Introduction

More and more professional learning is being delivered online, allowing for self-paced, on-demand access to a wealth of online courses and resources. This is not without pitfalls; technological issues can also create barriers, such as the increased emphasis on self-paced education, which places constraints on collaborative interactions among participants (Educause, 2014). In 2016, with the introduction of the Michigan Virtual Professional Learning Portal (PLP), a concerted effort to create online communities of learners was undertaken. Creating these social constructivist spaces for learners resulted in multiple professional learning communities (PLCs) that were created to take advantage of the affordances of online delivery models, including ongoing and asynchronous access to discussions, resources, and peers. Each one of these communities focused on a discrete element of the educator population, providing a space for those groups to have intentional interactions around specific areas of concern that might not be addressed by wider professional learning options. The three communities analyzed in this report are the Early Literacy District Coaches Online Community (EL Coach), the Statewide Online Mentor Network (Mentor Network), and the STEM Teacher Network (STEM Teacher).

The EL Coach was established for school district coaches working in K-12 schools on the Statewide Early Literacy Professionals grant, which employed coaches to work with teachers throughout Michigan on the Essential Instructional Practices in Early Literacy, Grades K-3 literacy improvement work. The coaches met regularly face-to-face, and the online community provided a communication channel for administrators to interact with coaches in between their face-to-face meetings.

The Mentor Network focuses directly on mentors of online learners. In Michigan, every student enrolled in an online course is required to be assigned a mentor. The network is an outgrowth of efforts led by the Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute® (MVLRI®) to understand the role of online learning mentors and provide better support for professionals in this area. Originally a website that hosted resources and general information, the initiative is now an effort of the Professional Learning Services team within Michigan Virtual, providing streamlined access to resources, ongoing discussions around topics pertinent to the field, and updates on a series of face-to-face trainings that occur throughout the state.

The final online community was established to provide access to a series of live webinars created to support STEM teachers, another set of educators often geographically isolated from one another. Much of the online interaction occurred during the webinar series, but continuing education credit reconciliation for participation and access to resources was provided through the community.

This report will present findings from analyses of enrollment patterns since each community’s launch and characteristics of participating activities focused on discourse in the discussion forum. It is important to note that all of the communities in this report are supplemental spaces for collaboration tied to programs that had other avenues of interaction, such as face-to-face events, webinars on YouTube, and Twitter chats.

Conceptual Framework

The study team reviewed literature (Darling-Hammond & Richardson, 2009; McConnell, Parker, Eberhardt, Koehler, & Lundeberg, 2013; Owen, 2014; Trust, Krutka, & Carpenter, 2016) on educators’ PLCs and online PLCs, summarized key components, and now present these components in Table 1 below. Individual theme categories were investigated through observing PLC textual data (i.e., discourses in discussion forums).

| Theme | Description |

| Motivation |

|

| Leadership |

|

| Authenticity |

|

| Collegiality |

|

| Collective learning

|

|

| Focused on student outcome |

|

| Learning outcomes |

|

| Format |

|

| Technology & Skills |

|

Methods

The study explored two types of data: participants’ information and textual data participants created in discussion forums for the community. On April 30, 2018, user information, including names (anonymized for the dataset), affiliation entries, and start time records, were exported from the PLP reporting system. The study sample was comprised of 694 participants from the EL Coach, 186 from the Mentor Network, and 103 from the STEM Teacher, totaling 983 participants. Note that new participants may have enrolled after the data collection date, but they were excluded from the study.

We found the level of affiliation in the participants’ information data category to be inconsistent: some participants self-reported affiliation at the school entity level and others at the district level. Additionally, given the constraints of the systems and reported data, we did not receive substantial data on participants’ backgrounds as this information was not collected in the system. To address those challenges, we decided to supplement the PLP dataset by using data in the Educational Entity Master (EEM). Given the data we had available, we explored participants’ geographical distributions. We selected the county variable as the coding variable, which required some form of data processing, detailed as follows:

- Matching the affiliation variable in the PLP data and the school entity and district variables in the EEM set by using Excel’s Fuzzy Lookup function.

