Authors

Yining Zhang

Michigan State University

Chin-Hsi Lin

The University of Hong Kong

In recent years, online courses have become a major alternative method for at-risk students’ credit recovery (CR) efforts. According to a report released by the International Association for K-12 Online Learning (iNACOL), CR has become a major reason for students to choose online learning (Powell, Roberts, & Patrick, 2015). How do CR students perceive their online learning differently than students who enroll in courses for non-credit recovery (NCR) purposes? Specifically, how do they differ when perceiving their interactions and communications in the online learning environment, and how does their perception of communication relate to some of the learning outcomes?

Before answering these questions, we want to first define some constructs that we used in this study.

Social presence. Social presence is the degree to which the learner creates personal but purposeful relationships and develops social bonds in his/her learning context (Anderson, Liam, Garrison, & Archer, 2001). Ideally, social presence operates to create open and comfortable conditions for students’ inquiry and their high-quality interaction with other parties in the service of a wider educational goal (Anderson et al., 2001).

Self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is defined as “people’s judgments of their capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to attain designated types of performances. It is concerned not with the skills one has but with the judgments of what one can do with whatever skills one possesses” (Bandura, 1986, p. 391).

What does social presence look like in CR and NCR students?

With the help of Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute®, we conducted a survey among Michigan Virtual School® (now known as Michigan Virtual™) students who were enrolled in spring 2017. A total of 1,461 students participated in our study via an online survey. About 69.9% of the participants were female (N = 1,021) and 29.8% were male (N = 436). Most of the participants were 12th graders (N = 668, 45.7%), followed by 11th graders (N = 325, 22.2%), 10th graders (N = 273, 18.7%), 9th graders (N = 122, 8.4%), 8th graders (N = 57, 3.9%), and 7th graders (N = 12, 0.8%).

The virtual school subjects that the participants were enrolled in included Foreign Languages (29.0%), Science (15.5%), Social Studies (13.3%), Math (11.0%), English (7.9%), and others (22.9%). Four students did not report the subjects of the online courses they were taking. Most participants were enrolled in courses for reasons other than CR (N = 1,356; 92.8%) and around 6.0% of them (N = 87) for CR purposes, while 18 respondents did not answer this question.

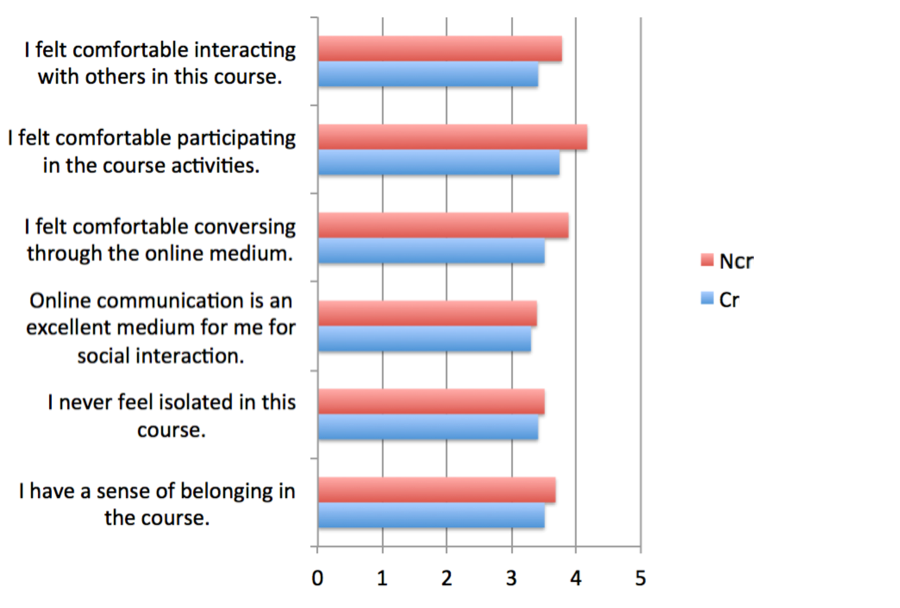

We first looked at the difference of social presence between CR and NCR students. Social presence was measured based on two dimensions: affective expression and open communication. Affective expression includes three questions: I have a sense of belonging in the course; I never feel isolated in this course; and online communication is an excellent medium for me for social interaction. Open communication includes I felt comfortable conversing through the online medium; I felt comfortable participating in the course activities; I felt comfortable interacting with others in this course.

