singer, 2020). Beyond the pressures to meet school and state benchmarks with additional COVID-19 related demands, K-12 educators need to mentor students, tailor lessons to students’ varying needs, and manage student behavioral issues. More so than ever, K-12 educators have found themselves being continuously stretched thin and burned out (Babb et al., 2020; Dickler, 2021; How Teachers Can Manage Burnout, n.d.; Meltzer, 2020; Moss, 2021; Pressure of COVID-19 Pandemic, 2021; Pepin 2021; Singer 2020; Will 2021).

During a typical day, K-12 educators focus their attention on meeting students’ educational, emotional, and physical needs, which may mean that they have to skip breaks and work outside normal working hours (all without extra pay) to ensure they complete necessary lesson planning and other administrative tasks. Concerning studies indicate that about 15% of US teachers leave their positions each year with 41% leaving the profession within their first 5 years (Kazee et al., 2020). A shortage of teachers amplifies these concerns because if educators are leaving the field, the prospects of replacing them dwindle (Russell, 2021). Thus, it is essential that the social and emotional learning (SEL) needs of K-12 Michigan educators are addressed and understood for the future of education in the state, especially as educator stress and fatigue have been exacerbated in the last year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In news reports and surveys around COVID school closures and emergency remote learning, teachers reported worrying about the social and emotional well-being of their students (Babb et al., 2020; Dickler, 2021; Harris, 2021; Karnovsky, 2021; Meltzer, 2020; Moss, 2021; Natanson et al., 2021; Tseng, 2021; Singer, 2020; Will, 2021). Many teachers and administrators also indicated that they felt overwhelmed themselves. According to Michigan-based SEL consultant Lauren Kazee, in order for students to build their own SEL skills and maximize their learning, school teachers and administrators need to have their well-being and SEL needs met first.

Research Questions

With much of the focus on students’ SEL needs during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study focuses on several questions to better understand how teachers’ and administrators’ SEL needs are being met:

- What is the current state of Michigan educators’ emotional well-being?

- What social and emotional support was offered by schools or districts to Michigan educators during the 2020-21 school year?

- What effective strategies did educators implement to meet their own social and emotional needs?

- How did Michigan districts support administrators’ emotional well-being?

- What are the challenges to providing social and emotional support to educators?

This study, conducted by researchers at Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute (MVLRI), assesses the SEL resources and supports that have been used to help Michigan teachers and administrators. Through an online survey of 278 K-12 educators across the state of Michigan (166 teachers and 112 administrators), we examined what district and schoolwide resources have been leveraged, and what strategies teachers and administrators have used to help themselves, which ultimately benefits students, families, and communities. Additionally, attention was paid to the perceived effectiveness of these resources and strategies and challenges associated with their implementation. It should be noted that throughout this report, the word educators is used to refer to K-12 teachers and administrators.

Through this study, by understanding Michigan K-12 educators’ well-being and their SEL needs, we hope that teachers and administrators can find ways to meet their SEL needs and maintain a positive well-being, which will ultimately make their jobs more satisfying and fulfilling. We also hope that educators come to realize that they are not alone in facing similar struggles and that this report will help start and continue important conversations about how to provide SEL supports to them. Such supports not only help educators, but they also help students, families, and communities because educators can be most effective and feel most fulfilled in doing their jobs.

Knowledge about mental health prevalence is missing. Most teachers and administrators just aren’t aware of how many students/staff may be dealing with a mental health disorder. Increased awareness can increase understanding and compassion and potentially reduce frustration, anxiety, and/or other emotions when working with staff/students that are already struggling.

What is Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)?

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) defines social and emotional learning (SEL) as the ability to manage emotions, feel and show empathy for others, and establish caring, supportive relationships (What is SEL?, n.d.). Through increased SEL, people are not only self-aware, but they also build empathy and compassion for others, which has been shown to address inequities and biases found in society (Social Emotional Learning Activities, n.d.).

However, SEL is not just a learning objective for students. In order for students to build and achieve high levels of SEL, a systemic approach is required. According to CASEL’s SEL framework, it is necessary to understand community and family needs as well as have schoolwide cultures, practices, and policies that proactively create “a work environment in which staff feel supported, empowered, able to collaborate effectively and build relational trust, and also able to develop their social and emotional skills” (Social Emotional Learning Activities, n.d.). Therefore, if students are to benefit from SEL, teachers and administrators need to have their SEL needs understood and met just as much as students.

Drawing from psychology, the “Big Five” Personality Model is another way to conceptualize SEL, which the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) is using in an ongoing multi-country study about social and emotional learning in schools (About the OECD’s Study, n.d.). Within the OECD SEL study, the following traits are deemed important to building one’s social and emotional skills:

- task performance (self-control, responsibility, persistence)

- emotional regulation (stress resistance, optimism, emotional control)

- collaboration (empathy, trust, cooperation)

- openness (tolerance, curiosity, creativity)

- engaging with others (sociability, assertiveness, energy)

As a CASEL article notes, the application of the “Big Five” personality model to SEL does not mean that the goal is to make people cookie cutters of each other with the same personality traits (On the Use of the Big Five Model, n.d.). Rather, the idea is to meet students where they are and help them organize and regulate their social and emotional needs and skills to succeed in school, work, and life.

The demands being put on educators over the past year is just too much. Now that we are in-person, the responsibility of contact tracing and quarantining takes hours every week. And on top of everything else we need to do we now have to administer the M-STEP and WIDA. It is just too much being asked of us on top of our already stressful jobs and trying to keep ourselves and staff physically safe and mentally healthy.

Why SEL Matters

When teachers and administrators are aware of what SEL is, they can help students achieve their own SEL needs and build valuable skills. However, educators’ specific and unique SEL needs should also be addressed, understood, and considered in the workplace. Identifying these needs is especially important based on the demands brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic where remote and hybrid teaching have become regular modes of instruction, increasing educators’ workloads and levels of stress, anxiety, and burnout.

