Graduate and K-12 students engage in a new interactive learning experience combining the use of Minecraft, Wikispaces, webinars, and The Giver, by Lois Lowry

In the spring of 2014, I was fortunate enough to engage with Verena Roberts, Vicki Davis, and Colin Osterhout in a project that we dubbed #Gamifi-ED. This project involved my students in Alaska enrolled in EDET 668: Leadership in Educational Technology, and Vicki’s 9th-grade students in Camilla, Georgia9th-gradee enrolled in a Computer Literacy course. Verena’s contributed by scheduling and facilitating multiple webinars so that my graduate students and Vicki’s students could learn about Gaming and Education from experts in the field. Colin served as our technology engineer.

This was my first attempt at inter-generational, passion-based service learning. The experience took time and resources beyond my expectations. For example, I found myself meeting with small groups of students “on the fly” at their request on four of five days during the school week, and I found myself waking at 6:00 AM or working beyond 5:00 PM, even when I didn’t have classes, in order to attend or facilitate webinars. While all graduate and K-12 students learned from each other in the class, some had specific and necessary expertise beyond the rest of us. These students became co-facilitators in the experience. Google hangouts (chat and video) became both our friend and our greatest nemesis as the classroom expanded beyond a 50-minute slot three days a week to 24/7, on an as-needed on-demand basis for everyone involved. Any of us could organize and call a class meeting at any time, and many of us did. When the fall semester began, I decided to try to duplicate the learning experiences in #gamifi-ED at some level, using EDET 693: Gaming and Open Education.

I had a few goals for the new experience, which came to be named #givercraft. First, I wanted to identify a common framework between the two inter-generational passion-based service learning projects that could be the basis for a model for future classes. Second, I wanted to evaluate the impact of the project on my graduate students’ learning, and on the learning of the K-12 students involved and determine what the unique benefits of this model might be. Finally, I wanted to try to determine which aspects of theory might apply to this project. In the past, I had tried developing a project on an emerging theory, and it didn’t work very well. I wanted to work backward this time starting from a combination of what I believed philosophically and what would be practical and effective and try to determine how this fit into the theoretical whole.

As with #Gamifi-ED, there would be two levels of instructional design going on at once, and each of these required definitions and discrete goals. I was the designer for Level One. In Level One, graduate students enrolled in EDET 693 needed to demonstrate that they had met identified standards from ISTE for Technology Coaches (NETS-C; ISTE, 2011) through blogging and facilitation of the K-12 experience which made up Level Two. The ISTE NETS-C standards indicated graduate students needed to deepen their content and pedagogical knowledge. In addition, they needed to create a unit of instruction, including assessment instruments, and then model facilitation of this unit to other teachers. The design of the unit had to account for differentiation and had to allow students creativity and the ability to engage in critical thinking for decision-making. Finally, graduate students needed to model the use of technology for collaboration and communication. By design, the project would need to be both local and global, and the project itself had to be of importance in the real world to the K-12 teachers and students who would participate.

I planned for my graduate students to read and blog during the first eight weeks of the course to accomplish the pedagogical and content standards. I chose The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education by Kapp (2012) as a text. Graduate students would complete design of the unit through using the principles of Understanding by Design and planning Stages of Instruction (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005) due at intervals during the first nine weeks of the course. I planned for the facilitation of a K-12 OOC (Open Online Community) to account for the other standards. Graduate students would analyze the achievement of K-12 students in the OOC according to K-12 teacher surveys. Finally, they would use observation during their time within the game to determine engagement and achievement. Their final reflective paper required them to address and provide evidence that they had demonstrated all of the objectives for the class.

My graduate students were the designers for Level Two, and I needed to become a co-designer with them, rather than doing it all myself. So I set a very loose framework: in Level Two, K-12 students who registered for the OOC would interact and demonstrate competency through Minecraft and the use of a Wiki. The goal would be that K-12 students demonstrated proficiency in CCSS for building knowledge related to the Lois Lowry Novel, “The Giver.”

All went according to plan until I asked how many of my students had experience with Minecraft. Over half of my class had no experience in Minecraft at all and very little experience in gameplay. Therefore, I needed to provide experience and instruction in Minecraft for those members of my class who had never played, and I began to plan challenges to develop these skills. I also made the following assignment: Find a six-year-old and enlist that child to sit beside you as you play Minecraft.

