Introduction

Professional Learning Services Study Purpose and Rationale

Michigan Virtual has made a commitment to increase the completion rate for Professional Learning courses which, as of fall 2023, is approximately 60%. Part of this effort requires developing a more comprehensive understanding of how educators progress through and utilize pedagogically focused PL courses and course materials. This research has two broad objectives: 1) to better understand commonalities among courses offered through Michigan Virtual, and 2) to comprehend educators’ engagement and navigation of PL courses. This includes understanding the types of courses educators are taking, engagement with course assignments, and length of time enrolled in the course. In doing so, Michigan Virtual will be able to make informed decisions about what course formats are most appropriate for the goals, objectives, and preferences of learners.

Michigan Virtual, through its Professional Learning Portal (PLP), offers over 300 courses for a diverse range of professionals. For the purposes of this study, only courses aimed at improving pedagogical skills and knowledge were included. Unless otherwise noted, any further reference to PL courses includes only those that are pedagogically focused.

What is Professional Learning?

Professional learning (PL) in education consists of opportunities (e.g., programs and classes) that aim to enhance teachers’ knowledge, pedagogical strategies, beliefs, or other characteristics that may be related to the quality of their teaching (Bowman et al., 2022; Gesel et al., 2021). PL typically targets three areas of teacher development: knowledge, skills, and beliefs (such as self-efficacy, or one’s belief in their abilities) (Gesel et al., 2021), and can occur in either in-person, virtual, or blended formats. PL may also include mandatory compliance-based classes that align with certain state or federal standards (e.g., FERPA).

Why is PL important?

PL is a vital part of educators’ journeys, offering them a pathway to remain connected to the field, a way to further their pedagogy and disciplinary knowledge (e.g., Burrows et al., 2021), meet the specific needs of their schools and students (Green & Harrington, 2022), and ensure the continued validity of their teaching licenses and certificates. As per Michigan Department of Education policy, educators must complete 150 State Continuing Education Clock Hours (SCECHs) of PL offered by approved sponsors to renew certificates and licenses (Michigan Department of Education, 2020). The importance of professional learning extends beyond a means to renew one’s certifications, however, as purposeful and sustained engagement in PL can positively impact student outcomes (Capraro et al., 2016; Gore et al., 2021; Roth et al., 2019).

How Are Educators Engaging with PL?

Given the importance and potential benefits of PL, it is necessary to understand how educators engage with PL. Recent data collected by the Professional Learning Services team at Michigan Virtual indicated that 60% of those taking PL through Michigan Virtual had a preference for online formats (Perez, Peck, & McGehee, 2023). Online PL allows external experts and facilitators to deliver PL, which 77% of those taking PL courses through Michigan Virtual prefer (Perez & Peck, 2023). According to Michigan Virtual’s Professional Learning Services team, many educators continue choosing PL delivered online because it is flexible, and they can work at their own pace (and on their schedule). Professional learning delivered online allows educators to expand their horizons without missing time in the classroom (Green, 2022). This may be particularly important as the National Standards for Online Teaching recommend that PL be timely and consistent (Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute, 2020). PL delivered online has the potential to be particularly engaging through increasing access (reaching rural areas, drawing on outside experts, targeting specific content areas), providing flexibility in terms of when and where teachers participate, lowering costs of participation, and potentially expanding teachers’ networks (as participation isn’t as geographically limited; Lay et al., 2020).

In addition to the delivery method, meaningful collaborative opportunities are also important. In a study examining PL for STEM teachers, Burrows et al., (2021) noted that teachers held positive perceptions of being able to interact with colleagues, and found that time spent collaborating on lesson plans was ‘very useful.’ Indeed, educators engaging with PL through Michigan Virtual noted that it was important for collaboration to be intentional. Educators preferred to be in small cohorts with sufficient time to share ideas, think, and work together (Perez & Peck, 2023). Facilitating interactions among PL attendees allows them to connect, brainstorm solutions to challenges, and see how other teachers, schools, and districts are serving students, which may inspire them to adapt or borrow ideas and take them back to their own classrooms. Collaborating with others can also help spur self-reflection, an important quality of effective PL. Reflection and feedback can work together within professional learning to help move teachers’ pedagogy forward (Darling-Hammond & Gardner, 2017).

The Current Study

Examining PL course offerings at Michigan Virtual can ensure that a wide range of topics and needs are addressed and that these courses engage a diverse range of educators. A better understanding of the cost, structure, and target audience of most PL courses can highlight gaps in offerings, and identify the extent to which there is alignment between current offerings and educator preferences.

This study additionally aimed to understand the needs, motivations, and engagement of educators in pedagogy/instruction-specific PL courses at Michigan Virtual because these courses can significantly impact teaching and benefit students. Understanding educators’ preferences and engagement with current PL offerings will allow for the continued refinement of professional learning course offerings at Michigan Virtual.

Another goal was to identify the topics covered in Professional Learning (PL) courses offered by Michigan Virtual, the needs met, and the range of educators involved. Data from the Professional Learning Portal was combined with survey responses from educators enrolled in PL courses at Michigan Virtual to gain a thorough understanding of their needs and motivations, as well as how they interact with professional learning courses. In light of these aims, the current study sought to answer the following:

- What types of courses are available on the Professional Learning Portal?

- How are educators engaging with PL courses?

- Are educators satisfied with the PL courses offered by Michigan Virtual?

A better understanding of the cost, structure, target audience, and how educators engage with professional learning courses can reveal gaps in offerings and alignment with preferences.

