Introduction

In the State of Michigan, schools are required to provide students taking online courses with a mentor—an employee of the school district who provides student support (Michigan Department of Education, 2022). This support may consist of helping students with day-to-day aspects of their course(s) such as course pacing, proctoring exams, providing technical assistance, and helping students communicate with their instructors. While mentors are not required to be course content experts, they are an integral part of students’ experience with online learning. Before a course even begins, mentors may assess students’ readiness for online learning, and place them in courses that best match their needs (Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute, n.d.). Mentors are also likely to support students in virtual learning more broadly by helping students learn how to learn online (Borup & Stimson, 2019; Michigan Department of Education, 2022; Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute, n.d.).

Mentors may provide students with some sort of structure for working through their online courses (e.g., lab period, check-ins), a practice that is highly effective and translates to greater pass rates (Borup & Stimson, 2019). Setting clear expectations at the beginning of the term about course logins, communication, and how to use in-person meeting times effectively can be helpful in this regard (Herta, 2022). Mentors may also encourage and motivate students to stay on track and engage with course material in meaningful ways (Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute, 2020). Forming strong relationships with students is critical as it enables mentors to offer more personalized support, guidance, and encouragement (Borup & Stimson, 2019; Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute, 2020). Indeed, forming relationships with students, and providing encouragement are two of the most important mentorship qualities (DeBruler & Green, 2020).

Results from a survey of students who were supplementing their brick-and-mortar classes with classes through Michigan Virtual indicated that relative to teachers, on-site mentors were the most common source of student support (Borup, Chambers & Stimson, 2018). As such, mentors can be a consistent resource (or “go-to” person) for students. They can be especially helpful when teachers are busy with other students, or when students (and/or caregivers) are unfamiliar with the expectations and requirements of online learning (Michigan Virtual, 2020). Importantly, having mentors can improve virtual course pass rates (Roblyer et al., 2008; Lynch, 2019). While a growing body of research clearly indicates the benefits of high-quality mentoring, there is considerable variation across the state in regard to how mentors carry out their assigned responsibilities, the support they have access to, and their workload.

The Current Study

This study combined available data from the Michigan Virtual Student Learning Portal (SLP) with survey data collected from Michigan Virtual Mentors in order to better understand the contexts in which mentors work (including usage of BrightSpace and SLP), alongside their use and perceptions of certain student support practices. In light of this purpose, several research questions emerged:

- What is the typical student load for mentors? Does student load vary by mentors’ experience or percent of students qualifying for Free-Reduced Price Lunch?

- How are mentors using the Michigan Virtual SLP? How frequently do mentors use specific tools within the SLP and BrightSpace?

- What do mentors consider to be the most effective practices for supporting online students?

- How often and in what ways are mentors communicating with students and instructors?

A better understanding of how mentors navigate their roles will allow Michigan Virtual to develop more effective mentor support. Better understanding mentors’ perceptions and usage of specific strategies can inform future research on effective practices, provide insight into the support typically needed by online learners, and allow for the recommendation of strategies to support online students.

Methods

Survey Data

All mentors who were assigned students enrolled in Michigan Virtual courses during the Spring 2023 semester were sent a year-end survey via Qualtrics Research Suite. The survey consisted of 32 multiple-choice and open-ended questions organized into five sections. The first section assessed mentors’ satisfaction with Michigan Virtual and their use of the SLP, the second section examined the ways in which mentors monitored student progress, the third section assessed perceptions of mentorship practices, the fourth investigated communication, and the last section gauged interest in mentor-specific professional development. Questions pertaining to communication, perception of SLP, use of tools within the SLP, and perceptions of mentorship strategies/practices were analyzed in order to answer the relevant research questions outlined above.

Student Learning Portal (SLP) and BrightSpace Data

Because the goal of the current study was to better understand how mentors navigate their roles as it relates to student support, data was pulled from the two main interfaces used by mentors. Frequent communication and ensuring that students are logging into their courses daily are both considered to be “best practices” for mentorship according to Michigan Virtual (“Best Practices of Mentoring Online Students,” n.d.), so communication and login data were the focus of analyses. It is also reasonable to hypothesize that the number of students assigned to a mentor may impact their ability to monitor each student, thus, looking at the number of students assigned to a mentor was critical. It is important to note that this data only provides a “snapshot” of mentor-student interactions because mentors may communicate with students outside of these interfaces (e.g., email), and thus this may not provide a fully generalizable picture of what mentor-student communication looks like. This dataset also provided information about the economic categories of mentors’ school building and districts—this information was used to examine student load based on such characteristics. Mentors who did not have economic information associated with their buildings were excluded (N = 207, see Appendix A).