Higher education students spent approximately 25 hours of assigned playtime in Minecraft in preparation for the K-12 student experience. Six hours of this 25 were assigned as “free play.” Nineteen hours of Minecraft play was scheduled for “group challenges”. During synchronous meetings, groups of students worked in Minecraft in order to meet goals that I set. Students seemed to gain skills more readily and feel more accomplished when the class was playing with or against each other in teams toward an established goal.

Higher education students took on various roles as the design of the K-12 experience was formed. One student took on responsibility for marketing and web publicity. Another took responsibility for setting meetings, as the project manager. Other roles included registrar, world designer, lead researcher, and curriculum designer. My primary role was to coordinate and nudge as needed, to oversee and document; however, I also became a Wiki page creator and password generator. None of these roles were any more important, and each of us spent an inordinate amount of time managing our respective duties. During the experience, while students noted with surprise and disbelief the number of hours the class was taking, none complained about the load. All took a great deal of pride in their own accomplishments and the accomplishments of others.

Finally, in the ninth week of the class, our K-12 OOC began. Because Vicki and Verena had both publicized the experience to their networks, we had a huge response to the invitation to join. We capped registration at just over 1,200 students and 50 teachers. Due to technology issues with incompatible devices such as iPads or Chromebooks, filtering settings, incompatible Java versions, or network setup, several of these classes withdrew prior to its start. We began the experience with just over 800 students and 22 teachers. During the experience, we lost two teachers’ classrooms due to network issues or bandwidth problems. We ended the experience with just over 700 students and 20 teachers. As graduate students facilitated the OOC, they gained even more time with Minecraft play, either helping students build, helping monitor students or rebuilding and enhancing the Minecraft World when K-12 students were not in it. The experience was planned for two weeks; however, several K-12 classrooms were so excited and “into” the experience they wanted to continue. So for some, the OOC stretched into a four-week experience. Over this time, the higher education students continued to engage in the OOC as well.

Throughout the class, higher education students read, blogged, created the learning unit, completed challenges, and facilitated the OOC; but they didn’t get grades for these activities. Instead, I outlined levels of achievement students could reach with each activity and challenged students to “level up.” Students who completed Minecraft challenges sent a screenshot to me, letting me know what level they believed they achieved. If I agreed, I sent them a badge they could display on their blog. Even for adult learners aged 28 – mid-50s, this worked well. My students didn’t display grade anxiety. The students in K-12 who would be participating in the OOC became the focus of the experience – instead of grades. This was an interesting shift that I haven’t seen before the Gamifi-ED experience, but it occurred in both Gamifi-ED and Givercraft; therefore, I believe this is replicable within the formula for design. Of course the final paper for EDET 693 did need to be graded in a traditional way; however, all students provided strong evidence that they met and exceeded all standards targeted for the class.

OOC Survey Results

According to sixteen K-12 teacher responses at the end of the experience, 100% of the students who participated were “Highly Engaged” (as opposed to Somewhat Engaged, Rarely Engaged or Not Engaged).