Methodology

Survey

Educators enrolled in PL courses at Michigan Virtual were provided with end-of-course surveys via Qualtrics Research Suite. End-of-course surveys assessed educators’ motivation for taking the course, satisfaction with and perceived utility of the course, the relevance of the course for their role, engagement with course activities, assignments, and features, questions specific to the course they enrolled in, and demographic information. Only questions about motivation and engagement were analyzed for this study.

Professional Learning Portal Data

Data from the Professional Learning Portal was obtained in the summer of 2023 for both the fall 2022 and spring 2023 semesters and included information on the courses educators enrolled in, course type, enrollment status, enrollment start, and end dates, number of submitted and total course assignments, and school demographic characteristics. Course type refers to whether the course counted towards educators’ professional learning hours required to renew Michigan certificates and licenses (SCECH) or not (Non-SCECH).

Schools were categorized as follows based on the percentage of learners who qualified for Free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL):

- Low (<=25%)

- Mid-Low (>25% to <=50%)

- Mid-High (>50% to <=75%)

- High (>75%)

Educators’ schools were also classified according to student demographics:

- Non-White School Population <=25%

- Non-White School Population >25% and <=50%

- Non-White School Population >50% and <=75%

- Non-White School Population >75%

Data Cleaning

Both the end-of-course survey data and the Professional Learning Portal data were analyzed in R (a free statistical computing environment). To refine analyses to be timely, included data points were restricted to the most recent academic year (fall 2022, spring 2023). Because the study’s aims focused on analyzing pedagogy-specific courses, courses that did meet that criterion were removed (e.g., CPR Refresher). In the analysis, about 58% (n = 119) of the courses from the survey data and 54% (n = 177) of the courses from the Professional Learning Portal dataset were included. The list of removed courses can be found in Appendixes A and B.

Results

What types of courses are available on the Professional Learning Portal?

The Professional Learning Portal provides educators with 381 courses to choose from, depending on their needs and preferences. The most highly enrolled pedagogical courses were ‘Differentiated Instruction: Maximizing Learning for All’ (n = 3,296), ‘Changing Minds to Address Poverty – Achievement Mindset’ (n = 2,901), and ‘Changing Minds to Address Poverty – Engagement Mindset’ (n = 2,192).

Across pedagogy-focused Professional Learning Portal courses, the average cost was $37.60 but ranged from 0 to $150. Educators have many cost-effective options, with half of the courses costing less than $5. Educators also have access to earn SCECHs through pedagogy-focused courses, with approximately 193 courses offering at least 1 SCECH. The average number of SCECHs offered is 8.5, with half of the courses offering more than 4 SCECHs. These courses are also able to be completed on the educators’ schedule as most (n = 172) are self-paced.

| Category | Sub-Category | # of Courses |

| Course Type | ||

| Self-Paced | 297 | |

| Lightly Facilitated | 43 | |

| Facilitated | 33 | |

| Blended | 8 | |

| Credit | ||

| SCECH | 250 | |

| Counselor | 6 | |

| Micro-credential | 14 | |

| Subject Area | ||

| Other | 67 | |

| Best Practices | 48 | |

| Teacher Advocacy | 48 | |

| Literacy | 38 | |

| Administration | 36 | |

| Blended & Online Learning | 35 | |

| Social & Emotional Learning | 33 | |

| Literacy Essentials | 32 | |

| Special Education | 31 | |

| Leadership | 30 | |

| Subject Area Specific | 30 | |

| Classroom Management | 29 | |

| Assessment | 27 | |

| Early Childhood | 27 | |

| Compliance | 25 | |

| Counseling | 16 | |

| Evaluation | 12 | |

| School Safety | 9 |

How are educators engaging with PLS courses?

Does Enrollment in SCECH Courses Vary by Economic and School Diversity Categories?

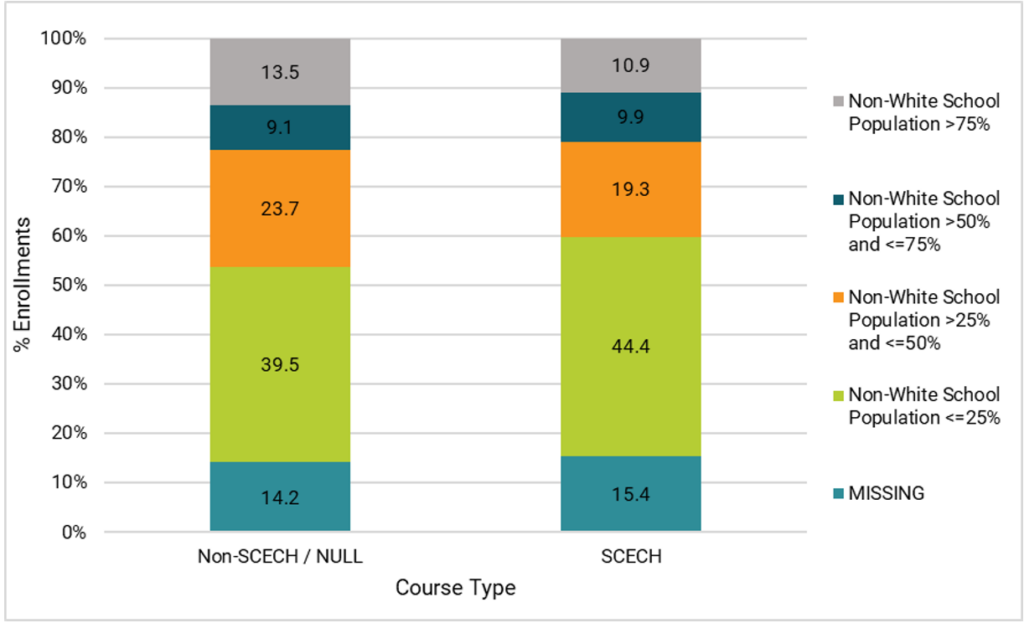

Approximately 13.5% (n = 8,716) of the 64,714 total enrollments were for SCECH courses. Educators from schools where the Non-White student population was =<25% made up most of the enrollments in both SCECH (44.4%) and non-SCECH (39.5%) courses. Conversely, educators from schools where the non-White student population was between 50 and 75% made up the fewest enrollments across the board, followed closely by those from schools with a non-White student population of >75%. Figure 1 shows the composition of SCECH and non-SCECH enrollments.