The SLP is a system where students are registered for and enrolled in courses. The SLP is also used to monitor student progress as it allows for mentors to track grades, attendance, and reports, as well as communicate with students. Brightspace is a learning management system (LMS) that houses students’ course content (e.g., materials, assignments, tests; “Best Practices of Mentoring Online Students,” n.d.). Mentors receive a copy of all communication between online teachers and students who are assigned to them (“Affiliation Presentation: Student Learning Portal,” n.d.). The SLP allows mentors to view the entire gradebook for any student, but BrightSpace has a variety of features that they can use to take a deeper dive. For example, the progress summary function enables mentors to see students’ performance on specific assignments, course access, and points earned out of total course points (“Mentor Guide to BrightSpace,” n.d.).

Some individuals assigned the role of “mentor” may not actually serve in a student support role, but serve as administrators or school staff responsible for enrolling students in online courses. As a result, these individuals may be assigned particularly large numbers of students. Therefore, to ensure the accuracy of the data, mentors with student loads exceeding 200 were removed from both data sets (N = 2 from survey dataset; N = 4 from SLP dataset).

Results

What is the Typical Student Load for Mentors?

According to the year-end survey, mentors had approximately 30 students on average (M = 29.8, SD = 33.0) in the Spring of 2023. The number of students assigned to mentors, however, ranged from 2 to 150. Half of the mentors reported being assigned less than 20 students, and half of the mentors reported being assigned more than 20 students. The histogram below shows that most mentors had between 0-15 students, with very few supporting 94 or more students.

Figure 1. Histogram Displaying Mentors’ Self-Reported Student Leads

According to data from the SLP, mentors had approximately 15 students on average in the Spring of 2023 (M = 14.7, SD = 23.6), which is half of what was reported in survey data. The range of students assigned to mentors was similar (1 to 184) to what was reported in the survey data. Similarly, the median1 of the SLP data indicated that half of the mentors had less than 5 students in the Spring of 2023, while half of them had more than 5 students. Discrepancies between survey and SLP data may stem from mentors’ self-selection into the survey, making it potentially more likely that mentors with certain characteristics were under or over-represented in survey data. On the other hand, mentors may have additional students taking online classes through a provider other than Michigan Virtual, and thus those students are not represented in the SLP system.

1 When data is arranged in order, the median represents the middle value that separates the higher and lower halves. It is often considered a reliable indicator of the typical value in a data set because it is less impacted than the average by extreme values.

Does Student Load Vary by Mentors’ Experience or the School’s Economic Category?

Mentors who have been in their role for five or more years had the highest number of students assigned to them on average (M = 38.0, SD = 33.4). Mentors with four to five years of experience had the fewest number assigned to them on average (M = 20.9, SD = 27.2). Given the variation in the number of students assigned to mentors, which may skew the average, the median number of students assigned to mentors based on experience was examined. Half of the mentors with five or more years of experience had fewer than 30 students while half had more than 30. Mentors in their first year had the lowest median number of students with half having fewer than nine students and half having more than nine students. Therefore, mentors with five or more years of experience seem to consistently have higher student loads.

