My high school students have always struggled with procrastination.

Whether it’s waiting to do their homework until three minutes before the bell rings or waiting to finish a big paper the night (or morning) before it’s due, many of them freely admit: they have a problem.

If I’m honest, they’re not the only ones with a procrastination problem.

I struggle with procrastination, too. In some ways, this has been helpful. Throughout my career, I’ve had many classroom conversations about setting realistic goals, planning ahead, and sticking to those plans.

Interestingly, the term “executive function” has never come up explicitly in these classroom conversations. But with the education world’s recent focus on executive function skills, I’ve realized that they should be a focus in our discussions about procrastination — and beyond.

According to Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child:

Executive function and self-regulation skills are the mental processes that enable us to plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks successfully. Just as an air traffic control system at a busy airport safely manages the arrivals and departures of many aircraft on multiple runways, the brain needs this skill set to filter distractions, prioritize tasks, set and achieve goals, and control impulses.

Considering this definition, it seems intuitive that procrastination and issues with executive function are related. Projects, papers, and assignments often pile up for students because they have trouble resisting distractions, prioritizing what’s important, and controlling impulses.

As I looked into it more, I found that some studies have also identified a link between executive function and procrastination.

Of course, procrastination is not always a result of executive function deficit or dysfunction. Still, the connection has compelled me to consider how to bring more focus to executive function skills in my instruction.

Our students are not born with executive function skills.

Instead, these skills need to be built and developed as children grow.

Amazingly, that potential for development and growth never stops. That means that no matter what age our students are (or even what age we are), there’s always room for expansion.

As a teacher, that makes me feel inspired and optimistic. It reminds me that I am responsible for providing support so students can develop these skills in my classroom.

Recently, I came across The Study Skills Handbook by Stella Cottrell. This book is aimed at undergraduate students, but I found myself wanting to modify some of her resources to build my high school students’ executive function skills.

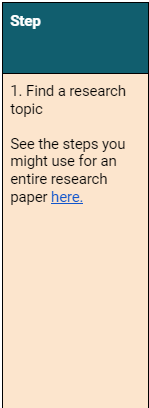

I loved Cottrell’s activity called “planning backward from deadlines,” so I created a version that can be used with adolescents working on extensive activities or projects in any grade level or subject area.

It’s a straightforward remedy for the ever-present problem of procrastination. Even better, it provides many opportunities to strengthen executive function skills.

Click here to access my adapted template→

Here are three things I love about this resource:

1. It provides space to break down projects and activities.

According to Gina DiTullio:

“Long-term assignments can be particularly challenging for students with deficits in executive function. One way to address this issue is by directly teaching students how to map out larger projects and break them down into smaller, more manageable pieces.”

If the project or activity your class is working on will cover the span of a week, month, or even longer, it can be challenging for students to stay organized, motivated, and on task.

The first column on this resource allows you and your students to break down the project into smaller parts to address this issue.

Not only does breaking a task down make the individual parts seem more manageable, but it can also clarify smaller objectives within the work necessary for success.

Breaking larger work down like this can help students organize, prioritize, and better understand the specific procedural knowledge of your subject matter.

There are a lot of different ways that you can use the first column. If you’re using this resource for the first time with students, or if your students are younger, you can fill in the entire first column yourself. I modeled this in the example provided.

To model your thought process, you may consider talking students through how you decided on each step and the order in which you’ve written them.

Once your students have seen this resource a few times, or if you’re working with older students whose executive function skills and subject area knowledge are more developed, you might include students in breaking down the steps necessary to complete a large piece of work.

Later, when students have had practice co-planning with you, they can use this resource to break down student-centered projects and tasks that they themselves construct.

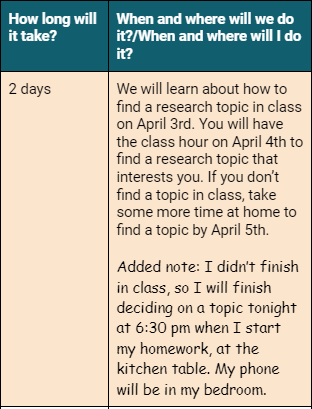

2. It helps students manage time through clarity and specificity.

The second and third columns in this resource are about time and place. The second column asks how long a step will take, and the third asks when and where students will spend that time.

