Whether your school is starting the year with in-person instruction, using a hybrid model, or teaching completely online, you will need to be flexible. You may even be asked to shift back and forth between different models of instruction throughout the school year.

Regardless of what learning environment you and your students find yourselves in, this is a challenging time for both teachers and students alike. So it is crucial that you have processes in place to monitor your students’ needs—both academic and non-academic.

In fact, in a learning environment that is designed to be student-centered, continuously monitoring student needs may not only be more easily accomplished, but can also lead to opportunities for learner agency by also encouraging students to learn more about themselves and how they learn best.

As we wrap up our Student-Centered Learning blog series, this is the third post of four in our mini-series, Engage and Empower Learners: How Student-Centered Learning Supports Learning Continuity. In this mini-series, we discuss how adopting student-centered learning principles can actually help school leaders and teachers facilitate the transition to this “new normal” of teaching and learning while still nurturing student growth.

In this post, we will be revisiting a core tenet of student-centered learning: continuous monitoring of student needs. We will explore this concept in more depth to understand why implementing student-centered principles into the learning environment can improve student engagement and make teaching and learning, no matter what environment you and your students find yourselves in, more student-focused.

Continuous monitoring of student needs: Going beyond data

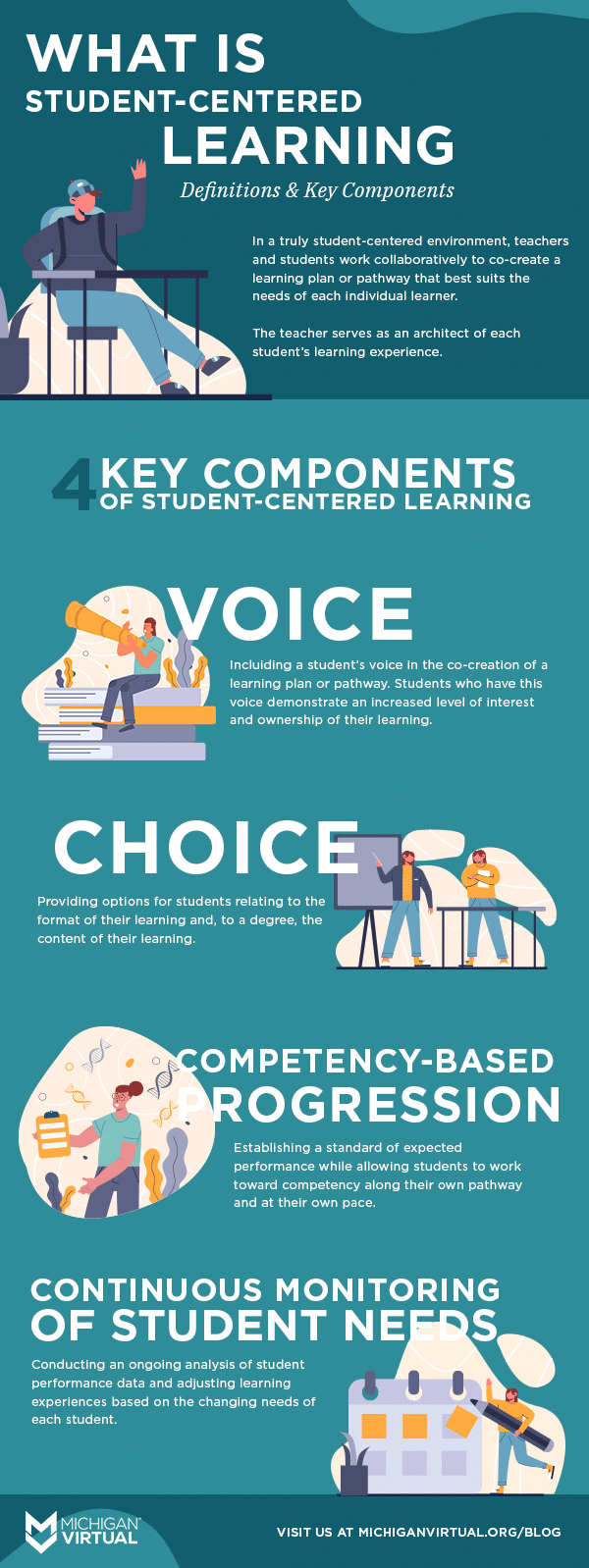

As we discussed in the first post of our student-centered learning blog series, one of the core characteristics of a student-centered learning environment is the continuous monitoring of student needs through the ongoing analysis of student data.