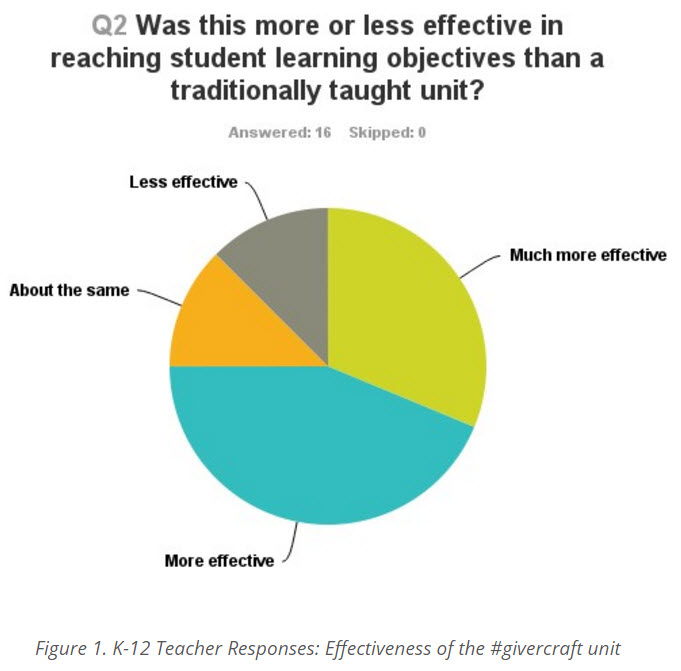

Seventy-four percent of participants believed that the Level Two instructional unit was well-aligned with Common Core standards, while 26% percent believed the unit “might” be well aligned with Common Core standards and none indicated the unit wasn’t aligned with Common Core Standards. In addition, 64% percent of participants believed that the rubric was valid, while 36% percent believed that while students learned something, their learning was not aligned with the rubric, and none believed the rubric was not valid. As outlined in Fig. 1, 75% of respondents found the #givercraft unit More Effective or Much More Effective than a traditionally taught unit. Twelve percent found the unit As Effective, and 12% found the unit Less Effective.

As outlined in Table 1, K-12 teachers who participated in this experience characterized themselves primarily as Somewhat Innovative – willing to take risks with help and support from others – with a smaller population identifying as Very Innovative, and one teacher identifying as Somewhat Traditional.

[table id=5 /]

Table 1. Characterization of Teaching Style: K-12 Teachers

All but one K-12 teacher who responded to the survey indicated that they would participate in this project again, and all K-12 teachers indicated that they would recommend a similar project to others.

Discussion

We found early in the gaming experience that if we provided the K-12 teacher with the administrative password for Minecraft, and if the K-12 teacher was in the game with their students, the students were on-task for the most part. Those who were not on task were quickly dealt with in their physical classroom and didn’t disrupt the rest of the community. On the other hand, if students were in the game without the teacher, we found students were more likely to engage in “griefing” behaviors (a gaming term meaning “giving someone grief” through general harassment) and off-task behaviors. The teachers who supplemented the OOC with in-class discussion also seemed to have classes who were more dedicated to building according to the unit plan. These students demonstrated well the connection between the book and the game.

As in any free and open experience, K-12 teachers who enrolled their students in this experience had differing motives and goals. It became very clear to the graduate students that some K-12 students in the experience either hadn’t read The Giver or were not playing with The Giver as a central focus. They built structures inappropriate to the community (e.g., highly colorful or shaped like swords or stars). They also asked to engage in activities which were not appropriate to behavior in the community – spawning animals for instance or setting off fireworks. Among the facilitators, we explained this behavior through noting that most students play Minecraft at home, without the rules that were in place during our OO and wanted to play Minecraft the way they were accustomed to outside of the classroom. It did become obvious to us, through scores and through use (or lack thereof) of the Wiki, that some teachers weren’t emphasizing the OOC as a literacy experience, and were, instead, using this experience for the purpose of building computer skills, enhancing digital citizenship, or supplementing the book with free play time. This helps to explain the percentage of teachers who believe the unit “might” be aligned with CCSS and the percentage of teachers who believed their students learned; however, they didn’t learn what was represented in the rubric.

Lack of teacher presence in some classrooms might have been attributed to lack of teacher confidence in Minecraft. Suggestions for the next iteration of this experience included:

- More explicit instruction in Minecraft prior to the start,

- Separating writing time from gaming time, instead of lumping the two together, and

- Including more standards. (One teacher shared that he or she was actually chastised by the administration for spending two weeks on four standards in a game – even though the teacher believed these standards were met in an in-depth way. This same teacher is the one who wouldn’t participate in the project again, noting that they got in enough trouble for doing it the first time.)

Research implications

The findings from use of the higher education framework for this experience seem to affirm the effectiveness of some elements of both connectivist and rhizomatic learning. In terms of connectivist practice, the networks that were created during this experience were invaluable to learning within the team. These networks contained, by virtue of their members, a great deal of knowledge. This bears out the principle: “learning is a process of connecting specialized nodes or information sources.” (Siemens, 2005, np) Several networks were created during this experience – within and among graduate student blogs, twitter, youtube, Google and Minecraft – and these represent only the networks used in the formalization of the course. The informal networks created and tapped by individuals were even more intricate and complicated. According to the survey, K-12 teachers found the networks created through Google Groups and Google Text the most helpful during the experience. However, these networks have not endured beyond the MOOC experience. The twitter channel was judged as the 4th favorite communication tool (just ahead of email); and on Twitter, an organic community of participants has emerged and remains under the #givercraft hashtag.