There are significant dangers in not meeting the SEL needs of teachers and administrators. When educators do not have an opportunity to work on their wellness and self-care needs, they may end up with compassion fatigue, which is “the sense of being overwhelmed, emotional numbing, and irritability people may experience when serving others” (Kazee et al., 2020). Continuing to face this “cost of caring,” educators, like others in caretaking positions such as nurses and doctors, may become burned out based on their “state of emotional and mental exhaustion caused by stress, which can lead to lack of interest, low morale, and dissatisfaction” (Kazee et al., 2020). When burnout is sustained over time, educators may face frustrating and ineffective performance in the classroom, which can lead to early exits from careers in education. When teachers and administrators continue to leave education at alarming rates, there are tremendous costs in managing this turnover. Therefore, it is vital to understand Michigan K-12 educators’ SEL needs, roadblocks, and effective practices to help the future of education in the state.

I am getting burnt out because of all of the things I’m required to do that are not actually teaching. This was a problem before the pandemic, but now it feels ridiculously overwhelming. I wish I could just teach. We should be given opportunities to take mental health days without having to make excuses (but then we run into a sub shortage).

Methodology

This study used an anonymous survey through the Qualtrics online survey software to collect data from 278 K-12 teachers and administrators across the state of Michigan (166 teachers, 112 administrators) from mid-April to mid-May 2021. These educators were recruited by sending announcement emails and social media messages through several professional networks, including that of SEL consultant Lauren Kazee, the Michigan Elementary and Middle School Principals Association (MEMSPA), Michigan State University’s Education Policy Initiative Collaborative (EPIC), and the State of Michigan’s Center for Educational Performance and Information (CEPI). Questions asked participants to provide detailed information about their school’s primary mode of instruction in the last year, academic level of teaching or administration (e.g., elementary, middle, high school), concerns about students’ SEL needs, SEL training experience, self-reported assessments of burnout, identification of roadblocks to meeting educators’ SEL needs, and effective practices to help meet SEL needs. Administrators were asked specific questions about the SEL support their schools or districts may have provided to them and their faculty and staff. In order to identify Michigan educators’ SEL needs, and to gauge the urgency of implementing SEL supports in Michigan schools, this study asked participants to assess their burnout and frustration with their work using reliable and valid self-assessment measures found in other research studies on these topics (“Valid and Reliable Survey Instruments,” n.d.). All participants were asked optional demographic questions including years of experience in K-12 education, gender, and race and ethnicity.

The demographics of participants in this study did not correspond exactly with those reported by the Michigan Department of Education (MDE) for all sub-categories (see Tables 2-5 in Appendix for a full breakdown), which may not make the findings generalizable. Also, the questionnaire, while anonymous, involved self-selected participants providing self-reported information, which may make the findings subject to social desirability bias. Despite these limitations, though, we feel strongly in the accuracy and importance of what is reported here by the Michigan educators who participated in our study. It lends support for further research and discussion of Michigan educators’ SEL needs and how to meet them.

My decision to leave education this year has solely been based on burnout and inability to manage my physical, emotional and family wellness due to the tolls of my profession. 4 principals are leaving my district at the end of this year, and 4 of my district’s directors left at some point in the last school year. This is an unusual and unfortunate trend in a profession that is so important and valuable.

Results and Discussion of the Findings

This study aimed to assess Michigan educators’ emotional well-being, social and emotional supports offered by schools and districts, effective strategies educators pursued on their own to meet their SEL needs, administrators’ well-being and district-level support, and overall challenges educators face in meeting their SEL needs. This section covers what the study’s survey revealed about each of these respective topics.

Michigan Educators’ Emotional Well-Being

The survey revealed alarming rates of burnout and frustration among Michigan educators, as discovered through a series of burnout and frustration indicators (see Tables 8-10 in Appendix). A vast majority (84%) of all participants indicated that they felt burned out from work in the last month. Nearly three-quarters of administrators, and two-thirds of teachers felt that all of the things they had to do were piling up so high that they could not overcome them. A majority of teachers and administrators (over 60% for both groups) indicated that they were bothered by feeling down, depressed, anxious, or hopeless, and nearly two-thirds of educators felt worried that work had disconnected them emotionally. When the data are broken down by gender, women indicated higher burnout rates than men across all burnout indicators, especially for the general question, In the last month, have you felt burned out from work? (88.3% for women versus 73.7% for men). Such a difference lends support to the need to adapt SEL resources to specific groups of people; some educators, depending on the demographics in question, may be impacted more or in particular ways, which requires not taking a blanket approach to identifying and providing SEL supports to educators.

When self-reported burnout assessments are examined by occupational role, administrators reported higher levels of agreement with the statement, In the last month, have you felt that all the things you have to do were piling up so high that you cannot overcome them? (73.2% for administrators and 65.7% for teachers). Teachers had higher levels of agreement (71.1%) with the statement of being bothered by feeling down, depressed, anxious, or hopeless compared to administrators (64.2%). These figures indicate that a majority of educators are likely overwhelmed by the amount of work they have to do and need mental health support.

When asked if they thought about leaving education within the last year, nearly two-thirds of teachers said yes; administrators reported feeling more hopeful about the future with less than half saying they considered leaving education. Nearly three-quarters of teachers were frustrated with the modality that their school used to teach in the last year, and administrators again were more optimistic about this. Among teachers, hybrid and asynchronous online/remote teachers cited being frustrated with their teaching modality at higher rates compared to in-person and synchronous online/remote teachers. When combined with the burnout figures noted above, all of these frustration indicators sound an alarm that teachers’ dissatisfaction with their work and their feelings of being overwhelmed by new and continually increasing demands need to be addressed.

All participants were also asked a series of five-point Likert scale questions where they evaluated their work and their comfort with expressing their emotions and seeking help. All educators had a strong agreement with the statement, The work I do is meaningful to me. However, when asked to evaluate the statements, My work schedule leaves me enough time for my personal/family life and I feel comfortable showing a range of emotions in my job, neither administrators nor teachers felt more positively than neutral agreement or indifference. When asked to evaluate the statement, I feel comfortable talking with someone at school if I need help, only administrators reported slightly higher than neutral agreement.

Responses show that Michigan educators find value in the work they do, but there are concerns about managing time and responsibilities, especially administrators. Although it may not seem alarming that all categories of educators were mostly neutral with expressing emotions and seeking help, such a tepid agreement with these statements should be cause for concern given two of SEL’s core competencies: being able to express oneself emotionally without fear and seeking help from others when it is needed.