For additional context, educators from schools with a non-White student population exceeding 50-75% and 75% constituted the smallest percentage of total enrollments. However, when examining district-level data, these educators were well represented by Michigan Virtual. In districts with a non-White student population between 50% and 75%, Michigan Virtual served all 100% of LEA Districts, reaching approximately 30 educators per 100 staff. For districts with a non-White student population exceeding 75%, Michigan Virtual covered 95 per 100 districts, equating to about 52 educators per 100 staff.

Similarly, in PSA districts, Michigan Virtual served 88 per 100 districts with a non-White student population between 50% and 75%, providing around 36 enrollments per 100 staff. In districts where the non-White student population exceeded 75%, Michigan Virtual covered 94 out of 100 PSA districts, representing about 50 enrollments per 100 PSA staff. Taken together, Michigan Virtual served relatively similar numbers of educators in LEA districts with varying percentages of non-White student populations, except districts where the non-White student population was >75% had approximately 21 more educator enrollments per 100 staff. Compared to LEA districts, enrollments varied by district more so for PSAs with the highest number of educators served coming from districts where the non-White student population was >25% and <=50%, and >75%.

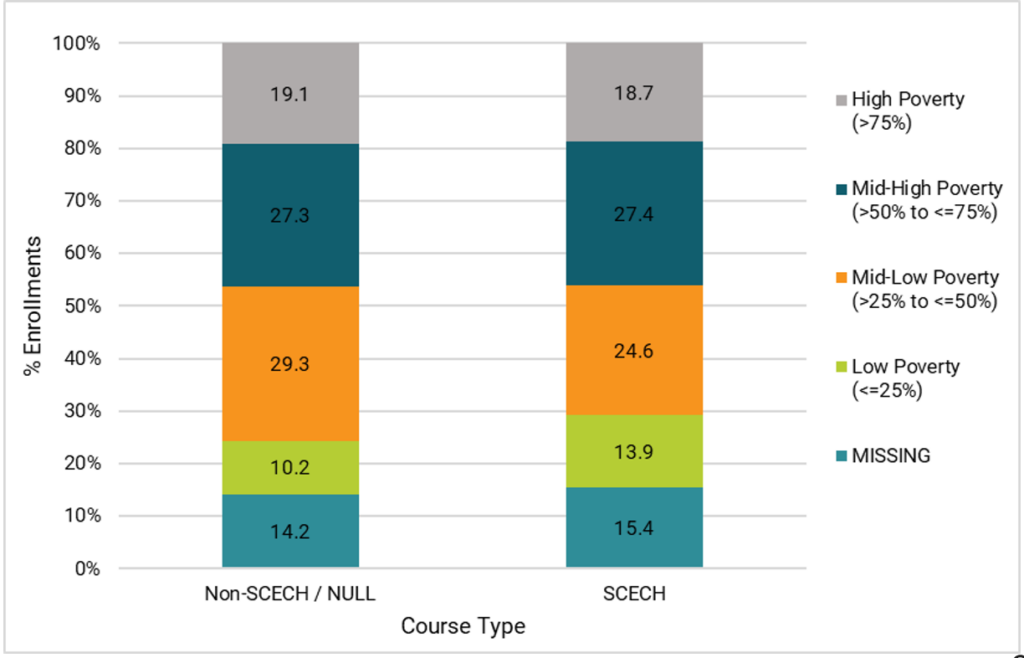

Educators from schools where between 25 and 50% of students qualified for free and reduced-price lunch (FRPL) represented the most enrollments for non-SCECH courses (29.3%), followed closely by educators from schools where between 50 and 75% of students qualified for FRPL (27.3%). The reverse emerges for SCECH enrollments wherein educators from schools where between 50 and 75% of students qualified for FRPL represent the most enrollments (27.4%), closely followed by those from schools where between 25 and 50% of students qualified for FRPL (24.6%). Figure 2 highlights these enrollments.

It should be noted that while educators from schools where <=25% of students receive FRPL made up the smallest percentage of enrollments, these educators are represented well at the distinct level in regard to enrollments with MV. Michigan Virtual served 100% of LEA Districts where <25% of students receive FRPL, and reached approximately 18 educators per 100 staff. For PSAs, Michigan Virtual served 82 out of 100 PSA districts where <25% of students received Free-Reduced Price Lunch, serving about 19 educators per 100 staff. Across all district types, MV served more educators per 100 staff in districts where >75% of students received FRPL compared to other FRPL categories. For instance, in ISD where >75% of students received FRPL Michigan Virtual served 21 educators per 100 staff. In LEA where >75% of students received FRPL MV served 48 educators per 100 staff. In PSA Michigan Virtual served 58 educators per 100 staff.

Does Enrollment Status Vary by Course Type?