A second principle of connectivism seems to be reflected well in this experience: Capacity to know more is more critical than what is currently known. (Siemens, 2005, np) At the beginning of the experience, there was no knowledge base within the higher education students as a whole – or within myself as a facilitator – which would provide definitive evidence that we would be successful in this endeavor. That is, none of us had planned or conducted a K-12 OOC before, none of us had been responsible for managing a class with Minecraft, and the majority of us hadn’t read The Giver. We all had some individual skills that could transfer to this experience; and while those skills (teaching online, participating in higher education MOOCs, teaching young adult literature, designing online instruction, mentoring other teachers) were well established, the jump to the facilitation of a global K-12 gaming environment was a significant one. However, by focusing on what we could learn, with an ongoing goal of interacting with others to both continue to enrich our own knowledge and enhance theirs, we learned what needed to be known and continued to learn through and beyond the OOC experience. Had we focused only on what one individual knew and was able to do at a static point in the experience, it is unlikely we would have dared to risk this activity. I would posit that even though no one emerged from this experience with a shared expert understanding of any common component of the experience (myself included), each emerged with a basic shared competency in the targeted standards and with individual and unique expert knowledge according to their role in the experience.

Which brings us to a principle of rhizomatic learning which seems to emerge as a theme from this research: within this course, we experienced the community as the curriculum. (Cormier, 2008) Higher education students read from the text, played the game, created their understanding, posted blogs, created youtube videos, posted tweets, read the blogs and watched the videos of others; and then started all over again using their own distinct patterns of learning. They called meetings at nine in the morning or at seven at night with whoever might have been online to discuss whatever might have been on their mind. They filtered, remixed and shared the information of most importance to their role in the experience, and they ultimately applied it to a four-week OOC for over 700 K-12 students.

At the conclusion of the class, my students reflected on the experience and expressed what they believed they had learned.

One student stated,

“Teachers took an incredible risk by signing up to participate in Givercraft, and I felt committed to doing everything I could to earn and keep their trust throughout our project. This project and semester were far from easy; I think being responsive to teachers and being willing to learn and evolve certainly helped us facilitate a meaningful experience. I have learned to plan meticulously but to balance that with flexibility and creativity.”

Another shared,

“We have ignited a spark within the teaching community that has nowhere to go but up in flames. It’s time to burn up the old style of direct instruction and engage students with inspiring projects that encourage them to think, to create, and to enjoy. One word: Intense. It’s time to intensify teaching in our world – and GiverCraft has done just that.”

In conclusion, it might seem from the narrative, that the higher education class was a massive class or an at least a large class. In actuality, the higher education class was composed of six very committed students. There was no room in the class for anyone to become invisible, considering the task that we tackled, and no one did. This semester, a different class will repeat the #givercraft experience, and we will add on a mixed experience combining Lord of the Flies with Maze Runner. As a result of the course in the Fall as well as lessons from Gamifi-ED, this spring I will set some boundaries concerning the time that should be spent in the course. But unlike courses prior to these, my recommendations will emphasize the maximum time students should allow themselves to indulge in the course experience, rather than the minimum time required for a grade. As consuming as this project was, I am rather enjoying the shift in emphasis.

References

Cormier, D. (2011). rhizomatic Learning – Why we teach?. Blog post. Online. Available at http://davecormier. com/edblog/2011/11/05/rhizomatic-learning-why-learn/(accessed 03 January 2015).

Cormier, D. (2008). rhizomatic-education-community-as-curriculum. Blog post. Online. Available at http://davecormier.com/edblog/2008/06/03/rhizomatic-education-community-as-curriculum/(accessed 03 January 2015).

International Society for Technology in Education. (2011). ISTE Standards Coaches. Retrieved from http://www.iste.org/standards/standards-for-coaches on January 3, 2015.

Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: game-based methods and strategies for training and education. John Wiley & Sons.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International journal of instructional technology and distance learning, 2(1), 3-10.

Tapscott, D. (1998). Growing up digital (Vol. 302). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. ASCD.

Endnotes

You can learn more about this project by watching this video, in which we discuss the way that the project formed and the lessons we were taking from it. In addition, all of our webinars with experts are archived on the GamifiedOOC YouTube channel; Vicki’s students’ work is archived and continues at the Gamife-ED Wiki.

This blog post was written by Lee Graham, Ph.D., Associate Professor, University of Alaska Southeast.