School or District Offered Social and Emotional Support

Michigan educators were asked what SEL supports were offered to them by their schools or districts. Over a third reported that they were offered extra planning/prep time. About a third noted that counseling services were provided. A little over a quarter were offered mindfulness exercises (e.g. yoga, meditation). Additionally, as illustrated in Figure 1, when comparing what administrators and teachers reported as the SEL supports offered to them, teachers consistently reported at lower levels for all options except for none. This observation and the finding that a quarter of all educators noted that no SEL supports were offered to them during the 2020-21 academic year is rather alarming given the many stresses brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1. SEL Supports Offered by Schools/Districts to Educators (See Table 11 in Appendix for Specific Numbers)

Educators’ Effective Strategies for Meeting Their Own Social and Emotional Needs

While many educators reported needing more support from their schools and districts, they pursued strategies to meet their own SEL needs. Educators were asked to share effective practices that have helped meet their SEL needs. Nine themes emerged from participants’ open-ended responses.

Prioritizing Mental Health and Mindfulness. One of the top cited effective practices involved prioritizing mental health and mindfulness through the use of mindfulness mobile phone apps (e.g., Calm and Pause), which were provided by school districts in some cases. Other educators started or continued professional therapy or engaged with community mental health organizations and resources. Many educators took up meditation exercises, deep breathing, and visualizations. Some regularly prayed or engaged in spiritual pursuits. Several educators regularly rewarded themselves with massages or took time off to distance themselves from their work and pursue opportunities to “get away.”

Exercising and Physical Health. Another regularly mentioned strategy was exercise and focusing on one’s physical health. Several participants mentioned that they bought new exercise equipment (e.g., indoor exercise bike) or found ways to continue their exercise routines that couldn’t be done at a gym. Others focused on eating healthier, drinking more water, getting outdoors, sleeping more, and purposefully taking breaks throughout the workday (often involving walks in one’s neighborhood).

Revisiting Hobbies. Many participants continued or took up hobbies they found relaxing and meaningful, such as watching favorite television shows and movies, playing video games, completing puzzles, reading, and doing crafts. A few educators noted that the pandemic gave them an opportunity to enjoy old hobbies they had not taken up for some time.

Prioritizing, Boundary Setting, and Incentivizing. Given how this study’s survey revealed educator feelings of being overwhelmed with the amount of work they have to do, it is no surprise that some effective strategies focused on saving time and setting clear boundaries between work and personal life. Many educators said that they set firm work-life boundaries by not doing work after a certain time of the day, not bringing work home from school, or turning on out-of-office automated messages on weekends. To balance many competing priorities, some educators noted that they kept priority task lists and only focused on the most essential and important things to do. Lastly, several educators gave themselves rewards such as a special treat (e.g., coffee, meal) for having accomplished something.

Utilizing Community Support. A significant number of educators said that they talked with friends and family regularly. Others, as noted earlier, joined community-based therapy and counseling. Some engaged in community support groups like Happy Teacher Revolution, an organization focused on supporting educators’ mental health and wellness.

Taking Digital Breaks. Given the intensity of using digital tools to teach and work during the COVID-19 pandemic, many educators said that they scheduled breaks from technology. In one case, a participant suggested putting technology in another room so one cannot be tempted to check emails or do work during a break.

Self-Acceptance and Resisting Perfectionism. Several educators said that they resisted the stress they felt by being perfectionists. These educators said that they lowered their expectations and let go if everything could not be completed “perfectly.” An educator noted it was necessary to be kind to oneself and realize that one can’t always get everything done on a checklist. Telling oneself that essential tasks will get completed later was an effective way of managing the stress of trying to keep up with many responsibilities during uncertain times.

Creating Routines to Support and Encourage Time for SEL. Some participants pursued deliberative practices and routines that supported and encouraged social and emotional learning. Some teachers incorporated SEL strategies in classroom routines and activities. Other educators completed training to find better ways to use technology to make teaching and learning more efficient and minimize time pressures. Some participants met with colleagues at the same time each day/week to check in and catch up.

Maladaptive Strategies. Although they are not strategies to emulate, a small number of educators were honest about their pursuit of maladaptive coping mechanisms. Some managed their stress and anxiety by consuming alcohol or legally permitted recreational substances.

Administrator Well-Being and District-Level Support

Given administrators’ important roles in overseeing policies, operations, and school/district culture, this study’s survey also asked administrators a specific question about strategies they pursued to support their SEL needs as school and district leaders. A question also assessed what district-level support administrators were provided. Administrators’ responses to general questions about SEL were included in the overall educator strategies included above, but responses to administrator-focused questions are presented in this section. Overall, when administrators were asked, What effective strategies has your school or district put into place to support your social and emotional needs as an administrator?, their responses typically fell into one of three categories: no strategies, logistical strategies, and/or personal strategies.

Approximately half of the responses indicated that their school or district did not implement any strategies to support administrators’ social and emotional needs. There was a feeling of discouragement among this group and assumptions that they were on their own. These administrators did, however, note strategies that they tried to implement with their staff, perhaps trying to fill the school or district-level gaps.

Administrators who reported school- or district-level strategies indicated either personal (i.e., supporting the emotional well-being of an individual) or logistical supports providing an emotionally supportive environment. Administrators noted schools or districts offering new or increased leadership coaching and mentoring as administrators navigated the 2020-21 school year. Additionally, administrators reported that their districts offered access to mindfulness and meditation apps, as well as counseling and mental health services like tele-therapists. Finally, administrators cited increased collaboration among staff, which can provide social connections, emotional support, and collaborative problem solving.

Logistically, administrators reported having new or increased flexibility in their work location and to some degree their work hours (outside of school hours) as well as additional staffing during the 2020-21 academic year. Additional staffing took many forms in administrators’ responses from one noting the hiring of a summer school coordinator to many others reporting the hiring of additional support staff in their building.

Administrators were also asked what successful strategies they implemented to meet their own social and emotional needs, either in place of, or in addition to school or district-level supports. Unsurprisingly, these strategies closely mirror those of teachers overall with strategies around mindfulness, physical exercise, and boundary setting being the most common. As with district provided strategies, however, there were a number of administrators who noted that they did not pursue any strategies, often for lack of time or energy.