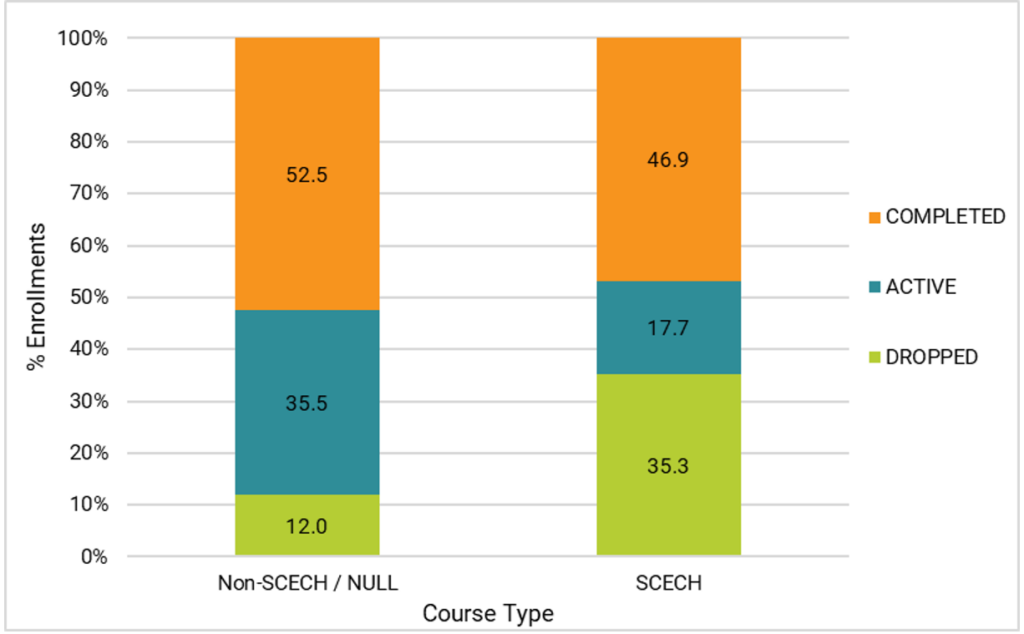

Just over half of all course enrollments were completed (51.8%), and 15.1% were dropped. Approximately 33% of all courses were currently active, indicating that educators were in the process of completing the course at the time of analysis. Completion rates for non-SCECH (52.5%) and SCECH (46.9%) courses were fairly similar, with around half of these courses being marked as complete. One of the main differences, however, was that approximately 12% of non-SCECH courses were dropped which was significantly lower than the drop rate for SCECH courses (approximately 35%). Educators can drop a course by using the ‘unenroll’ button within the PLP. In order to receive a refund, educators must unenroll within 24 hours of registering for a course.

It’s important to highlight a noteworthy correlation (r = .58) observed between educators’ course load and the frequency of course drops. A correlation of .58 is considered relatively strong, indicating that as educators take on more courses, their number of drops tends to increase, and conversely, as they reduce their course load, the number of drops tends to decrease. This pattern suggests that educators might initially enroll in a higher number of courses, later refining their selection based on factors like interest, time constraints, or other considerations. In other words, the number of dropped courses may reflect educators’ course selection process rather than their engagement level. Conversely, those who enroll in fewer courses may exhibit a lower likelihood of dropping them, possibly due to a more curated approach to enrollment.

Does Time Spent Enrolled in a Course Vary by Course Type?

Generally, educators spent approximately 28 days enrolled in PL courses (M = 28.0, SD = 43.9). The length of enrollment varied considerably from 0 days to 249 days. Due to the variability in enrollment length, the median may provide an estimate less biased by outliers. Half of educators were enrolled in courses for less than 5 days and half for more than 5 days. On average, those enrolled in SCECH courses spent approximately 53 days in their courses, whereas those in non-SCECH courses spent approximately 23 days. Individuals pursuing a SCECH spent more time enrolled in their courses relative to those taking non-SCECH courses. Understanding how much time educators spend in MV courses is essential for positive student achievement outcomes, based on previous research (Yoon et al., 2007). While the current data does not allow for the ability to determine how much of educators’ enrollment time was spent engaged with the course (interacting with content), this represents an important consideration for future research.

There was a moderate correlation between the length of time spent enrolled in the course and the proportion of completed assignments r(39,899) = -.55, p < .001. This means that as educators’ time enrolled in the course increased, their proportion of completed assignments decreased (and vice versa). Although this data and analysis cannot establish the reason for this correlation, educators who remain enrolled in courses for extended periods may become disengaged for various reasons, leading to fewer completed assignments. Conversely, educators who have difficulty completing assignments within the expected timeframe may remain enrolled in the course for longer but may not catch up. Research on students’ behaviors within online courses highlights the importance of pacing (consistent and timely movement through an online course) as crucial for success (DeBruler, 2021; Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute, 2019). It is reasonable to hypothesize that this may apply to adult learners as well (e.g., Ihantola et al., 2020). Gaining a better understanding of the relationship between time spent enrolled in a course and the number of completed assignments likely represents an important area of future research. This finding may also be an important piece of the puzzle regarding the higher drop rates of SCECH courses. This research shows that as educators spend more time in their SCECH courses, they are increasingly less likely to complete assignments. This information may be valuable for coordinating outreach efforts.

How Did Educators Engage with Course Assignments?

The percentage of completed assignments (all graded items) was determined by examining how many assignments were completed compared to how many were offered in the course. This number was then converted to a percentage. On average, educators completed about 47% of their assignments. Notably, about half of the enrollees failed to complete more than 50% of the courses’ assignments. Additionally, the percentage of completed assignments varied by course type with educators in non-SCECH courses completing more assignments than their peers enrolled in SCECH courses (47.9% for non-SCECH courses compared to 41.6% for SCECH courses).

There were differences in the average number of dropped courses based on the start date of enrollment. Fall (September through November) had the highest number of dropped courses (9.71) on average, while Summer had the fewest (1.12). At the course level, enrollments starting in the Fall (50.32%) had a greater proportion of completed assignments than Summer (29.43%). Differences in completion rates based on the season may reflect teachers’ needs and reasons for enrollment. License and certificate renewals may be more pressing in the summer, and thus, completing such courses is more of a priority than it is in the fall. Educators may also have more bandwidth for completing PD during the summer months, relative to the fall.