The third column also asks students to identify responsibility for a task: “When and where will we do it?” draws attention to what you will do together as a class, and “When and where will I do it?” draws attention to what students need to do individually.

When students understand how long a step will take and can envision exactly how and where they will spend that time, it can make it easier for them to get started with that task and sustain their effort through its completion.

In the example, you’ll notice that the student specifies that they’ll work at their kitchen table. They also define something else about their workspace: their phone won’t be there. With this clarity, the student is likelier to have a successful homework session.

Like the first column, the second and third columns also invite flexibility. As you begin to use this resource, you may choose to fill the columns in yourself to provide clear guidance for your students. I modeled this in the example.

If you fill these columns in yourself, you can encourage students to make personal notes. I included an example in Comic Sans font of what a student might add to the third column after realizing they’d be responsible for doing some work at home.

As you and your students become more familiar with this resource, you can hand over more responsibility for managing time.

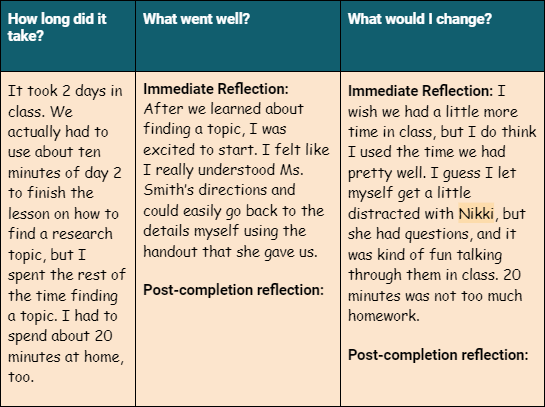

3. It provides many opportunities for reflection.

A vital component of strong executive function skills is the ability to self-regulate. While this skill may seem difficult to teach, an effective way to build these skills is by providing space for reflection throughout a project or activity.

The last three columns of this template allow students to self-monitor and reflect on what did and did not work well after completing work.

Though you might fill out the first three columns for students (as I did in the example), students should definitely fill the last three columns in themselves.

This isn’t to say they should be totally on their own. Especially as you begin working with this resource, it makes sense to give students time and support in class to answer these questions.

For example, as you give students time to answer “How long did it take?” you might review how much time you spent together in class and whether this matched your expectations as the instructor.

Explicitly discussing your own time management can also provide a model for students to follow as they work on the task at hand and as they move on to future assignments.

As you give students time to fill in the last two columns about what went well and what they would change, you can give them examples of topics they might discuss.

For example, students might talk about:

- Their interest level

- How confident they felt about the task

- Gaps in understanding that they realized while working, or

- The amount of engagement and distraction they felt.

You, as the teacher, can also model your thoughts on these topics.

Another option you have for the last two columns is to allow space for students to reflect immediately AND after they’ve completed the entire project.

In terms of executive function skills, both types of these reflections are valuable.

The immediate reflection gives students the ability to self-monitor as they’re working. They can build on the success they’re feeling and course-correct if things are going awry.

The post-completion reflection might elicit different, more nuanced thoughts after students have experienced the entirety of the work process.

Students can then reflect on what did and did not go well in the project as a whole and consider how to apply their findings to their work in the future.

Ultimately, the greatest thing about this resource is that it builds skills fundamental to almost every aspect of students’ lives.

And, yes, it doesn’t hurt that it can encourage them to conquer their procrastination habits and turn in higher-quality work, too!

If you are interested in learning more about strengthening executive function skills in your classroom, here are some other resources you may want to check out:

- What Is executive function? And how does it relate to child development? (Infographic from Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child)

- Helping students develop executive function skills (Edutopia article)

- Enhancing and practicing executive function skills with children from infancy to adolescence (Activities guide from Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child)