- Validating data entries when the similarity estimate the Fuzzy Lookup function calculated was less than 1 (i.e., other than the perfect match between two textual data) by manually searching for school and/or district websites.

- Validating cases when counties shared the same name as the school district by searching for school and/or district websites with participants’ reports on names and affiliations in the raw data.

In addition, the start time variable in a long date/time form was converted to the monthly form for consistency and comparability, resulting in a study sample time range of November 2016 to April 2018. Note that November 2016 did not necessarily correspond with the time when each PLP launched. We then descriptively analyzed the resultant data to explore geographical characteristics of participant distribution and growth trajectory of communities over time.

Second, we manually scraped textual data discussion forums from the two communities of Mentor Network and EL Coach. We excluded STEM Teacher from the textual analyses, as the format of that online community was different from Mentor and EL Coach in that it did not have the online discussion forum at the time of data collection. For the two communities included in the study, analyses were limited to texts discussing specific educational topics; threads such as participants’ introductions were excluded. Per the thread, the dates of the first and last postings and the numbers of replies were collected. We also calculated the discussion duration — how long a thread received replies.

Text Mining

Text mining techniques were used for the purpose of data reduction, based on the concept of the reduction of multitudinous amounts of textual data down to the meaningful parts, keywords, and their closely related words. A discourse represents a topic as a weighted set of related words. Some words are more likely to appear in a given topic, and others are less likely to appear. After creating a document of discussions, one way of representing that is to format it as a matrix that contains a list of words in the document and their corresponding frequencies. Another text mining technique is to decompose those document-word matrices that are highly multidimensional by nature to generate a smaller approximation of the original document-word matrix combined with a single-dimension group of words that often appear together. Put simply, the entire data reduction process through text mining techniques was performed for textual data to be summarized as a list of frequently expressed words and related words that were expressed together.

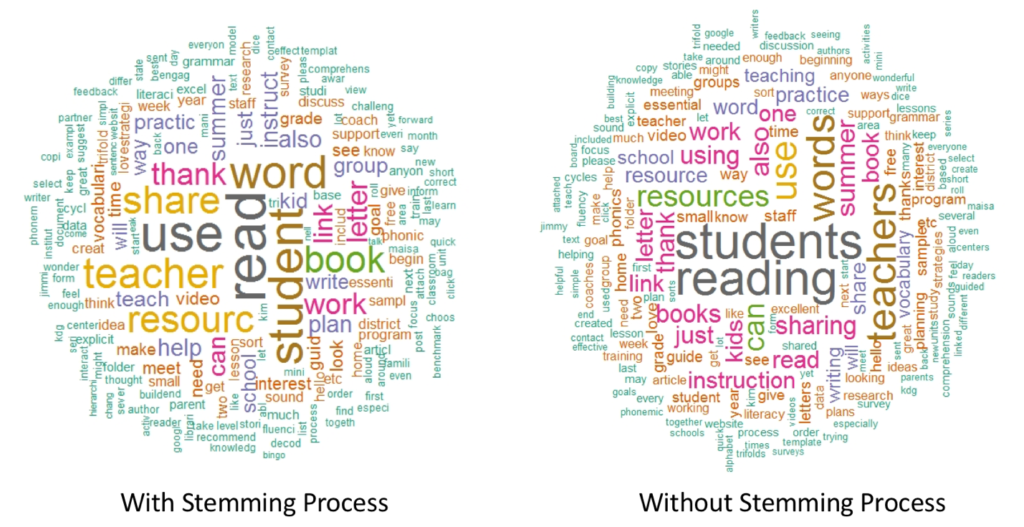

In doing so, we removed common stop words, for example articles and prepositions, from all documents to be analyzed. We graphically presented results with word clouds, and we analyzed each discussion forum twice to create two types of word clouds, one of which was for uninflected words (e.g., learn, learning, learner, and learners were all merged into the term “learn”) by text stemming. Finally, with the resultant word list, the study team conducted qualitative thematic analysis of the discourses in which those terms were more likely to appear.