Another variable was created to identify the proportion of educators who had completed at least 80% of all assignments available in their courses (Assignment Threshold). The total number of educators who met the assignment threshold was 41.4%. This did seem to vary by SCECH status, with 42.1% of non-SCECH courses meeting the threshold compared to 36.6% of SCECH courses. Taken together, it seems that educators enrolled in non-SCECH courses typically outperform those in SCECH courses in terms of completed assignments.

Educators whose enrollment status was ‘complete’ averaged a higher proportion of completed course assignments (approximately 85%), compared to those who dropped the course (approximately 6%). Even those currently enrolled in a course completed a higher proportion of course assignments (approximately 7%) than those who dropped the course. A notably higher percentage of educators (77.6%) met the assignment threshold upon completing their course, while a smaller percentage of those currently enrolled (2.59%) or those who had dropped (2.37%) met the threshold of 80% of course assignments completed. Taken together, the findings about enrollment status and completed assignments are intuitive – those who complete their courses complete a higher proportion of the courses’ assignments. However, these findings could point to underlying factors distinguishing “completers” from “non-completers.” Educators who complete their courses have different motivations than those who drop – and these motivations push them to thoroughly engage with course assignments.

Are Educators Satisfied with the Courses Offered by PLS?

What Proportion of Educators are Satisfied with their Courses?

The end-of-course survey asked educators if they were ‘highly satisfied’ with their course, and most educators (95%) indicated ‘yes.’ Examining a random portion of open-ended responses detailing the reasons for educators’ satisfaction with their courses revealed five main themes: resources, pacing, specific course features or design elements, specific information or content, and organization.

| Theme | Example |

| Resources | A lot of resources and the ability to download the material so that I can continue to access it. |

| Pacing | A self-paced format allowed me to work through the information in a way that worked best for me. |

| Specific Course Feature or Design Element | I best enjoyed the interactive slides. Playing the games helped with learning. |

| Specific Information or Content | The content applied to what I need in terms of understanding the educator evaluation process |

| Organization | A lot of information was presented and organized that was easy to understand. |

Overall, educators seemed satisfied with their courses because of the course design, the information being useful or meeting a specific need, the ability to revisit material and move through the course at an individualized pace, the clear progression of content, and the plethora of practical and accessible resources. Table 2 provides examples of each theme.

Examining open-ended responses detailing the reasons why educators were not highly satisfied with their courses revealed eight themes: satisfaction, layout, glitches-certifications, glitches-broken links, glitches-survey, content, assessments, and time/duration. These themes are highlighted in Table 3.

| Theme | Example |

| Satisfaction | I was satisfied, but not highly satisfied. |

| Layout | I don’t know if it’s the layout of the course or what that is confusing to me. |

| Glitches – Certificate | There are so many glitches that I do not have all of my certificates yet |

| Glitches – Broken Links | Many of the links to articles were broken and unable to be looked at |

| Glitches – Survey | I got to the end of the course and it said I completed the final reflection, only I didn’t get notification the course was complete. … I had a heck of a time figuring out what I still needed to do. … I am thinking it was the perception survey that needed to be complete that allowed the course to be completed. I wish this had somehow been more clear to me … |

| Content | It seemed like the information barely scratched the surface of teacher burnout and, while it offered “solutions,” did not mention how to really make these solutions work if the teacher is unreasonably overloaded at work. |

| Assessments | The review questions or tasks were often worded in a confusing or too general way, which made it challenging to understand what exactly was being asked. |

| Time/Duration | Way too long for the course. It should be shorter and more concise. |

Responses indicated that the course layout was confusing or inaccessible to some educators which led to dissatisfaction with the course overall. Educators also reported that some course elements were overrepresented in the course and were not sufficiently engaging. Similarly, technical glitches were a source of concern among multiple educators. The most commonly reported glitches included not receiving email confirmation of course completion or course certificates, broken or slow links, and difficulty finding the perception survey.

Educators expressed a wide range of opinions regarding course content. While some believed the content “barely scratched the surface,” others believed the courses should “narrow down [the] information.” Among dissatisfied educators there was consistency regarding the belief that assessments (quizzes, activities, etc.) were confusing or not engaging. This again may provide important information about drop rates. If some courses have assignments that are more difficult or confusing than others, or if certain types of classes are more prone to technical glitches, this frustration may result in educators spending more time in the course (trying to resolve the issues) but ultimately not completing them. Future work should examine the assignments in SCECH compared to non-SCECH courses. Some educators expressed that the length of the course made it difficult to fit into their schedules. Finally, some educators reported being satisfied just not highly satisfied with their courses.

Does Educators’ Satisfaction Vary by their Motivation for Enrolling in the Course?

According to end-of-course survey results, the main reason educators enrolled in their respective PL courses was because it was required (42.8%). The least commonly reported reason for course enrollment was recommendations (6.8%). Table 4 shows the reasons educators enrolled in PL courses with Michigan Virtual.

| Motivation for Course Enrollment | N (%) |

| Required professional development | 34,215 (42.80%) |

| Free or inexpensive SCECHs | 13,487 (16.90%) |

| Content Addresses Specific Classroom or Professional Needs | 11,172 (14.00%) |

| Renewing my teacher certificate | 9,462 (11.80%) |

| I enjoy learning | 6,242 (7.80%) |

| The course was recommended to me | 5,456 (6.80%) |

Both satisfied (43.5%) and unsatisfied (59.1%) educators reported enrolling primarily due to the PL requirement imposed by their school or district. However, it’s worth noting that nearly twice as many satisfied individuals (compared to unsatisfied ones) indicated that they also enrolled because they ‘enjoy learning.’ These percentages stress the importance of providing educators with choice in their PL, allowing them to engage with topics that interest them and meaningfully contribute to their growth.