Figure 2. Mentors Average and Median Self-Reported Student Load by Experience

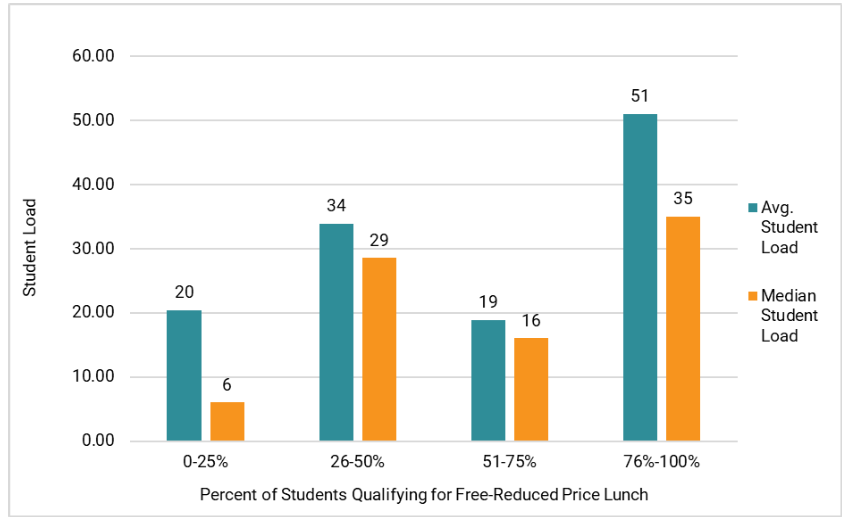

Mentors working in schools where 75-100% of students qualified for Free-Reduced Price Lunch (FRPL) had the highest number of students assigned to them on average (M = 51.0, SD = 47.2). Half of the mentors working in these schools had fewer than 35 students, while half had more than 35. While the average student load for mentors working in schools where 0-25% of students qualified for FRPL was approximately 20 (M = 20.4, SD = 33.7), the median was substantially lower—half of these mentors had fewer than 6 students while half had more than 6. This means that mentors working in schools where 75-100% of students qualified for FRPL tend to have a significantly higher student load compared to those in schools with lower percentages.

Figure 3. Mentors Average and Median Self-Reported Student Load by FRPL

According to SLP data that broke down mentors’ student loads by FRPL, mentors working in buildings (M = 23.3, Median = 6.5) and districts (M = 19.0, Median = 6) where >75% of students qualified for FRPL had the highest average and median student loads, aligning with what was observed in the survey data. At the district level, the median student load was more evenly distributed with mentors working in districts where <=25% of students qualified for FRPL and where >75% of students qualified for FRPL both having a median student load of six. Thus, the building and district-level data generally followed the same pattern as survey data in such that mentors working in schools where >75% of students qualified for FRPL have higher student loads on average. The median number of students was more consistent across FRPL status at the building and district-level compared to what was reported by individual mentors.

How are Mentors Using the Michigan Virtual SLP? How Frequently Do Mentors Use Specific Tools Within the SLP and BrightSpace?

Mentors are part of a four-pronged team to help students succeed in their online learning endeavors. Working alongside students, parents, and instructors, mentor responsibilities may range from helping students get started in their courses to monitoring their progress throughout the term. According to SLP data, mentors logged into BrightSpace an average of 56 days (M = 56.2, SD = 101.6), with half of the mentors logging in fewer than nine days and half logging in more than nine days. Logins to the SLP were more frequent, with mentors logging in an average of 142 days (M = 142.9, SD = 157.9). There was considerable variability with logins ranging from once to 186 times. Half of the mentors logged in fewer than 84 times, and half logged in more than 84 times. So overall, mentors seemed to use the SLP more frequently relative to BrightSpace, but there was still considerable variation in the frequency of logins.

Mentors were surveyed about their use of various student monitoring tools, which they reported using at different frequencies. They reported accessing the enrollment (n = 9, 39%) and report tabs (n = 13, 57%) less than weekly, but the student tab was typically accessed one to two times a week (n = 14, 41%). Mentors reported accessing the Gradebook (n = 21, 40%) and Mentor Report (n = 11, 34%) one to two times a week. While fewer mentors reported using the BrightSpace Observer, they used it fairly consistently, with six mentors (38%) reporting using it three to four times a week and five mentors reporting using it daily (31%). The Dashboard was used less consistently; four used it less than weekly (29%), and four mentors reported using it one to two times a week (29%). Use of any other tool was relatively infrequent as only two mentors reported using some other tool less than weekly (67%). Most mentors said that the SLP was ‘somewhat easy’ to use (n = 33).

| Frequency of Use | Less than weekly | 1-2 times a week | 3-4 times a week | Daily |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Report Tab | 57% | 30% | 4% | 9% |

| Mentor Report Tab | 28% | 34% | 19% | 19% |

| Dashboard | 29% | 29% | 21% | 21% |

| Enrollment Tab | 39% | 17% | 22% | 22% |

| Gradebook | 19% | 40% | 17% | 23% |

| Student Tab | 24% | 41% | 9% | 26% |

| BrightSpace Observer | 6% | 25% | 38% | 31% |

| Other | 67% | 0% | 0% | 33% |

What do Mentors Consider to be the Most Effective Practices for Supporting Online Students?