Findings

Participant Information

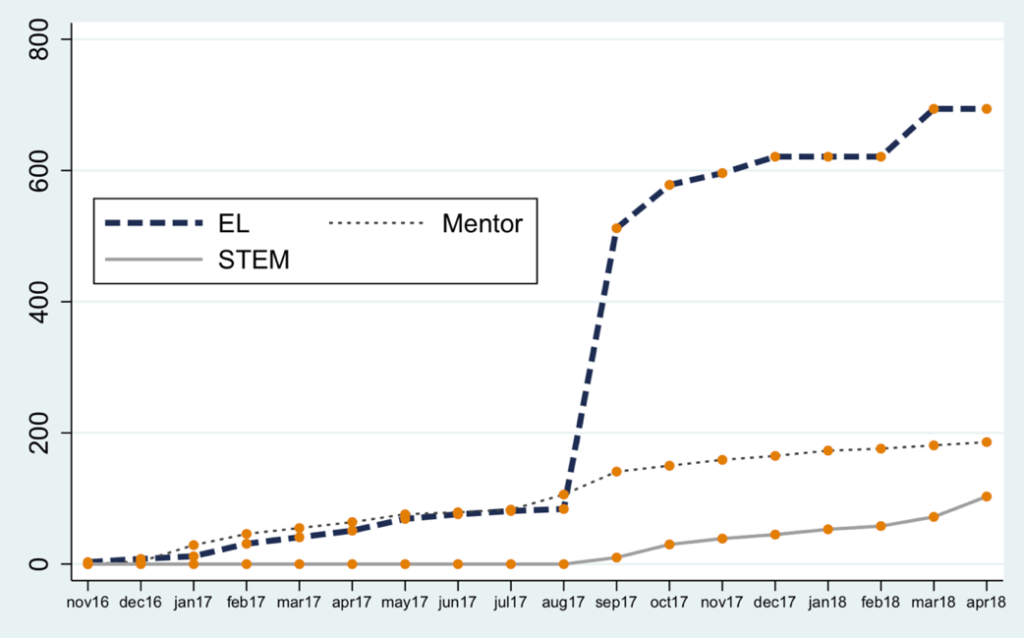

Figure 1 presents the monthly enrollment of community participants since November 2016.

The EL Coach community started with three participants in November 2016 and showed rapid growth from August (84 in total) to September (512) 2017. At the time of data collection, the total number of participants had reached 694. Mentor Network members started to join in December 2016 and showed a similar growth pattern as the EL Coach community’s during the time period’s first half. With a gradual increase in the given time period’s last half, the Mentor Network community ended up including 186 participants. The STEM Teacher community launched in September 2017 with ten members. After a gradual increase, 103 members are currently contributing to the community.

The Mentor Network and STEM Teacher communities’ growth was organic, with members joining as they signed up for events and other non-online community activities. The EL Coach grew quickly in August 2017 as members were added as part of a statewide initiative to train literacy coaches throughout Michigan. The community was used to store resources for the first two groups of coaches to go through training in August and September 2017, and every coach was encouraged to enroll in the online community.