What Aspects of the Course are Most and Least Engaging and Helpful for Educators?

Educators were asked to indicate if they found specific course elements engaging or helpful. Educators largely agreed that audio/visual course elements were engaging. Course readings and quizzes were chosen by educators as helpful for learning. Audio/visual course elements and course readings were the most highly selected for being both engaging and helpful for learning. Discussion boards, however, were perceived as not engaging or helpful for learning. This aligns with what Perez, Peck, & McGehee (2023) found in their survey of educators enrolled in PLS courses, where respondents had a stronger preference for lecture-based learning than dialogic learning.

Conclusions

Most PL courses taken by educators during the fall 2022 semester and spring 2023 semester were non-SCECH bearing, meaning that they did not count toward educators’ license renewal or recertifications. However, the most frequently reported motivation for taking professional learning courses was that it was required (42.8%). Thus, while educators might not be taking courses to satisfy state standards, their enrollment is likely driven by their local school administrators. Interestingly, among those who reported being unsatisfied with their course, 59.1% reported enrolling because it was required. While it is unclear if the requirement refers to a specific course or PL more broadly, this perhaps highlights the importance of affording educators with some degree of agency over their learning.

While the overall completion rate for courses was just above 50%, SCECH courses had a lower completion rate (47.4%) than non-SCECH courses (52.5%). Along the same vein, SCECH courses had a higher drop rate (34.9%) than non-SCECH courses (11.9%). This suggests that SCECH courses could be bringing down the overall completion rate for PL courses. Future research should closely examine similarities and differences in the composition, features, characteristics, and requirements of SCECH and non-SCECH courses to identify elements that may be creating difficulties for educators. Despite spending more time enrolled in SCECH courses, educators completed fewer assignments. Perhaps educators perceive assignments in SCECH courses as more challenging, lengthier, or less engaging or helpful for learning. Motivation for enrollment could also play an important role in assignment completion. Compliance courses (required training by Michigan schools) do not always provide educators with SCECHs. As such, educators may be attempting to “check a box” by moving through compliance courses quickly and completing the necessary assignments. In all, educators may be very intentional about these enrollments and ensuring they are completed. Similarly, it is possible that educators enroll in a course with the desire to obtain specific information or resources, and thus, exit or disengage from the course upon having that need met.

When asked to indicate if a variety of course elements were engaging or helpful, 11.6% deemed assignments ‘not engaging or helpful for learning,’ while a smaller percentage indicated that they were both helpful and engaging (9.0%). To this end, a better understanding of educators’ engagement and perceptions of course assignments may help clarify low assignment and course completion rates.

Overall, non-SCECH courses seem to make up the bulk of PL enrollments and the most common reason for enrollment is that the PL is required. While most educators were highly satisfied with their experience, those that were not were more likely to report taking the course because it was required. This perhaps points to the importance of voice and choice in educators’ experiences with PL. Finally, those enrolled for SCECHs completed fewer assignments than their non-SCECH counterparts. Better understanding the reason behind the lack of engagement with course assignments in SCECH courses may help improve completion rates.

References

Bowman, M. A., Vongkulluksn, V.W., Jiang, Z., & Xie, K. (2022). Teachers’ exposure to professional development and the quality of their instructional technology use: The mediating role of teachers’ value and ability beliefs. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(2), 188-204, https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1830895

Burrows, A. C., Borowczak, M., Myers, A., Schwortz, A. C., & McKim, C. (2021). Integrated STEM for teacher professional learning and development: “I Need Time for Practice”. Education Sciences, 11(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11010021

Capraro, R. M., Capraro, M. M., Scheurich, J. J., Jones, M., Morgan, J., Huggins, K. S., Corlu, S.M, Younes, R., & Han, S. (2016). Impact of sustained professional development in STEM on outcome measures in a diverse urban district. The Journal of Educational Research, 109(2), 181-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.936997

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., Gardner, M. (2017). Effective Teacher Professional Development. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. This report can be found online at https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/teacher-prof-dev.

DeBruler, K. (2021). Research On K-12 Online Best Practices. Michigan Virtual. https://michiganvirtual.org/blog/research-on-k-12-online-best-practices/

Gesel, S. A., LeJeune, L. M., Chow, J. C., Sinclair, A. C., & Lemons, C. J. (2021). A meta-analysis of the impact of professional development on teachers’ knowledge, skill, and self-efficacy in data-based decision-making. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 54(4), 269-283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219420970196

Gore, J. M., Miller, A., Fray, L., Harris, J., & Prieto, E. (2021). Improving student achievement through professional development: Results from a randomized controlled trial of Quality Teaching Rounds. Teaching and Teacher Education, 101, 103297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103297

Green, C. (2022). Modernizing Professional Learning, Modeling Effective Practices For Student-Centered Learning. Michigan Virtual. Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/blog/modernizing-professional-learning/

Green, C. & Harrington, C. (2022). Empowering Teachers and Capturing Kids’ Hearts®: The Public Schools of Calumet, Laurium, and Keweenaw’s Journey Toward Student-Centered Learning. Michigan Virtual. Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/research/publications/public-schools-of-clk-student-centered-learning/

Ihantola, P., Fronza, I., Mikkonen, T., Noponen, M., & Hellas, A. (2020, October). Deadlines and MOOCs: how do students behave in MOOCs with and without deadlines. In 2020 IEEE Frontiers in education conference (FIE) (pp. 1-9). IEEE. doi: 10.1109/FIE44824.2020.9274023.