The following chart shows the statistical difference (p < .001) on each question between the two groups of students.

In summation, CR students showed statistically lower social presence on all six sub-scales compared with NCR students. Specifically, CR students showed statistically lower affective communication when we asked whether they felt comfortable interacting with others in this course, whether they felt comfortable participating in the course activities, and whether they felt comfortable conversing through the online medium.

What does self-efficacy look like in CR and NCR students?

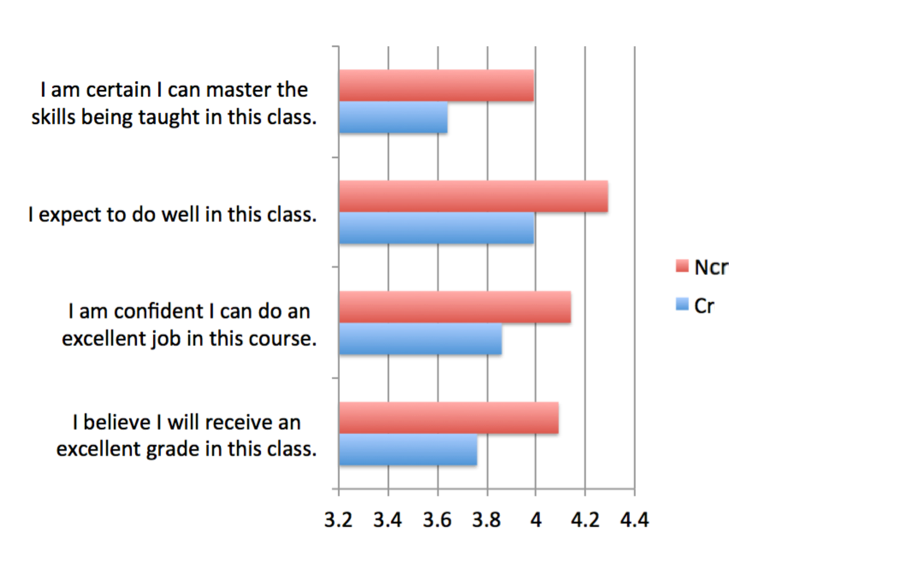

Self-efficacy in this study included four items: I believe I will receive an excellent grade in this class; I am confident I can do an excellent job in this course; I expect to do well in this class; I am certain I can master the skills being taught in this class.

The following chart shows the statistical difference on each question between the two groups of students.

In summation, CR students showed lower self-efficacy in achieving success in their online classes, compared with NCR students. They did not feel confident in mastering the skills in class and did not expect to do well and receive an excellent grade.

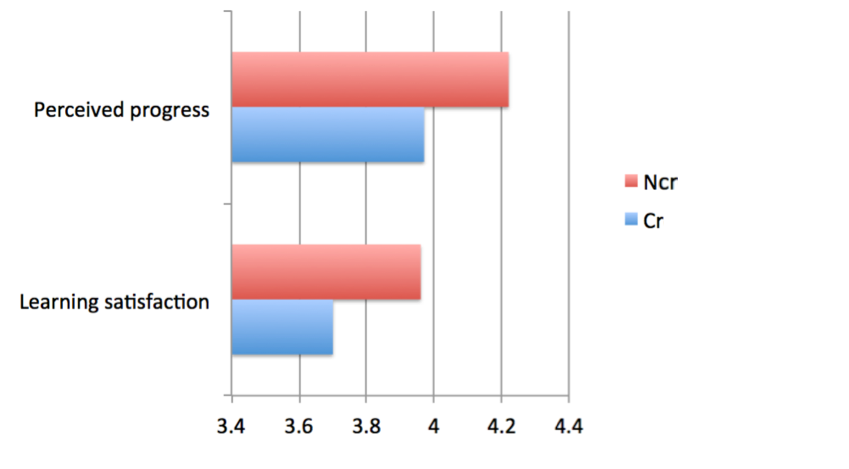

What does learning satisfaction and perceived progress look like in CR and NCR students?