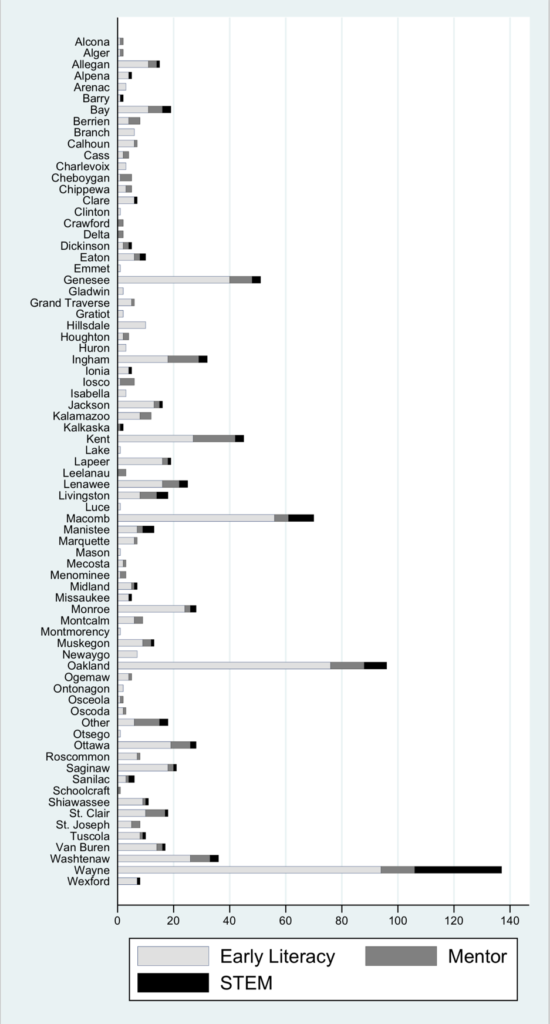

Figure 2 summarizes participants’ affiliation reports by county.

Overall, more participants were from relatively large counties. The number of school entities in the top ten counties – namely Wayne, Oakland, Macomb, Genesee, Kent, Washtenaw, Ingham, Monroe, Ottawa, and Lenawee – ranged from 62 (Monroe and Lenawee) to 754 (Wayne) and exceeded the average across counties (54.8) in the study sample. This enrollment pattern is unsurprising given that eight of these counties fall within the top ten most populous counties in the state. Similarly, nine of the top ten learner affiliations (school districts) within the Michigan Virtual’s PLP fell within the counties detailed above. The state-funded early literacy district coaches’ professional learning grant has allowed rural districts to hire coaches, which probably attributes to the higher number of total rural counties with enrollments in the early literacy community.

Textual Data

Textual data, in the form of discussion board posts were also analyzed for this study. Descriptive findings as well as evidence of thematic categories are discussed below.

Mentor Network

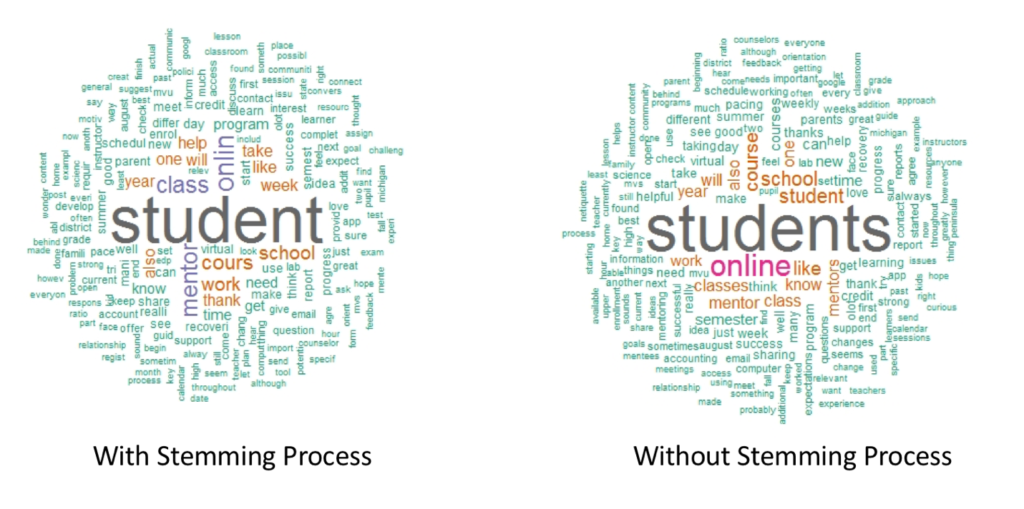

Figure 3 are the word clouds presenting key words that were most frequently uttered in discussion forums for the Mentor Network community.