Kennedy, K., & Archambault, L. (2012). Offering preservice teachers field experiences in K-12 online learning: A national survey of teacher education programs. Journal of Teacher Education, 63(3), 185-200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487111433651

Lay, C. D., Allman, B., Cutri, R. M., & Kimmons, R. (2020). Examining a decade of research in online teacher professional development. Frontiers in Education, 5, 573129. Frontiers Media SA. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.573129

Leary, H., Dopp, C., Turley, C., Cheney, M., Simmons, Z., Graham, C. R., & Hatch, R. (2020). Professional Development for Online Teaching: A Literature Review. Online Learning, 24(4), 254-275. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1277716

Michigan Department of Education. State Continuing Education Clock (SCECH) Overview. Michigan Department of Education.

Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute. (2019). Pacing Guide For Success In Online Mathematics Courses. https://michiganvirtual.org/blog/pacing-guide-for-success-in-online-mathematics-courses/

Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute. (2020). Online Teachers NEED Ongoing Professional Development. https://michiganvirtual.org/blog/why-online-teachers-need-ongoing-professional-development/

National Standards for Quality. (n.d.). https://www.nsqol.org/the-standards/quality-online-teaching/

Perez, A., Peck, D., & McGehee, N. (2023). Educators Talked, We Listened: Professional Learning Survey Results. Michigan Virtual.

Perez, A., & Peck, D. (2023). Educators Talked, We Listened. Presentation for Michigan Virtual.

Roth, K. J., Wilson, C. D., Taylor, J. A., Stuhlsatz, M. A., & Hvidsten, C. (2019). Comparing the effects of analysis-of-practice and content-based professional development on teacher and student outcomes in science. American Educational Research Journal, 56(4), 1217-1253. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831218814759

Yoon, K. S., Duncan, T., Lee, S. W.-Y., Scarloss, B., & Shapley, K. (2007). Reviewing the evidence on how teacher professional development affects student achievement (Issues & Answers Report, REL 2007–No. 033). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs

Appendix A – Excluded Courses (End of Course Survey)

- #GoOpen: Open Educational Resources in Michigan

- Achieving Success with Difficult People

- Adolescent Suicide Prevention: Best Practices – A Team Approach

- Adolescent Suicide Prevention: Information for the General Public

- Adolescent Suicide Prevention: Intervention & School Policies

- Adolescent Suicide Prevention: Peer-to-Peer Support

- Anti-Racism and Social Justice Teaching and Leadership

- Anti-Racist Trauma-Informed Practice in Pre-K-12 Education

- Applied Behavior Analysis in Schools

- Basic First Aid

- Bloodborne Pathogens

- Building Teams That Work

- Career Counseling: Building a Resume

- Certificate in Healing Environments for Body, Mind, and Spirit

- Certificate in Mindful Relationships

- Certificate in Stress Management

- College Counseling: Building a College List

- College Counseling: Developing College Counseling Curriculum

- College Counseling: Effective Meetings with Juniors

- College Counseling: Relationships with Admissions Officers

- College Counseling: Start Early with 9-10 Graders

- College Counseling: The College Selection Process

- College Counseling: Writing Effective Counselor Letters

- Conflict Resolution Strategies

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) Prevention in the Workplace

- Coronavirus Prevention Course

- CPR Refresher

- Discipline Protections for Students with a Disability

- Discrimination in the Workplace

- Diversity in the Workplace

- DLN: A Practical Approach to Working with NWEA Data

- DLN: Creating a Data Driven Culture

- DLN: Implementing Official SAT Practice on Khan Academy in Your School

- DLN: School Culture: Creating an Inclusive Learning Environment

- DLN: School Safety Best Practices

- DLN: Strategies for Using SAT Suite Data in Schools

- DLN: Trauma Informed Schools: A Whole School Approach

- DLN: Using AP Potential for Opportunity and Access

- DLN: Using Surveys For Feedback

- Family-School Partnerships for Students with Disabilities

- FERPA – Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act

- Fire Safety

- Flu Symptoms and Prevention Strategies

- Food Safety

- Fundamentals of Supervision and Management

- Get Assertive!

- HIPAA Compliance Training

- IEP Boot Camp: Transition Age Students

- IEP Boot Camp: Writing Meaningful and Compliant IEPs

- Individual Excellence

- Interpersonal Communication

- Introduction to Java Programming

- Introduction to Programming

- Introduction to Windows 10

- Keys to Effective Communication

- MDE Assessment Security

- MDE Assessment Security 2022/2023

- MDE: Introduction to Data Use & Action Process

- MI-Access Training: Participation and Scoring Administration

- Michigan Ongoing Health & Safety Training Refresher 2023

- Michigan Virtual Special Education Support

- Personal Finance

- PTL: Module 1

- PTL: Module 2

- PTL: Module 3

- PTL: Module 4

- PTL: Module 5

- PTL: Module 6

- PTL: Module 7

- PTL: Module 8

- Reaching Your Potential through Self-Advocacy

- Responsive Web Design

- Run, Hide, Fight

- Seclusion and Restraint

- Sexual Harassment and Discrimination for Employees

- Social Intervention for Elementary Students with ASD

- Solving Classroom Discipline Problems

- Solving Classroom Discipline Problems II

- SRO2: Teaming and Collaborative Data-based Problem Solving

- SRO6: Self-Care and Wellness

- Survival Kit for New Teachers

- Take Care of Yourself: A Course in Well-Being and Self-Care

- Teaching Transitioning Skills to Students with Disabilities

- Understanding Adolescents

- Understanding the Modern Military

- Violence in the Workplace

- Creating Classroom Centers

- ChatGPT for Educators: An Introduction

Appendix B – Excluded Courses (PLP Data)