Strategies around prioritizing mental health and mindfulness were most often cited. These included (but certainly aren’t limited to) counseling and therapy, meditation and yoga, and prayer and bible study. Physical exercise was also commonly noted, including going to the gym, taking breaks from work to take a walk, and taking up new physical activities such as jogging or cycling.

Finally, many administrators also reported setting more firm work life boundaries and making time with their families a priority. This strategy, however, was easier said than done and was contingent on a number of other factors that will be discussed further in the next section.

The role of the administrator is a unique one in that they are responsible for the social and emotional needs of their staff, yet face many of the same pressures—likely more from the district—and may not be receiving the support they offer to their own staff and need themselves.

Challenges To Providing Social and Emotional Support to Educators

Providing SEL support to educators is an important goal, but implementation is easier said than done. Pursuing and providing SEL supports may seem daunting given the many responsibilities already placed on teachers and administrators to do their jobs within rigid time constraints. Therefore, in order to determine effective practices teachers and administrators can pursue, one must understand the challenges and roadblocks educators face to meet their SEL needs in the first place.

General Challenges for Teachers and Administrators

In this study’s survey, educators were asked to identify what they saw as the top three roadblocks they faced to meet their SEL needs. Among the nine options provided, the following were the top four roadblocks chosen: lack of time, too many responsibilities to get their job done, inability to socialize with colleagues, and SEL not being a priority in school/district. Figure 2 provides a complete breakdown of the top roadblocks chosen among all educators participating in this study.

Figure 2. Top Roadblocks to Meeting SEL Needs Reported by Educators, Broken Down by Role (See Table 12 in Appendix for Specific Numbers)

These figures reinforce the observation that Michigan educators are most overwhelmed with the amount of work required to complete their jobs, with administrators feeling the burden slightly more than teachers. This may be attributed to the extra responsibilities administrators faced during the 2020-21 academic year, such as developing and revising new protocols as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded. Given that educators have cited time and job responsibilities as the most significant roadblocks to meeting their SEL needs, attention should be paid to how to provide streamlined ways to incorporate SEL supports within everyday work and educating practices. Such roadblocks are not surprising given educators’ finding tools to streamline their work to be a significant topic to address their SEL needs.

Having nearly one out of four educators working in an environment where SEL is not seen as a priority is cause for concern, especially given what research reveals about educating in an environment not supportive of SEL needs. Educators have a higher chance of burning out and may leave the education field if their SEL needs are not met.

Educators were also given the opportunity to provide roadblocks that they encountered that were not on the survey list. These responses were grouped into the following key themes:

- Operating in a constant state of crisis and change; no consistency in operations and too many last-minute changes without adequate notification or preparation

- Working in a polarized political environment

- SEL perceived as a sign of weakness or poor performance

- Having to juggle multiple modes of instruction at the same time

- Need to develop new systems, procedures, and forms of monitoring with little to no preparation time (e.g., hybrid learning, working with quarantined students, COVID requirements, and monitoring/maintaining student attendance)

- Inconsistent and limited guidance from school and district administrators as well as state-level officials

- Administrators presenting overly complex solutions to various problems

- Lack of student motivation or engagement

- Lack of funding for schools/districts to implement SEL supports

- Balancing work and family obligations

- Not enough support staff in classrooms

- A focus on meeting students’ SEL needs over that of faculty and staff

Challenges for Teachers Based on Mode of Instruction

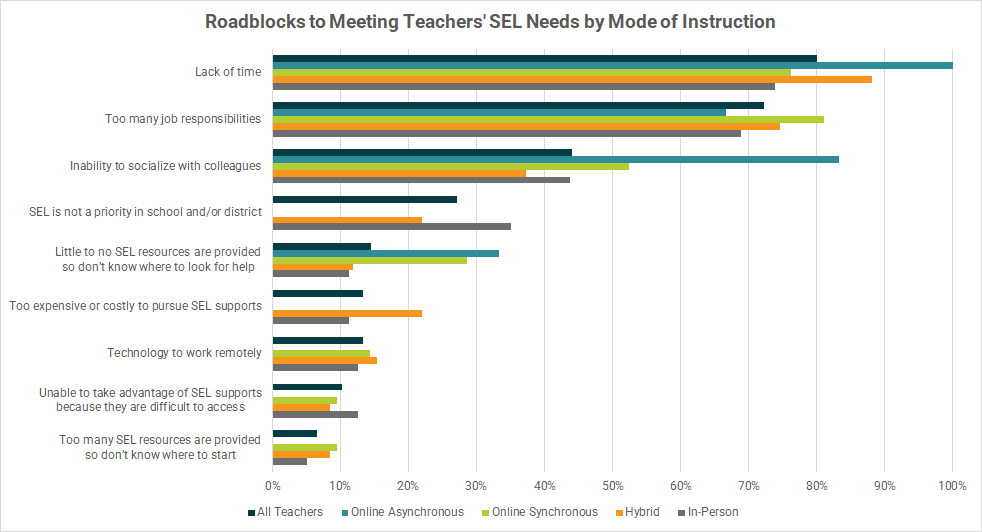

When teachers’ responses to questions about challenges to meet their SEL needs were examined closely based on how they delivered their classes during the 2020-21 academic year, lack of time was ranked highly across all teachers surveyed, regardless of their primary mode of instruction. Too many responsibilities to get my job done was also cited as a major roadblock. Among asynchronous online/remote teachers, inability to socialize was the second most chosen (83.3%) after lack of time (100%). Figure 3 provides a complete breakdown of teacher responses related to roadblocks.

Figure 3. Top Roadblocks to Meeting SEL Needs Reported by Teachers, Broken Down by Primary Mode of Instruction (See Table 13 in Appendix for Specific Numbers)

All online teachers (synchronous and asynchronous) chose inability to socialize at higher rates than their in-person and hybrid counterparts, which flags the importance of providing teachers with opportunities to socialize when they teach exclusively online. This need is very apparent when examining how participants responded to the question, At any point in the last month, have you worried work has disconnected you emotionally? All asynchronous online/remote teachers (n=6) responded “Yes” to this prompt compared to two-thirds of in-person teachers, and slightly more than half of hybrid teachers and synchronous online/remote teachers.