The Mentor Network participants created six topic strands: (a) General ideas and questions, (b) Starting a new term strongly, (c) Annual mentoring calendar, (d) Michigan Virtual public knowledge base, (e) Credit recovery, and (f) Fully online programs. The participants discussed those topics in 34 threads, which contained 166 posts. Individual threads appeared to contain an average of four responses to the initial post (range = 0 ~ 17 replies to the initial post). The average date range from the initial posting to the last posting in a thread was 68 days, with a maximum of 296 days at the time of data collection. We found two threads that received 17 replies in total. One titled “Key Topics for an August Virtual Mentor Convening” was initiated in February 2017 and received its last reply in July 2017, before the event was held (duration = 49 days). The other thread titled “Use OLOT for Students Waiting Enrollment” could be characterized as long duration (296 days), as it was initiated in February 2017 and received a reply in December 2017. The first thread was dated January 2017.

The most common keyword in the mentor community was “student.” Words that were closely correlated to it included “online” and “course.” When postings containing those words were observed from the lens of our conceptual frameworks, we noticed some of the utterances in the discourse on student learning and/or change, for instance, providing them with avenues for success in the online learning environment or intervening when they fell behind in the course. Another participant discussion strand using those key words was interpreted as authenticity, given that conversations focused on providing students with better options, opportunities, or resources and advising them about study motivation and course engagement using pacing guides and progress reports.

However, the community did not seem to advance in-depth conversations about specific examples and strategies to monitor student progress or motivate and engage students. Accordingly, we did not consider the authenticity theme as deeply as bringing evidence, student work samples, or artifacts collected from the classrooms to lead the discourse and analyze the data collectively, which should have led to conversations dedicated to pedagogical change.

Those findings reflected the nature of the Mentor Network community. It has served more as a repository for resources for mentors of K-12 online learners, providing updated information on policy and research and links to guides, trainings, and other assets of value. Activity within the community is usually spurred by face-to-face training events conducted by Michigan Virtual staff; participants in face-to-face training are encouraged to join the online community, post an introductory post in the discussion board, and explore the resources available. The community is also used to promote upcoming face-to-face events. Often the mentors that participate in trainings relay that they prefer face-to-face interactions over online opportunities. A select number of mentors within Michigan have been chosen to serve as “Regional Mentor Leaders” to help facilitate discussion and activity within the community, but this initiative has not generated as much activity as planned. Michigan Virtual should consider a more focused and dedicated approach to serving the online community if it wishes to increase activity. Those contexts explained a lack of discourse that would be construed as authentic and leading to pedagogical change in the online discussion.

From the discourses using the keyword “mentor,” we found that the community helped members share their reflections on online education and professional identity within that context. That is, we noticed its three closely related words – “amount,” “golden,” and “maximum” — in discourse on the mentor’s caseload and duty. Talks were not limited to seeking “a golden number,” but members shaped the content of discourse on various school contexts and, consequently, various needs in terms of mentors’ caseloads, duties, and commitments. The community also shared emotions and dispositions about their reality.

