10 essential instructional literacy practices serve as a “minimum standard of care” to — quite literally — save the lives of our students

Michigan is in the midst of a literacy crisis. For years, educators in our state have been aware of this reality; however, recent statistics have painted a picture so grim that we can no longer afford to ignore it.

Let’s take a look at our 2015 M-STEP data, for example. From this data, it became clear that only about 50 percent of our state’s third graders are proficient readers. Other concerning statistics — from the Early Literacy Task Force’s Executive Summary — include:

The fact that Michigan ranks…

- 41st among U.S. states in fourth-grade reading scores, based on the 2015 National Assessment of Education Progress

- 45th among U.S. states in fourth-grade reading scores for students who are economically disadvantaged

- 48th among U.S. states for students who are economically advantaged

Given these statistics, it’s easy to see that we have a literacy crisis on our hands. But what perhaps isn’t as readily obvious is how this literacy crisis constitutes a public health crisis.

Literacy Crisis = Public Health Crisis

This perspective belongs to Dr. Nell Duke — a professor of Literacy, Language and Culture at the University of Michigan — who argued eloquently for this position at her keynote presentation given at the 2018 Michigan Association of School Administrator’s (MASA) Midwinter Conference.

Her argument goes something like this:

We know that students who fall below literacy standards in third grade are likely to continue struggling throughout the rest of their education.

Why is that?

Ultimately, it boils down to the difference between learning to read and reading to learn.

Learning to read

Students receive explicit instruction in how to readReading to learn

Students are expected to use reading as a means to acquire new information

At a certain point in every student’s educational career, they receive less and less explicit instruction in how to read and are instead asked to use reading as a means to gather content-specific information.

“When we comprehend, we gain new information that changes our knowledge, which is then available for later comprehension. So, in that positive, virtuous cycle, knowledge begets comprehension, which begets knowledge, and so on. In a very real sense, we literally read and learn our way into greater knowledge about the world.”

— Nell K. Duke, P. David Pearson, Stephanie L. Strachan, and Alison K. Billman

The problem with this model soon becomes apparent.

If a student does not catch up to their peers in literacy standards by the end of third grade, they are at a severe disadvantage when it comes to acquiring new knowledge via reading for the rest of their education and, likely, for the rest of their lives.

The worst part is:

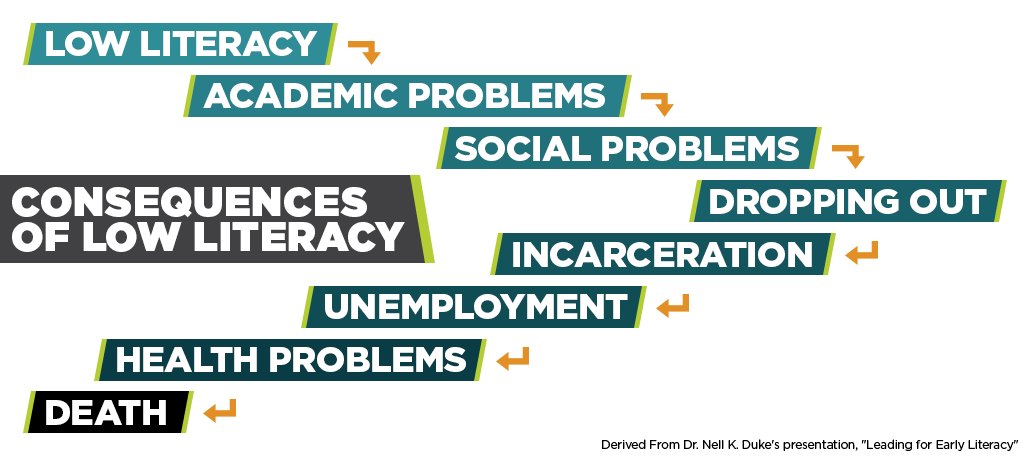

This disadvantage extends beyond their time in public education. Derived from a slide in Dr. Nell Duke’s presentation, “Leading for Early Literacy,” the graphic below illustrates how low literacy can lead to a host of other social, economic and even medical consequences, including incarceration, unemployment, health problems and even premature death.