Mentors use a wide variety of strategies to help students succeed. As part of the survey, mentors were given a list of mentoring strategies based on past research on mentoring and asked to choose the three strategies they believed were the most effective. Mentors indicated that they believed ‘building relationships with students’ (n = 34, 18.9%), ‘monitoring student progress in their online course(s)’ (n = 32, 17.8%), and ‘motivating students to fully engage with course content’ (n = 18, 10.0%) were the most effective strategies.

The strategies that mentors reported as being most effective align with two out of the three broad mentor responsibilities outlined by Borup (2019): nurturing the student, and monitoring and motivating the student. Nurturing the student encompasses many facets, one of which specifically focuses on building relationships. Other facets of this broad category such as advising students and orienting them to online courses/learning were less frequently reported by mentors. Monitoring student progress and motivating students to engage with course content beyond just a surface-level exploration is encapsulated within Borup’s second category, monitoring and motivating the student.

Previous research reported that mentors frequently help students with time management; however, only 6.67% of mentors in our survey noted ‘assisting students with time management’ as one of their top three effective strategies (Freidhoff et al., 2015; Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute, 2020). This could mean that while mentors spend time helping students with time management, they don’t see it as being as or more effective than other strategies. Alternatively, it could be that time management skills vary depending on student characteristics and experience with online learning.

| Mentoring Strategy | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Building relationships with students | 34 (18.9) |

| Monitoring student progress in their online course | 32 (17.8) |

| Motivating students to fully engage with course content | 18 (10.0) |

| Communicating student course progress to the student | 16 (8.9) |

| Assisting students with time management | 12 (6.7) |

| Ensuring students are on task | 11 (6.1) |

| Monitoring student grades | 10 (5.6) |

| Providing the student with structure | 10 (5.6) |

| Facilitating student communication with instructors | 7 (3.9) |

| Helping students access their courses and become familiar with their courses on the first day | 6 (3.3) |

| Providing content instruction/assistance | 5 (2.8) |

| Advising students on online course selection and/or enrollment | 4 (2.2) |

| Orienting students to online learning | 4 (2.2) |

| Having tutoring and other learning resources | 3 (1.7) |

| Organizing physical learning spaces | 3 (1.7) |

| Providing technological assistance to students | 3 (1.7) |

| Communicating student course progress to the instructor | 2 (1.1) |

How Often and in What Ways Are Mentors Communicating with Teachers and Students?

Regular student check-ins are an effective way to ensure students stay on track with course expectations and address any concerns early. Most mentors reported interacting with students either daily (n = 23, 38.0%) or one to two times per week (n = 22, 33.0%).

| Communication Frequency | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Daily | 23 (38.0) |

| 1-2 times a week | 20 (33.0) |

| 3-4 times a week | 10 (17.0) |

| Less than weekly | 7 (12.0) |

Mentors’ main method of student interaction was through email (n = 49, 24.62%) followed by in-person meetings (n = 42, 21.1%). SLP data corroborated that email was the most common communication method used by mentors (n = 8677, 86.0%). Email is likely a convenient way for mentors to check in with students about their progress and assignments, answer specific questions, or help them ‘troubleshoot’ technical issues. Because online learning may pose certain challenges for students, such as pacing and time management, meeting with students weekly is recommended as it allows mentors to assess student progress and build student relationships (Lynch, 2019).

| Mentor Reported Interaction Format | N (%) |

|---|---|

| 49 (24.6) | |

| In-person meetings | 42 (21.1) |

| Classroom | 34 (17.1) |

| Scheduled student work time (e.g. labs) | 18 (9.1) |

| Office hours | 11 (5.5) |

| Phone calls | 8 (4.0) |

| Text message | 6 (3.0) |

| LMS | 5 (2.5) |

| Video conferencing (e.g. Zoom) | 4 (2.0) |

Given that mentors are part of a multi-pronged team, they likely communicate with the course instructor about students’ needs and progress (Bruno, 2019; Lynch, 2019). In fact, Debbie Lynch, former Outreach Coordinator for Mentors at Michigan Virtual, writes, “It is imperative that mentors communicate on a consistent basis with online instructors” (Lynch, 2019). Most mentors indicated they communicated with instructors less than weekly (n = 45, 76.3%). While mentors communicated with instructors less frequently than they did their students, they indicated that the communications they did have were ‘very effective’ (n = 30, 51.7%).