EL Coach

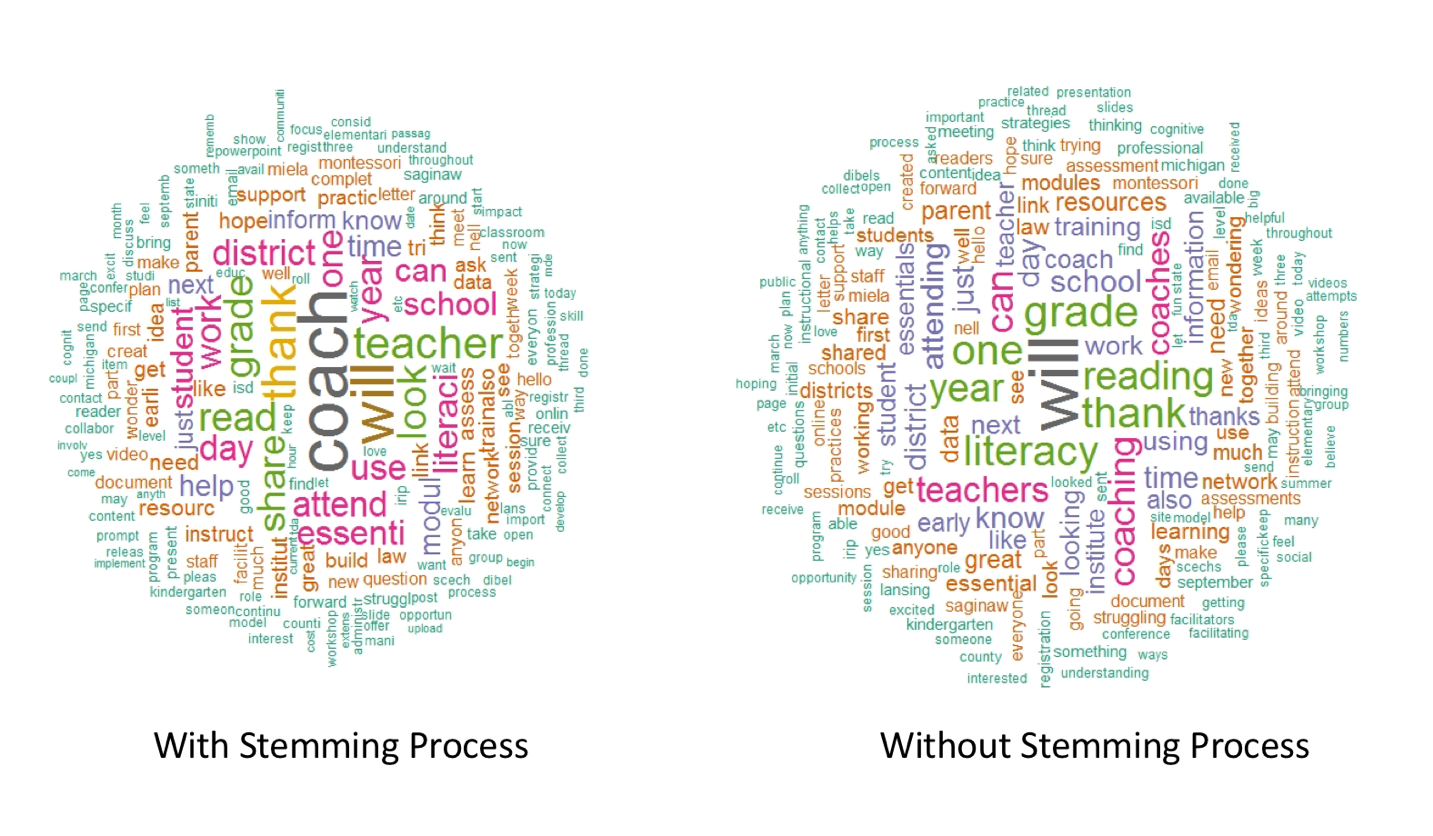

Regarding discourses in the EL Coach community, we have constructed textual data in two ways: one with educational issues and the other with conversations prompted by Essentials course contents. Figure 4 are the word clouds for the first data set, the educational topic discussion.

The EL Coach participants conversed with each other in five topic strands: (a) General discussion area, (b) Interacting with administrators, (c) The third grade reading law and assessment lists, (d) Grant opportunities, and (e) New coaches, a place to share. The five topics consisted of 48 threads containing 198 posts. All posts that initiated a thread received three replies on average, ranging from 0 to 31. In terms of receiving a reply since the initial posting, the EL Coach community’s threads lasted for 23 days on average and up to 365 days at most. The two longest threads were “Are you attending the MiELA Network Institute?” receiving 31 replies in 38 days and “The Third Grade Reading Law & Assessment Lists,” with 11 replies in 36 days. The first thread was dated December 2016.

In the whole corpus that EL Coach participants created, “coach” and “will” appear to be uttered most frequently. For “coach,” utterances were noticed in the discourse about effective coaching practices, which enabled us to code those mentions as elements of student learning and/or change and as authenticity. Members created in-depth conversations by repeatedly mentioning (pre and post) data collection practice focused on student achievement and teacher instructional practices, indicating the component of pedagogical change.

Also, the corpus contained the remarks, “I could send you what that looked like if you would like an example,” “If you would, I would like to see examples of the surveys you sent out to staff. Thanks!” and “Could I get the examples, too?” As such, we learned that the EL Coach community exhibited collegiality and supportive and shared leadership.