Although the total number of asynchronous online teachers was low, their responses deserve special attention given the nature of this mode of instruction. Asynchronous educators have no physical interactions with their students, and likely no physical interactions with other educators. This is apparent in their concerns about meeting their own social emotional needs, noting the inability to socialize with my colleagues as a significant roadblock, nearly double that of educators in other settings. Additionally, asynchronous educators reported increased concerns over student attendance and engagement, maintaining their own positive health, and socializing.

Educators in asynchronous settings also reported the greatest feelings of frustration with the mode of education selected by their district as well as the highest percentage considering leaving education. For teachers who may not have had a choice in teaching asynchronously online, it seems the isolation from both students and fellow educators has weighed heavily on them during the 2020-21 academic year further highlighting the need for effective educator support strategies—no matter the mode of education.

We are constantly being told that we need to meet the social and emotional needs of our students and their families…..where is the support for us? When I’m empty, there is nothing I can give to anyone else!

Implications

This study surveyed 278 K-12 teachers and administrators in Michigan to assess several topics: the current state of Michigan educators’ emotional well-being, what social and emotional supports schools or districts offered Michigan educators during the 2020-21 academic year, the effective strategies Michigan educators implemented to meet their own social and emotional needs, how Michigan districts supported administrators’ emotional well-being, and the challenges of providing social and emotional support to Michigan educators. The survey revealed that over two-thirds of educators felt burned out or frustrated with their work and the amount of support and recognition they received. Across all educators, lack of time and too many job responsibilities were reported as the most significant roadblocks to meeting their SEL needs. During the 2020-21 Academic Year, the added responsibilities brought on by the constantly changing situation of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these concerns. So how can schools and districts better support educators’ SEL? There are several free and inexpensive ways schools, districts, administrators, and teachers can address and meet educators’ SEL needs.

Show Concern for Adult SEL, But Don’t Force It

Unfortunately, nearly 25% of participants indicated that SEL is not a priority in their school and/or district. Such findings are concerning given the high degree of burnout exhibited by those taking this study’s survey. To help educators meet their SEL needs, schools and districts should first show that they understand and value SEL for both students and adults. Acknowledging that adults have their own social and emotional needs to be met in their challenging and rewarding roles as educators would go a long way in setting a tone that the well-being of everyone in the school matters. However, showing concern for SEL and providing SEL support should not be forced. There may be discomfort for some in pursuing SEL because they may prefer to seek out SEL support on their own. Some also may feel like addressing SEL for adults is another administrative burden to add on to their plates, as one educator stated: “Adding SEL to the classroom feels like one more thing placed on teachers in the classroom when we are already overwhelmed.” Therefore, it would be helpful to conduct a climate survey of adults within a school or district to see where they are in relation to burnout, compassion fatigue, SEL needs, and SEL support preferences.

Build a Community of Empathy and Trust

One easy way to show concern about educators’ SEL needs is to build a community of empathy and trust. In addition to checking the pulse of how teachers and administrators feel, it would help to explicitly communicate that it is okay to not be okay and that all emotions can be expressed and shared with others, including students, without worry of being ostracized or punished. When educators are encouraged to bring their whole selves to the workplace, they can then more effectively manage and address their emotions while modeling good behavior among students and members of the community. Creating a community that values sharing and respects people’s emotions and feelings will build trust and compassion, which encourages colleagues and students to support one another’s SEL needs. Moreover, having administrators clearly state to everyone that it is okay to seek help and support from each other or from a list of available and recommended resources goes a long way to show that everyone is working in a caring and supportive school or district.

Address Time Constraints and Heavy Workloads

Time was the most significantly cited roadblock to meeting educators’ SEL needs. When teachers and administrators feel overwhelmed by the amount of work they need to do within set time constraints, attention should be focused on examining workloads to make them more manageable for everyone. This may require an assessment of teaching and administrative assignments, a close look at curricula requirements and grading to see if any adjustments are needed to meet learning objectives in a more streamlined manner, and providing teachers and administrators with tools, resources, and advice on how to do their work more efficiently. By offering tools and resources that allow teachers and administrators to focus more on building a positive learning environment for their students (rather than checking off items from an administrative checklist), educators can focus on what most likely inspired many of them to pursue a career in education in the first place.

Integrate SEL into Everyday Work

Related to the time constraints educators face, one strategy to meeting teachers’ and administrators’ SEL needs is to integrate SEL more organically into everyone’s work. The goal would not be to tack on extra work or to jam more requirements into an already busy schedule. Two participants summarized this point succinctly: “I think admin needs to stop PUSHING self-care, ‘make sure you go home and focus on self-care!’. They should provide opportunities for in-school self-care!” and “I think we need to look at offering these supports within the school day as much as possible, walking the walk by embedding self care plans and activities into staff evaluations, and talking about our feelings openly.”

Therefore, one goal is to find ways to integrate SEL into tasks and meetings that are already required. For example, teachers can lead short meditation exercises in class, or administrators can facilitate short mindfulness exercises at the start of a meeting. Already planned in-service and training days can focus on SEL supports or at least incorporate some SEL-focused activities. Educators can also be encouraged and given time to earn professional development “credit” within their schools or districts for completing courses related to SEL. Moreover, at the level of school policies and learning community philosophies, a statement related to supporting everyone’s emotional and social well-being can be written, shared, and emphasized for all. This means that administrators need to take the lead in creating awareness around SEL and being intentional about communicating what supports are available to teachers to meet their SEL needs. Without doing so, there is a risk of teachers not feeling fully supported, as one participant noted: “Our staff has been encouraged to do everything we can to meet the needs of our students, to the point where we are neglecting our own needs. There has not been much input about this from our administration, except for them to state ‘We want you to take care of yourselves.’ but they do not help us learn how to do so.”

Pursue Free or Cost-Effective SEL Supports

Providing SEL support and resources do not need to be expensive. Many educators cited the use of free or inexpensive mindfulness apps like Calm or Pause. Teachers and administrators can also come together to share the free or cost-effective SEL supports that have worked for them within their local community. There may be support groups, exercise classes, hobby clubs, or other community-based activities that can help create a positive and supportive learning environment within and beyond the walls of the classroom.