The Victims of This Cycle

You can see this reality reflected in statistics on the quality of life for those with low literacy rates. According to a 2015 report published by the Center for Public Education, as literacy rates go up, so do wages.

Adults with poor literacy rates, they claim, are more likely to have poor health, less likely to vote and less likely to break the cycle by actively performing reading activities with their children.

These trends disproportionately affect poor students and students of color.

While it’s an urban myth that prisons use third-grade reading levels as a predictor for future inmate numbers, it’s not a myth that students who cannot read at grade-level by third grade are four times less likely to graduate high school, according to a study by sociologist Donald Hernandez. Further studies demonstrate the link between dropping out of high school and incarceration rates.

Such statistics reveal the beating heart of the early literacy movement. It’s not just about making sure our children can read literature or put commas in the right places. It’s about making sure they have the tools they need to learn and, therefore, the tools they need to live a healthy and successful life.

That’s why it’s so frightening that 50 percent of Michigan third graders do not meet literacy standards.

What You Can Do to Help

Dr. Nell Duke is perfectly clear in stating, “We must disturb the comfortable in Michigan literacy.”

“We must disturb the comfortable in Michigan literacy.”

— Dr. Nell Duke

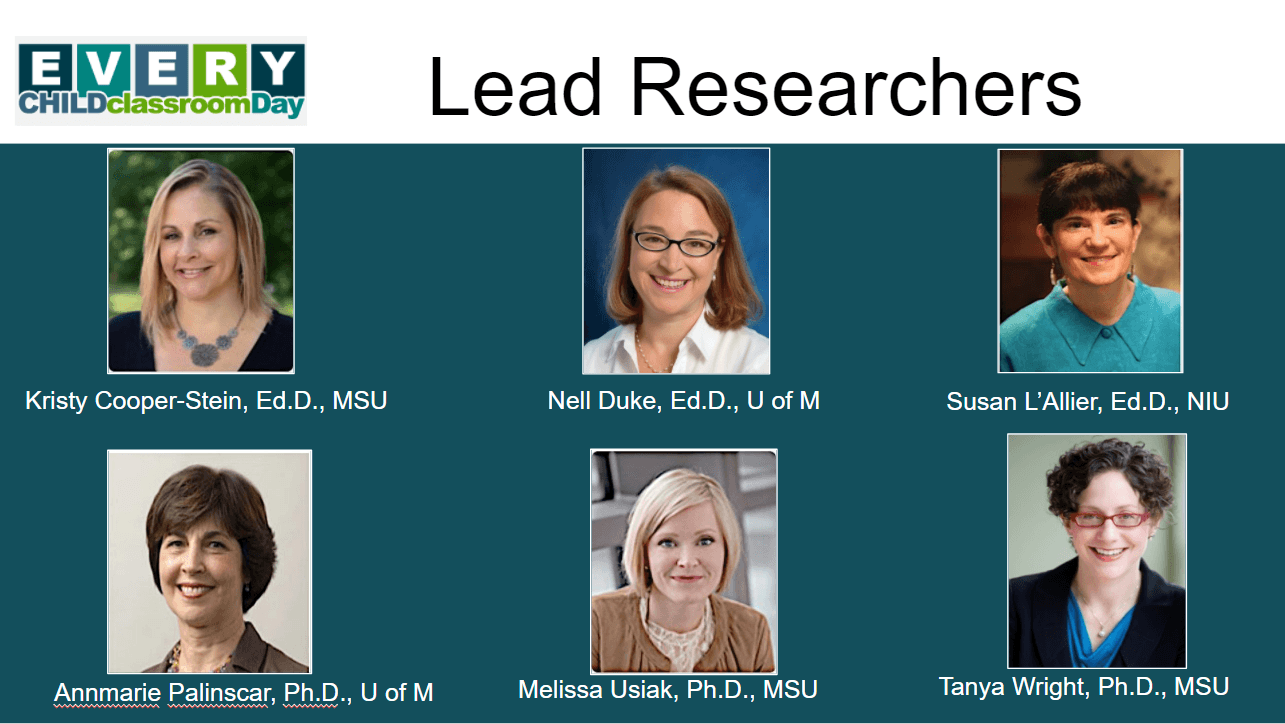

Ultimately, to push toward a paradigm shift in literacy instruction, the Early Literacy Task Force was created by Michigan’s General Education Leadership Network, a Michigan Association of Intermediate School Administrators (MAISA) collaborative. The lead researchers on this task force include Dr. Kristy Cooper-Stein, Dr. Nell Duke, Dr. Susan L’Allier, Dr. Annmarie Palinscar, Dr. Melissa Usiak and Dr. Tanya Wright.

In creating this task force, leaders from many of our state’s educational organizations came together to find common ground, to agree upon what constitutes evidence-based essential instructional practices for Pre-K-third-grade students and to determine best paths for action moving forward.

And they’ve found it. Common ground, that is.

Together, they’ve agreed upon 10 essential practices that serve as a “minimum standard of care” when it comes to fostering literate students and literate citizens.

The task force has created several short guides overviewing ways to apply these 10 practices in various grade-levels and contexts, including:

- Essential Instructional Practices in Early Literacy, Prekindergarten

- Essential Instructional Practices in Early Literacy, Grades K to 3

- Essential Instructional Practices in Early Literacy, Grades 4 to 5

- Essential School-Wide and Center-Wide Practices in Literacy

- Essential Coaching Practices for Elementary Literacy

To be clear, these 10 practices represent a minimum standard of care necessary for students to gain age-appropriate literacy skills.