Borup (2018) also cites ‘encouraging communication between the student, parent, and online instructor’ as the third broad category of mentor responsibilities (as cited in Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute, 2020). Only two mentors (1.1%) reported ‘communicating student course progress to the instructor’ as one of the top three most effective strategies, which aligns with the overall low levels of communication with instructors. While mentors were consistent in their communications with students, there was less consistency in communication with instructors. This may reflect students’ level of comfort in terms of communicating with their instructors or mentors’ prioritization of other responsibilities.

Conclusion

Student Load Considerations

Overall, there is considerable variation among mentors’ student load based on the length of time spent as a mentor and their school’s FRPL. On average, mentors working in buildings and districts where >75% of students qualify for FRPL seem to have a greater number of students assigned to them compared to other buildings and districts. Mentors who have been serving in their role for 5+ years had the highest number of students assigned to them, on average. Even mentors with significant experience should be provided with relevant professional learning opportunities so they can connect with other mentors and keep up with online learning best practices. On average, first-year mentors had approximately 20 students assigned to them, a number similar to mentors in their 4th and 5th years. Newer mentors should receive support such as professional learning and opportunities to connect to other mentors to help them fully understand the scope and responsibilities of their roles as well as how to effectively support students in their online courses. Additionally, building and district administrators should be mindful of mentors’ current student loads, other professional responsibilities, and goals when considering the allocation of mentees so that mentors can fully engage with their assigned students to help them succeed in their online courses.

Leveraging LMS Tools for Student Support

In terms of tools that enable mentors to monitor students’ online learning, the gradebook had the highest number of daily users (n = 12). Mentors may access the gradebook more frequently to see alignment between student progress and pacing guides as well as review teacher feedback with the student. Indeed, in Michigan Virtual’s Mentor Guide, when discussing characteristics of a good mentor, mentor Lyn DeCarlo states, “Check-in with each student every week: pull up your gradebook, go around and check their progress, see their feedback — at their seat. They like that.” The gradebook offers a way for mentors to monitor student progress, encourage self-regulated learning and the development of metacognitive skills (e.g., using feedback from instructors), check in about any difficulties, and celebrate wins. Reviewing the gradebook with the student, at their seat, as DeCarlo states, may also create opportunities for rapport building which is important considering that ‘building relationships with students’ was the most commonly cited “top three” effective mentoring practice (18.9%) and monitoring student progress was the second most commonly cited “top three” effective mentoring practice (17.8%).

Effective Mentorship Practices

Relatedly, there was alignment between the practices mentors perceived as effective and research on mentor responsibilities and reported practices. The top three practices reported by mentors as being the most effective were ‘building relationships with students’ (18.9%), ‘monitoring student progress in their online course(s)’ (17.8%), and ‘motivating students to fully engage with course content’ (10.0%). Borup’s (2019) conceptualization of mentors facilitating the student learning process through nurturing them, monitoring and motivating them, and facilitating communication align well with the majority of current findings. The exception is that while Borup (2019) considers facilitating communication between parents, students, and instructors one of the three big categories of mentor responsibilities, the mentors surveyed in this study did not report a high frequency of communication with teachers. However, mentors did rate their communications with instructors as being very effective, which may suggest that instructors and mentors were able to work together effectively when the situation warranted it. These practices also align with the experiences of effective mentors who contributed to the Mentor Guide. Indeed, multiple mentors stressed that “the key is having a relationship with students” because it is important for students to know they have someone on their team who has the resources and experience to help them succeed. Additionally, monitoring and motivating students seems to go hand in hand as Julie Howe notes how important it is to “Closely monitor students and course content, and ensure students are engaged in activities that promote their academic progress.”