Reward and Recognize Educators

One of the simplest and most cost-effective ways to boost educator morale and feelings of accomplishment in the workplace is to reward and recognize the hard work educators do. One participant stated this quite clearly: “More needs to be done for teachers to prevent burn out. Make them feel needed and appreciated.” Another educator suggested making sure the community better understood teachers’ accomplishments and their needs: “The great efforts of our educators need to be more visible to parents and communities. Ideally, leading to increased support for teachers.” A teacher also said the simple things like small treats can go a long way to start off a teacher’s day on a happy note: “Be flexible. Listen and support teachers. Bring them treats from time to time … like Tim Horton’s ‘iced cappuccino’ or whatever will help them start the morning on a positive note.” Rewarding and recognizing teachers’ and administrators’ hard work within and beyond the walls of a school would make educators feel more appreciated for what they contribute to their communities.

Encourage and Provide Time for SEL Training

One interesting survey finding is that those educators who engaged in SEL training reported lower burnout, frustration, and compassion fatigue rates. Although SEL training is not the sole determinant for more job satisfaction and higher levels of SEL support, providing and encouraging SEL training through free or cost-effective programs may magnify the benefits that come with pursuing other SEL supports. Again, caution should be made when offering SEL training to teachers and administrators. If the training is an additional requirement outside of regular working hours, SEL training may be seen as a burden. Providing training within the regular workday, or during anticipated, scheduled meetings or instructional in-service days should be considered to maintain enthusiasm for SEL training in a school or district.

We need to check on each other. Everyone is so busy in their own classroom that it’s hard to remember to make sure our colleagues are OK.

Conclusion

This study examined Michigan teachers’ and administrators’ emotional well-being, the social and emotional supports offered to them, effective strategies to meet their own social and emotional needs, and ways to overcome the challenges of providing social and emotional supports to educators.

In the end, providing SEL support to teachers and administrators is necessary to build supportive and welcoming learning environments for everyone. Addressing the SEL needs of all adults in schools will model its importance for students, families, and communities. Educators will have opportunities to learn how to understand, manage, and express their emotions, which will help them serve as positive role models for students. Moreover, when educators’ SEL needs are known, and educators are given time and permission to address them, steps can be taken to mitigate burnout, frustration, and compassion fatigue that have led to attrition and less effective teaching.

Solutions do not need to be costly or time consuming. By taking the pulse of a school’s or district’s SEL needs and leveraging various free or low-cost digital and community resources to support educators, educators can feel supported and have outlets to seek the help that they need to be successful and satisfied in their roles in our schools and communities. SEL consultant Lauren Kazee emphasizes these concluding points through some advice she gives regularly in training across the state of Michigan: “Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can. It’s OK to take baby steps forward as long as you are moving forward. We didn’t get to this place of feeling overwhelmed and burned out overnight. Unfortunately, things won’t change overnight, but small steps can be taken to move forward and eventually get to where we want to be.”

References

References

About the OECD’s study on social and emotional skills—OECD. (n.d.). OECD. https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/social-emotional-skills-study/about/

Babb, J., Sokal, L., & Trudel, L. E. (2020, June 16). How to prevent teacher burnout during the coronavirus pandemic. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/how-to-prevent-teacher-burnout-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic-139353

Dickler, J. (2021, March 1). More teachers plan to quit as Covid stress overwhelms educators. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/01/more-teachers-plan-to-quit-as-covid-stress-overwhelms-educators.html

Harris, B. (2021, March 9). Tears, sleepless nights and small victories: How first-year teachers are weathering the crisis. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/tears-sleepless-nights-and-small-victories-how-first-year-teachers-are-weathering-the-crisis/

How teachers can manage burnout during the pandemic. (n.d.). Rutgers Today. https://www.rutgers.edu/news/how-teachers-can-manage-burnout-during-pandemic

Karnovsky, S. (2021, February 28). Teachers are expected to put on a brave face and ignore their emotions. We need to talk about it. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/teachers-are-expected-to-put-on-a-brave-face-and-ignore-their-emotions-we-need-to-talk-about-it-153642

Kazee, L., Brandow, C., and Cook, O. (2020). Self-care and wellness: An important focus for staff implementing a school responder model. National Center for Youth Opportunity and Justice. https://ncyoj.policyresearchinc.org/img/resources/SelfCareWellnessBriefFinal-943347.pdf

Meltzer, E. (2020, December 3). ‘Stretched thin’: Superintendent survey highlights concerns with teacher burnout, learning loss. Chalkbeat Colorado. https://co.chalkbeat.org/2020/12/3/22150072/colorado-education-needs-assessment-teacher-burnout-learning-loss

Moss, J. (2021, February 10). Beyond burned out. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/02/beyond-burned-out

Natanson, H., George, D. S., & Stein, P. (2021, February 20). More teachers are asked to double up, instructing kids at school and at home simultaneously. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/teachers-remote-in-person-simultaneously/2021/02/20/8f466ff8-6bb9-11eb-9ead-673168d5b874_story.html

On the use of the big five model as a SEL assessment framework—AWG. (n.d.). Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. https://measuringsel.casel.org/use-big-five-model-sel-assessment-framework/

Pressure of COVID-19 pandemic raises concerns about Michigan teachers getting burned out. (n.d.). https://www.clickondetroit.com/news/local/2020/09/29/pressure-of-covid-19-pandemic-raises-concerns-about-michigan-teachers-getting-burned-out/

Pepin, A. (2021, February 12). Burnout prevention series aids aspiring and current teachers with pandemic fatigue. The Appalachian. https://theappalachianonline.com/burnout-prevention-series-aids-aspiring-and-current-teachers-with-pandemic-fatigue/

Russell, K. (2021, May 20). “Perfect storm” of events causing teacher shortage crisis in Michigan. WXYZ Detroit 7. https://www.wxyz.com/news/perfect-storm-of-events-causing-teacher-shortage-crisis-in-michigan

Singer, N. (2020, November 30). Teaching in the pandemic: “This is not sustainable.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/30/us/teachers-remote-learning-burnout.html

Social Emotional Learning Activities for Adults | CASEL – Casel Schoolguide. (n.d.). Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. https://schoolguide.casel.org/focus-area-2/overview/

Teaching: Before Rolling Out Post-Pandemic Plans, Let People Grieve. (n.d.). Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/teaching/2021-03-04

Tseng, A. (2021, March 3). How can we support teachers and their mental health amid COVID-19? Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-03-03/how-to-help-teachers-mental-health-covid-19

Valid and Reliable Survey Instruments to Measure Burnout, Well-Being, and Other Work-Related Dimensions. (n.d.). National Academy of Medicine. https://nam.edu/valid-reliable-survey-instruments-measure-burnout-well-work-related-dimensions/

What is SEL? (n.d.). Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. https://casel.org/what-is-sel/

Will, M. (2021, January 6). As teacher morale hits a new low, schools look for ways to give breaks, restoration. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/as-teacher-morale-hits-a-new-low-schools-look-for-ways-to-give-breaks-restoration/2021/01

Additional Recommended SEL Resources for Educators

Websites

Cornerstone for Teachers – National Certified Board Teacher Angela Watson provides a variety of resources for teachers on how to stay motivated, find ways to minimize stress, and manage their many responsibilities.