Meaning, at a bare minimum, each of these 10 things should be done in every classroom for every student every day.

“We’re setting the floor for what should be expected in Pre-K- to third-grade everyday. On top of these, you typically need to layer more interventions and supports for a robust literacy program.”

— Ken Dirkin

“We’re setting the floor for what should be expected in Pre-K- to third-grade everyday,” says Ken Dirkin, director of online professional learning at Michigan Virtual. “On top of these practices, you typically need to layer more interventions and supports for a robust literacy program.”

Changing the Paradigm in Early Education

It’s true that these expectations place a lot of stress and responsibility on early year educators. The goal, however, is to change the paradigm of how primary education is taught, so active literacy instruction becomes a fluid and natural part of the work of the classroom.

Some — like Nancy Carlsson-Paige, co-founder of Defend the Early Years advocacy group — argue that our rigorous focus on literacy causes young children unnecessary stress and deprives them of highly-valuable time for play.

Most literacy experts say this is a false dilemma.

“I’ve seen so many kids that are delighted reading to dolls and then going to a story chart, taking the pointer, and tracking print, and they’re finding it to be the most fun in the world. It depends on the conditions.”

— Dr. Kathleen Roskos

“You can have a classroom that’s very unplayful, and kids are still learning very little literacy in there, or you can have a playful one, and they learn a lot of literacy,” says Kathleen Roskos, professor of education at John Carroll University. “I’ve seen so many kids that are delighted reading to dolls and then going to a story chart, taking the pointer, and tracking print, and they’re finding it to be the most fun in the world. It depends on the conditions.”

“I don’t think anyone is wanting to get play out of the kindergarten classroom.”

— Dr. Nell Duke

Dr. Nell Duke echoes this point, saying, “Kindergartners can and should use play to reach the standards. The dichotomizing of play with academic development is a problem. I don’t think anyone is wanting to get play out of the kindergarten classroom.”

You can read more about this debate here, but the moral of the story is:

It’s time for sea change in the intentionality of teaching literacy skills, but that doesn’t mean we can’t allow children to enjoy the process of learning along the way.

We must turn the tide for Michigan’s children — their lives depend on it.

Further Resources

- To read more about early literacy myths vs. facts, check out this brief by Student Achievement Partners.

- If you’re interested in learning more about the 10 essential instructional practices in early literacy, visit the Literacy Essentials website.

- As part of the Early Literacy Task Force, Michigan Virtual has created a series of free online courses on essential instructional practices in early literacy, created in partnership with the Michigan Department of Education and MAISA. Enroll in early literacy courses here.