While mentors’ frequency of communication with students was in line with recommendations, communication with instructors was less consistent and perhaps represents an area for follow-up (Lynch, 2019). Mentor communication with instructors can help contextualize student behaviors. For example, a mentor may notify the instructor if a student is sick and logging in less frequently. Further, establishing a line of communication between the mentor and instructor may help the mentor better understand instructor feedback and more easily encourage communication between student and instructor.

Taken together, mentors are supporting students in a variety of ways, including but not limited to building relationships, monitoring progress, and motivating engagement with course content. Oftentimes, mentors carry out these responsibilities with approximately 30 students, although mentors working in schools where >75% of students qualify for FRPL, and mentors with 5+ years of experience are likely to have more students assigned to them. There were slight differences between the survey and SLP data, such as a similar median number of students being assigned to mentors working in buildings classified where >75% and <25% of students qualified for FRPL. These differences may reflect the fact that mentors self-selected to participate in the survey.

Administrators should be mindful of mentors’ student loads as the amount of time it may take to carry out monitoring and motivating students will likely increase as their number of students does. Relevant professional learning should also be available to mentors, as well as peer support, especially if there are only a few mentors in a single building.

References

Borup, J., Chambers, C. B., & Stimson, R. (2018). Helping online students be successful: Student perceptions of online teacher and on-site mentor instructional support. Lansing, MI: Michigan Virtual University. Retrieved from https://mvlri.org/research/publications/helping-online-students-be-successful-student-perceptions-of-online-teacher-and-on-site-mentor-instructional-support/

Borup, J., & Stimson, R. J. (2019). Responsibilities of online teachers and on-site facilitators in online high school courses. American Journal of Distance Education, 33(1), 29-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2019.1554984

Bruno, J. (2019, November 18). Mentoring As Personalized Learning. Michigan Virtual. Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/blog/mentoring-as-personalized-learning/

DeBruler, K. & Green, C. (2020). MVLRI research in review: K-12 on-site mentoring. Michigan Virtual. https://michiganvirtual.org/research/publications/mvlri-research-in-review:-k-12-on-site-mentoring/

Freidhoff, J., Borup, J., Stimson, R., & DeBruler, K. (2015). Documenting and sharing the work of successful on-site mentors. Journal of Online Learning Research, 1(1), 107-128. 107-128. Waynesville, NC USA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Retrieved July 10, 2023 from https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/149918/.

Herta, N. (2022, April 21). 3 Tried-And-True Tips For Mentoring Online Learners. Michigan Virtual. Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/blog/3-tried-and-true-tips-for-mentoring-online-learners/

Lynch, D. (2019, October 15). Strategies For Mentoring Online Students. Michigan Virtual. Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/blog/strategies-for-mentoring-online-students/

Michigan Department of Education (2022). Pupil Accounting Manual 2022-2023. Michigan Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.michigan.gov/mde/-/media/Project/Websites/mde/OFM/State-Aid/Pupil-Accounting/Manual/2022-23-Pupil-Accounting-Manual.pdf?rev=0823e4ecdad84ac5ba32b9b7439fcafa&hash=0CDF461FF9269C0842C3A39B29C2ED6D

Michigan Virtual. (2020, January 17). Why Mentors Matter: A Conversation With Jered Borup. Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/blog/why-mentors-matter-a-conversation-with-jered-borup/

Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute. (2020, March 27). What Does Research Say About Mentoring Online Students? Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/blog/what-does-research-say-about-mentoring-online-students/

Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute. (n.d.). Mentor Guide to Online Learning. Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/resources/guides/mentor-guide/#acknowledgements

Michigan Virtual. (n.d). Affiliation Presentation: Student Learning Portal [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/professionals/mentors/

Michigan Virtual. (n.d). Mentor Guide to BrightSpace [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/professionals/mentors/

Michigan Virtual. (n.d). Best Practices of Mentoring Online Students [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://michiganvirtual.org/professionals/mentors/

Roblyer, M. D., Davis, L., Mills, S. C., Marshall, J., & Pape, L. (2008). Toward practical procedures for predicting and promoting success in virtual school students. American Journal of Distance Education. 22(2), 90-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640802039040

Appendix

Appendix A. Excluded Building Types

| Building Type | N Excluded |

|---|---|

| GenNet | 37 |

| HomeSchool | 39 |

| Non-Michigan | 6 |

| Non-Public School | 55 |

| Not a School Building | 70 |