Cult of Pedagogy, “12 Ways Teachers Can Build Their Own Resilience” – This article provides a summary of key tips from Elena Aguila’s book Onward: Cultivating Emotional Resilience in Educators.

Happy Teacher Revolution – A support network for teachers to collectively face the many challenges they face related to time, money, and emotional capacity.

LivingSLOW – Michigan-based social-emotional learning consultant Lauren Kazee offers self-care and wellness advice and resources for educators.

Michigan Department of Education (MDE) Social and Emotional Learning Information – The Michigan Department of Education (MDE) provides a variety of social and emotional learning information, programs, and resources for Michigan educators, families, and communities.

Teacher Self-Care Conference – Information about a regular conference focused on how to address and manage teacher stress.

Zen Teacher – A veteran high school English teacher provides advice and resources on implementing self-care and wellness strategies in schools.

Books

Aguila, E. (2018). Onward: Cultivating emotional resilience in educators. Jossey Bass.

Brackett, M. (2019). Permission to feel: Unlocking the power of emotions to help our kids, ourselves, and our society to thrive. Celadon Books.

Carlson, R. (2008). Don’t sweat the small stuff…and it’s all small stuff: Simple ways to keep the little things from taking your life. Hodder Mobius.

Connors, N. (2013). If you don’t feed the teachers they eat the students!: Guide to success for administrators and teachers. Incentive Publications.

Covey, S. (1990). The 7 habits of highly effective people: Powerful lessons in personal change. Free Press.

Mason, C., and Rivers Murphy, M. (2018). Mindfulness practices: Cultivating heart centered communities where students focus and flourish. Solution Tree Press.

Watson, A. (2019). Fewer things, better: The courage to focus on what matters most. Due Season Press and Educational Services.

Videos

Edutopia. (2017, May 8). How do teachers change lives? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=omf9mPTHP9M

Google for Education. (2020, May 4). 2020 Teachers of the year on practicing self care. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n3pdoe1hfuE

Prioritizing teacher self-care. (n.d.). Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/video/prioritizing-teacher-self-care

Appendix

Notes

The following tables provide an overview of the composition of participants who took part in this study’s survey. Some tables provide comparisons with 2020-21 K-12 Staffing Count data provided by the Michigan Department of Education’s MI School Data site.

These data are provided to emphasize Michigan Virtual’s efforts to be transparent in trying to be equitable and inclusive of diverse perspectives in its research. The following tables reveal that this study was roughly on par in reflecting the gender composition of Michigan’s teachers and administrators. More efforts are needed in future research to include more teachers and administrators of color as well as early career educators.

Demographic Tables (Tables 1-5)

Table 1

MVLRI SEL Study Participants by Grade Level

| Grade Level | Teachers | Administrators |

|---|---|---|

| Total Count | 166 | 112 |

| Elementary School | 44.0% | 35.7% |

| Middle School | 19.3% | 10.7% |

| High School | 36.7% | 53.6% |

Table 2

Comparison Between MVLRI SEL Study and Statewide Employment Statistics from Michigan Department of Education (Gender)

| Gender | Teachers Statewide (MDE) | Teachers MVLRI Study | Administrators Statewide (MDE) | Administrators MVLRI Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Count | 110,788 | 166 | 11,169 | 112 |

| Female | 77.2% | 81.9% | 54.4% | 53.6% |

| Male | 22.8% | 15.7% | 45.6% | 44.6% |

| Non-Binary | n/a | 0.6% | n/a | 0% |

| Prefer Not to Say | n/a | 1.8% | n/a | 1.8% |

Table 3

Comparison Between MVLRI SEL Study and Statewide Employment Statistics from Michigan Department of Education (Race and Ethnicity)

| Race and Ethnicity | Teachers Statewide (MDE) | Teachers MVLRI Study | Administrators Statewide (MDE) | Administrators MVLRI Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Count | 110,788 | 166 | 11,169 | 112 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.3% | 0% |

| Asian | 1.0% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 2.7% |

| African American or Black | 6.4% | 2.4% | 13.4% | 0.9% |

| Latino | 1.1% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 0% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0.1% | 0% | 0.1% | 0% |

| Two or More Races | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 0% |

| White | 90.9% | 90.4% | 84.3% | 91.1% |

| Prefer Not to Say | n/a | 4.2% | n/a | 4.5% |

Table 4

MVLRI SEL Study Participants (Years of Experience)

| Years of Experience | Teachers | Administrators |

|---|---|---|

| Total Count | 166 | 112 |

| 1-3 Years | 13.3% | 2.7% |

| 4-9 Years | 15.7% | 1.8% |

| 10-14 Years | 16.9% | 6.3% |

| 15-19 Years | 12.0% | 18.8% |

| 20+ Years | 42.2% | 70.5% |

| Prefer Not to Say | 0% | 0% |

Table 5

Michigan Department of Education (MDE) Statewide Teacher and Administrator Staffing (Years of Experience)

| Years of Experience | Teachers | Administrators |

|---|---|---|

| Total Count | 110,788 | 11,169 |

| 1-3 Years | 40% | 30.5% |

| 4-10 Years | 20.2% | 29.1% |

| 11-15 Years | 9.1% | 11.5% |

| 16-20 Years | 12.9% | 11.9% |

| 21+ Years | 17.9% | 17.0% |

Educators’ Modes of Instruction (Tables 6-7)