Continuously monitoring student needs provides an opportunity for teachers to adjust or “re-architect” student learning experiences based on the changing needs of each student.

However, in a truly student-centered learning environment, it really goes beyond just data. Teachers and administrators should look at the whole child, considering both their academic and non-academic needs.

Non-academic student needs

In a student-centered learning environment, putting students at the center means really getting to know them beyond the academics—understanding their interests, their passions, and what truly matters to them.

Understanding the non-academic needs of the student can help teachers connect the academic curricular pieces together in ways that work best for that individual learner. For example, if you find out a student has a passion for cars, you may suggest they take some career and technical education courses. Or if a student is really interested in science, you can help them gear their curriculum to be more science intensive.

Knowledge of students’ non-academic needs and interests can help teachers and school leaders make more meaningful decisions for individual students, especially when there is a collaborative process with students in place to facilitate these discussions.

How can we effectively monitor students’ non-academic needs?

Some schools monitor students’ non-academic needs by building an advisory period into student schedules on a regular basis. During the advisory period, students meet with an advisor or academic coach who serves as an advocate for each student in their group.

The academic coach or advisor gets to know the students on both an academic and a personal level. It is their responsibility to see if students are having any general issues and to make sure that each student has what they need to succeed.

Some schools use learner profiles as a way to monitor students’ non-academic needs. In their learner profile, students can share their strengths, challenges, aspirations, interests, and talents.

Coupling learner profile data with student achievement data can help teachers, advisors, and school administrators get to know individual students and can help to guide students in an educational direction based on their interests.

However, a caveat to consider is that while advisory periods, academic coaches, and learner profiles are always implemented with the best of intentions, they shouldn’t be something that is simply layered on. To be effective, they have to be viewed as a central piece of the school’s education process. Otherwise, they may be pushed to the side when competing priorities arise.

Placing importance on considering the non-academic and academic needs of individual students can also help students learn more about themselves and how they learn best.

Academic student needs

In a student-centered learning environment, it is crucial to monitor the academic needs of students in order to make decisions that appropriately shape their learning pathways. Monitoring students’ academic needs can help determine where students are excelling and where they have gaps in their learning.

One source for identifying students’ academic needs is their student-achievement data. While state testing data can help to shape overarching district decisions (e.g., How is the district’s overall math achievement?), that is only one piece of a student’s academic performance puzzle. It is the formative and summative assessments that are the real data.

Frequent formative and summative assessments tell a much bigger and more meaningful story of student learning, one that more accurately describes the academic needs of individual students. However, keep in mind that if the assessment isn’t designed well, you won’t get the data or the answers that you are looking for.

How can we effectively monitor students’ academic needs?

Technology can help streamline the process of gathering data and tracking student academic performance for use by both teachers and students.

Student information systems, such as PowerSchool or Skyward, give teachers an easy way to track student performance over time and can help in identifying students’ academic needs. A learning management system (LMS), such as Brightspace or Canvas, provides teachers a central space for digital assessment and grading tools and offers ways to streamline the process of tracking grades. An LMS also provides students with a central space to locate learning materials and track their own progress and grades.

Most importantly, technology makes it feasible for teachers to track individual student data and monitor individual student academic needs.

When we can effectively monitor students’ individual academic needs, we can also teach students to monitor their own needs. By tracking their own academic progress, students are encouraged to take ownership of their learning, which helps them to develop the skills needed for learner agency.

In their microcredential on student progress monitoring, Digital Promise explains that learner agency has two main components:

- Knowledge of oneself as a learner

- The learner’s ability to articulate, create, or ask for the conditions necessary to meet one’s learning needs

While it is a teacher’s responsibility to know how students are doing overall, students themselves rarely know.

Monitoring their own academic progress is an important life skill for students. It fosters metacognition (awareness of one’s own thought processes), which has been associated with higher levels of achievement.