We measured learning satisfaction and perceived progress as two learning outcomes. Again, the chart below suggested that CR students rated their learning satisfaction with and perceived progress in the course lower compared with NCR students.

What is the correlation between social presence and self-efficacy, social presence and learning satisfaction, and social presence and perceived progress with the two groups of students?

Social presence was calculated based on the average of the sum of all sub-scales of social presence. Self-efficacy was also calculated in the same way. The table below shows the correlations between the two groups of students. The correlation table suggests that the correlation between social presence and self-efficacy, between social presence and learning satisfaction, between social presence and perceived progress were higher for CR students, compared with NCR students. The correlation between social presence and self-efficacy is .69 for CR students, and .46 for NCR students. The correlation between social presence and learning satisfaction is .78 for CR students, and .60 for NCR students. The correlation between social presence and perceived progress is .71 for CR students, and .50 for NCR students.

| CR | NCR | |

| Social presence & self-efficacy | .69 | .46 |

| Social presence & learning satisfaction | .78 | .60 |

| Social presence & perceived progress | .71 | .50 |

In summation, social presence showed higher correlations with self-efficacy, learning satisfaction, and perceived progress among CR students than among other students. For example, when having the same level of social presence, a CR student would feel even more confident about his/her learning, compared with an NCR student. This suggested that a high social presence is particularly important for CR students in terms of promoting their learning self-efficacy, increasing their learning satisfaction, and increasing their perceived progress.

What does this study tell us?

Social presence describes the degree to which learners feel connected to others. This study shows the difference between CR and NCR students on social presence. Not surprisingly, CR students showed lower social presence on all aspects of measured social presence, compared with NCR students. When conducting correlations, we found that social presence is even more important for CR students, as when feeling a high sense of social presence, a CR student would show stronger self-efficacy, higher learning satisfaction, and higher perceived progress.

Because CR students face a variety of problems such as low academic achievement, low motivation, and limited Internet access in their day-to-day schooling (Ferdig, 2010; Oliver, Osborne & Brady, 2009; Watson & Gemin, 2008), giving them a sense of belonging and providing reassurance that they are not isolated can be more important to them than to others. Indeed, extra attention and support may play a pivotal role in making them feel they can succeed. Therefore, when CR students in an online learning experience feel a strong sense of belonging, they will likely be more confident that they can perform well (Oviatt, 2017).

Based on our findings, it is therefore important for practitioners to design and implement a learning environment with strong social presence when it is expected to serve a high proportion of CR students. Here are some tips to design a course with high social presence:

- Support a more collaborative and supportive learning community to let students feel they are not isolated online

- Establish relationships of trust with students to make them feel supported

- Convey motivational information when interacting with students to establish their self-efficacy

- Create various types of learner-learner interactions such as ice-breaker activities, synchronous discussions, or group projects to foster an active learning environment

- Schedule one-on-one meetings between teachers and CR students

References

Anderson, T., Liam, R., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teacher presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of the Asynchronous Learning Network, 5(2). Retrieved from http://auspace.athabascau.ca/handle/2149/725

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of social and clinical psychology, 4(3), 359-373.

Ferdig, R. E. (2010). Understanding the role and applicability of K-12 online learning to support student dropout recovery efforts. Lansing, MI: Michigan Virtual University. Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/DropoutRecoveryEfforts.pdf

Oliver, K., Osborne, J., & Brady, K. (2009). What are secondary students’ expectations for teachers in virtual school environments? Distance Education, 30(1), 23–45. doi: 10.1080/01587910902845923

Oviatt, D. R. (2017). Online Students’ Perceptions and Utilization of a Proximate Community of Engagement at an Online Independent Study Program (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Brigham Young University.

Powell, A., Roberts, V., & Patrick, S. (2015). Using online learning for credit recovery: Getting Back on track to graduation. Vienna, VA: iNACOL, The International Association for K–12 Online Learning. Retrieved from http://www.inacol.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/iNACOL_UsingOnlineLearningForCreditRecovery.pdf.

Watson, J., & Gemin, B. (2008). Promising practices in online learning: Using online learning for at-risk students and credit recovery. Vienna, VA: International Association for K-12 Online Learning.