Table 6

Mode(s) of Instruction in Participants’ Schools or Districts, April 2020-April 2021 (Participants Could Check All That Applied)

| Mode of Instruction | Teachers | Administrators | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Count | 166 | 112 | 278 |

| In-Person | 57.2% | 65.2% | 60.4% |

| Hybrid | 54.2% | 46.4% | 51.1% |

| Online Synchronous | 26.5% | 25.0% | 25.9% |

| Online Asynchronous | 22.9% | 20.5% | 21.9% |

Table 7

Teachers’ Primary Modes of Instruction, April 2020-April 2021

| Mode of Instruction | Total Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| In-Person | 80 | 48.2% |

| Hybrid | 59 | 35.5% |

| Online Synchronous | 21 | 12.7% |

| Online Asynchronous | 6 | 3.6% |

Burnout and Emotional Labor Indicators (Tables 8-10)

Table 8

Percentage Responding “Yes” to Burnout Indicators (Self-Reports based on Last Month)

| Burnout Indicator | Teachers | Administrators | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Count | 166 | 112 | 278 |

| Have felt burned out from work | 83.1% | 85.7% | 84.2% |

| Have felt that all things they had to do were piling up so high that they could not overcome them | 65.7% | 73.2% | 68.7% |

| Have been bothered by feeling down, depressed, anxious, or hopeless | 71.1% | 64.2% | 68.3% |

| Have worried work has disconnected them emotionally | 60.8% | 66.1% | 62.9% |

| Physical health interfered with ability to do their work | 31.9% | 29.5% | 30.9% |

Table 9

Average Likert Scale Ratings for Burnout and Emotional Labor Indicators by Role

1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree

| Indicator | Teachers | Administrators | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Count | 166 | 112 | 278 |

| The work I do is meaningful to me | 4.58 | 4.61 | 4.59 |

| My work schedule leaves me enough time for my personal/family life | 3.04 | 2.54 | 2.83 |

| I feel comfortable showing a range of emotions in my job | 3.15 | 3.15 | 3.15 |

| I feel comfortable talking with someone at school if I need help | 3.43 | 3.23 | 3.35 |

Table 10

Average Likert Scale Ratings for Burnout and Emotional Labor Indicators by Gender

1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree

| Indicator | Female | Male | Non-Binary | Prefer Not to Say | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Count | 196 | 76 | 1 | 5 | 278 |

| The work I do is meaningful to me | 4.58 | 4.61 | 5.00 | 4.60 | 4.59 |

| My work schedule leaves me enough time for my personal/family life | 2.86 | 2.79 | 4.00 | 2.20 | 2.83 |

| I feel comfortable showing a range of emotions in my job | 3.08 | 3.38 | 2.00 | 2.60 | 3.15 |

| I feel comfortable talking with someone at school if I need help | 3.40 | 3.30 | 2.00 | 2.60 | 3.35 |

Social and Emotional Supports for Teachers and Administrators (Table 11)

Table 11

Social and Emotional Supports Offered Teachers and Administrators in Participants’ School or District (Participants Could Check All That Apply)

| Supports Offered | Teachers | Administrators | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Count | 166 | 112 | 278 |

| Extra planning/prep time | 30.1% | 43.8% | 35.6% |

| Counseling services | 23.5% | 42.9% | 31.3% |

| Mindfulness exercises (e.g., yoga, meditation, etc.) | 19.9% | 36.6% | 26.6% |

| None | 32.5% | 16.1% | 25.9% |

| Digital social events/happy hours | 15.7% | 30.4% | 21.6% |

| Self-care workshop/in-serve sessions | 14.5% | 28.6% | 20.1% |

| Self-care apps (e.g., Calm app) | 9.0% | 23.2% | 14.7% |

| Physical activity (e.g., going for short walk) | 6.0% | 22.3% | 12.6% |

| Digital drop-in faculty/staff lounge | 7.8% | 8.9% | 8.3% |

| Social media groups | 4.2% | 10.7% | 6.8% |

| Other | 3.0% | 8.0% | 5.0% |

Roadblocks to Meeting SEL Needs (Tables 12-13)

Table 12

Top Roadblocks to Meeting SEL Needs Reported by Educators

| Roadblocks | Teachers | Administrators | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Count | 166 | 112 | 278 |

| Lack of time | 80.1% | 89.3% | 83.8% |

| Too many responsibilities to get my job done | 72.3% | 80.4% | 75.5% |

| Inability to socialize with my colleagues | 44.0% | 39.3% | 42.1% |

| SEL is not a priority in my school and/or district | 27.1% | 21.4% | 24.8% |

| Little to no SEL resources are provided so I don’t know where to look for help | 14.5% | 13.4% | 14.0% |

| Too expensive or costly to pursue SEL supports | 13.3% | 14.3% | 13.7% |

| Unable to take advantage of SEL supports because they are difficult to access (e.g., too far away, not reachable from home, etc. | 10.2% | 10.7% | 10.4% |

| Technology to work remotely | 13.3% | 1.8% | 8.6% |

| Too many SEL resources are provided so I don’t know where to start | 6.6% | 5.4% | 6.1% |

Table 13

Top Roadblocks to Meeting SEL Needs Reported by Teachers (Broken Down by Primary Mode of Instruction in 2020-21)

| Roadblocks | In-Person | Hybrid | Online Synchronous | Online Asynchronous | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Count | 80 | 59 | 21 | 6 | 166 |

| Lack of time | 73.8% | 88.1% | 76.2% | 100% | 80.1% |

| Too many responsibilities to get my job done | 68.8% | 74.6% | 81.0% | 66.7% | 72.3% |

| Inability to socialize with my colleagues | 43.8% | 37.3% | 52.4% | 83.3% | 44.0% |

| SEL is not a priority in my school and/or district | 35.0% | 22.0% | 0% | 0% | 27.1% |

| Little to no SEL resources are provided so I don’t know where to look for help | 11.3% | 11.9% | 28.6% | 33.3% | 14.5% |

| Technology to work remotely | 12.5% | 15.3% | 14.3% | 0% | 13.3% |

| Too expensive or costly to pursue SEL supports | 11.3% | 22.0% | 0% | 0% | 13.3% |

| Unable to take advantage of SEL supports because they are difficult to access (e.g., too far away, not reachable from home, etc. | 12.5% | 8.5% | 9.5% | 0% | 10.2% |

| Too many SEL resources are provided so I don’t know where to start | 5.0% | 8.5% | 9.5% | 0% | 6.6% |