- #GoOpen: Open Educational Resources in Michigan

- 5D/D+ Professional Collaboration & Communication

- A to Z Grant Writing

- Achieving Success with Difficult People

- Adolescent Suicide Prevention: Best Practices – A Team Approach

- Adolescent Suicide Prevention: Information for the General Public

- Adolescent Suicide Prevention: Intervention & School Policies

- Adolescent Suicide Prevention: Peer to Peer Support

- Advanced Grant Proposal Writing

- Advanced Microsoft Excel 2019/Office 365

- Anti-Racism and Social Justice Teaching and Leadership

- Anti-Racist Trauma-Informed Practice in Pre K-12 Education

- Applied Behavior Analysis in Schools

- Basic First Aid

- Blockchain Fundamentals

- Bloodborne Pathogens

- Building Teams That Work

- Career Counseling: Building a Resume

- Certificate in Healing Environments for Body, Mind, and Spirit

- Certificate in Integrative Behavioral Health

- Certificate in Meditation

- Certificate in Mindful Relationships

- Certificate in Mindfulness

- Certificate in Nutrition, Chronic Disease, and Health Promotion

- Certificate in Stress Management

- College Counseling: Building a College List

- College Counseling: Developing College Counseling Curriculum

- College Counseling: Effective Meetings with Juniors

- College Counseling: Relationships with Admissions Officers

- College Counseling: Start Early with 9-10 Graders

- College Counseling: The College Selection Process

- College Counseling: Writing Effective Counselor Letters

- Conflict Resolution Strategies

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) Prevention in the Workplace

- Coronavirus Prevention Course

- Counseling for College Prep

- CPR Refresher

- Creating a Classroom Website

- Discipline Protections for Students with a Disability

- Discrimination in the Workplace

- Diversity in the Workplace

- DLN: A Practical Approach to Working with NWEA Data

- DLN: Administrator Simulator – Staff Accountability

- DLN: Administrator Simulator – Staff Social Media

- DLN: Administrator Simulator – Student Discipline

- DLN: Administrator Simulator – Title IX

- DLN: Disciplinary Literacy for Secondary Leaders

- DLN: Getting to Know the SAT Suite of Assessments

- DLN: Instructional Supervision in a Remote Environment

- DLN: Leading Collaborative Meetings in a Virtual World

- DLN: Project Gameplan – Keeping Compliant Scenarios

- DLN: Response to Intervention (RTI)

- DLN: School Law 101: What Principals Must Know

- DLN: School Safety Best Practices

- DLN: Strategies for Using SAT Suite Data in Schools’

- DLN: Using AP Potential for Opportunity and Access

- DLN: Using Surveys For Feedback

- Emergency Action Plans for Office Employees

- Emergency Response

- Exploring and Understanding Learner Agency

- Family-School Partnerships for Students with Disabilities

- FERPA – Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act

- Fire Safety

- Flu Symptoms and Prevention Strategies

- Food Safety

- Fundamentals of Supervision and Management

- Get Assertive!

- Get Grants!

- Hazard Communication

- Health & Safety for Licensed Child Care Providers, Module A

- Health & Safety for Licensed Child Care Providers, Module B

- Health & Safety for Licensed Child Care Providers, Module C

- HIPAA Compliance Training

- IEP Boot Camp: Transition Age Students

- IEP Boot Camp: Writing Meaningful and Compliant IEPs

- Individual Excellence

- Intermediate Microsoft Excel 2019/Office 365

- Interpersonal Communication

- Introduction to Artificial Intelligence

- Introduction to Database Development

- Introduction to Java Programming

- Introduction to Microsoft Excel 2019

- Introduction to OSHA

- Introduction to Programming

- Introduction to Python

- Introduction to Windows 10

- ISD Led Monitoring

- ISD Led Monitoring for SPP APR Indicators B-4, B-9, and B-10

- Keys to Effective Communication

- Landing the Job: Applications and Interviews for Educators

- Leadership

- MAC: Developing a High Quality Balanced Assessment System

- MAC: Making Meaning from Student Assessments

- MAC: Using Assessment Data Well

- Mastering Public Speaking

- MDE Assessment Security

- MDE Assessment Security 2022/2023

- MDE Facilitating Future Proud Michigan Educator: Explore

- MDE: Introduction to Data Use & Action Process

- MEMSPA: Braiding MTSS & SEL

- MI-Access Training: Participation and Scoring Administration

- Michigan Ongoing Health & Safety Training Refresher 2023

- Michigan Virtual Special Education Support

- Mindful Practices: Everyday SEL for Adults

- Occupational Safety and Health Programs

- Personal Finance

- PTL: Application

- PTL: Experience Based Internship

- PTL: Internship

- PTL: Modules 1-8

- PTL: Orientation

- Reaching Your Potential through Self-Advocacy

- Responsive Web Design

- Run, Hide, Fight

- Seclusion and Restraint

- Sexual Harassment and Discrimination for Employees

- So You Want to be an Instructional Designer?

- Social Intervention for Elementary Students with ASD

- Solving Classroom Discipline Problems II

- SRO6: Self-Care and Wellness

- Start Your Own Edible Garden

- Take Care of Yourself: A Course in Well-Being and Self-Care

- Teacher+: Professional Collaboration & Communication (Self-Paced)

- Teaching Transitioning Skills to Students with Disabilities

- Title IX/Sexual Misconduct at Educational Facilities

- Transportation Training for Licensed Child Care Providers

- Understanding the Modern Military

- Violence in the Workplace