However, there are a few caveats to consider. While students should have opportunities to track their own progress, we can’t assume that students know how to do this themselves. Monitoring student data should be a collaborative process with both students and teachers looking at the same data and discussing it together.

Monitoring and setting their own goals and progress made towards those goals can help students own their learning and become more personally invested in the process. As Dr. Sarah Pazur, FlexTech’s Director of School Leadership, shared:

“Student-centered learning mirrors what happens in life and the workplace; you have to set goals, take action, manage your time, reflect and revise, and have a belief in yourself that you can improve.”

Student-centered learning can help students develop both academic and non-academic skills transferable beyond the classroom.

Continuous monitoring of student needs and learning continuity

It is important to remember that when we talk about continuously monitoring student needs, we must mesh both academic and non-academic monitoring to get the whole picture of each learner.

Understanding a student’s non-academic needs can oftentimes help us to make better informed decisions about their academic needs, increasing their chances of engagement in the learning process and academic success.

Learning management systems help to capture academic data and put it in formats that are more useful to both students and teachers. And the availability of technology is making monitoring student needs—and student-centered learning in general—more possible, especially when students are 1:1 (each student has an appropriate learning device).

The reality is that some of this monitoring of student needs is sometimes a bit more straightforward in a face-to-face setting. In a face-to-face classroom, teachers can more easily monitor understanding and learning because they can see it.

When teachers who have little or no prior online teaching experience are asked to teach online, monitoring student needs is something that may be a struggle without the visual cues they are used to seeing from students.

However, when students have voice and choice in terms of demonstrating their understanding—when they can show their learning in a way that makes sense to them—teachers should be able to more easily monitor students’ needs and assess their learning, no matter if they are teaching remotely or face-to-face.

Final thoughts

In talking to school leaders and teachers, those schools that had an easier time making the shift to remote learning last spring did so because they were able to leverage the processes and the technology they already had in place.

Schools that already had elements of student-centered learning—whose students were used to having voice and choice, used to progressing in a competency-based learning environment, and used to monitoring their own learning—made that shift much more easily. As Dr. Pazur explained in a previous post,

“Schools that have created the conditions for student agency are going to have an easier time with rapid or extended closures because students aren’t waiting on the adults or the system to tell them what to do. They [students] are inspired by the work they’re doing because they had a voice in shaping and designing it—they created it and it doesn’t live in the school building. When the student drives the learning, the arbitrary structures like class periods and teacher-driven lessons in the form of worksheets or rote learning tasks become obsolete.”

Isn’t that the goal? Inspired students. Students who see that learning doesn’t live only inside the classroom. Students who see connections to real-world situations. Students who have opportunities to work at their own pace and to show what they know in a way that makes sense to them.

Students who understand how they learn best and can monitor their own learning.

Student-centered learning is about more than just putting students at the center of education. It is about giving each student the opportunity for success. It is about designing learning to be flexible and adaptable for each learner, not just the average student.

It is about understanding the whole child—what they need both academically and non-academically—and giving students the skills they need for success within and beyond the classroom.

Student-Centered Learning Blog Series

In our Student-Centered Learning blog series, we lead a discussion each month about student-centered learning: what it is, how it can help students and schools, and how to make it a reality. Our hope with this series is to provide practical insights to school leaders, teachers, and parents on how to make education more meaningful to students. Stay up to date on future blogs in this series by signing up for email notifications!

About the Authors

Christa Green

Christa received her master’s in Curriculum and Instruction from Kent State University, as well as a bachelor’s degree in Business Administration. She taught middle school language arts and social studies for seven years before coming to work for Michigan Virtual in 2018. As a research specialist with the Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute, Christa enjoys using her passion for education, curriculum, research, and writing to share and shape best practices in online and blended learning with other educators within and beyond Michigan.

Christopher Harrington

Dr. Christopher Harrington has served public education as a teacher, an administrator, a researcher, and a consultant for more than 25 years and has experience assisting dozens of school districts across the nation in the design and implementation of blended, online, and personalized learning programs. He has worked on local, regional, and national committees with the Aurora Institute (formerly iNACOL) and various other education-based organizations aimed at transforming education through the use of technology.