We found another example for collegiality and, in turn, collective learning, in several connected postings using the word “coach” and its closely related words, such as “anywhere,” “cohesive,” and “graphic.” The initiator asked for help locating a graphic resource for a defined coaching role that was presented in a conference meeting for her to share with her administrators. One responder shared similar resources, and another expressed a willingness to contact her colleagues. The importance of cohesion across the district in defining coaches’ roles was emphasized; therefore, it is quite clear that the features of collective learning and cognitive outcomes were retained throughout the corpus. The word “will” and its closely related terms, such as “share,” “collaborate,” “ reach out to,” and “willing to” reiterated that members devoted a great deal of their discourses to sharing resources and expertise and collaborating as a team in the community.

With literacy coaches often isolated in districts throughout the state, a joint space to share resources and insight into their practice as a professional community allowed literacy coaches to both meet in person, at quarterly trainings, as well as continue dialog online. The community was also used as a tool to allow intermediate school district coaches, who are a main communication conduit for the Michigan Department of Education and grant administrators, to connect with district coaches online to disseminate information. Two grant-employed facilitators participated in answering community questions, while Michigan Virtual provided capacity to share archived training resources, including video of face-to-face training, through the community.

Last, by the same method, we also analyzed forums in the EL Coach community that had been prompted by Essentials’ contents; the results are presented in the preceding pages. The Essential Instructional Practices in Early Literacy is a research-based daily practice to improve literacy instruction created by national early literacy experts for the State of Michigan. Essential topic areas were pre-determined and designed for four categories: (a) K-3 Essentials discussion with ten topic areas, (b) Pre-K Essentials discussion with ten topic areas, (c) Coaching essentials discussion with seven topic areas, and (d) School- and center-level Essentials discussion with ten topic areas. Among them, topic areas for which the community generated threads are summarized in Table 2, and Figures 5 present the word clouds from discourse on those topics.

| Category | Topic Area | Thread | Post |

| K-3 Essentials | Deliberate research-informed efforts to foster literacy motivation and engagement within and across lessons | 1 | 3 |

| K-3 Essentials | Read aloud of age-appropriate books and other materials, print or digital | 3 | 17 |

| K-3 Essentials | Small groups and individual instruction, using a variety of grouping strategies, most often with flexible groups formed and instruction targeted to children’s observed and assessed needs in specific aspects of literacy development | 3 | 11 |

| K-3 Essentials | Activities that build phonological awareness | 1 | 2 |

| K-3 Essentials | Explicit instruction in letter-sound relationships | 7 | 18 |

| K-3 Essentials | Research- and standards-aligned writing instruction | 4 | 13 |

| K-3 Essentials | Intentional and ambitious efforts to build vocabulary and content knowledge | 2 | 5 |

| K-3 Essentials | Abundant reading material and reading opportunities in the classroom | 2 | 9 |

| K-3 Essentials | Collaboration with families in prompting literacy | 3 | 4 |

| Pre-K Essentials | Brief, clear, explicit instruction in letter names | 1 | 3 |

| School /Center | An ambitious summer reading initiative supports reading growth | 3 | 3 |

Focused on the 11 topic areas presented in Table 3, the community generated 30 threads, each of which received two replies on average with a range from 0 to 6. The total number of posts is 88. Three threads received the maximum number of replies, and they were all created to share resources with the community, for example, website resources for age-appropriate readings, resources for explicit instruction in letter-sound relationships, and a Google Form sample for student interest surveys.

The first post was dated May 2017. The average time from the initial to the last post in a thread was 31 days, and the maximum was 191 days at the time of data collection. Three long-running threads included the aforementioned explicit instruction resources (154 days), a lesson plan template for vocabulary instruction (192 days with five replies), and resources for small group instruction (168 days with five replies).

Conversations pertinent to the theme of collective learning and, in turn, cognitive outcomes were evident in corpora containing the key word, “read.” Such phrases as “one way to think about,” “I would love to chat about,” “I would love to hear,” and “does anyone have any other” stood out in corresponding postings, which reveals that participants shared, revised, and recreated knowledge by bouncing ideas off of each other and seeking feedback from others’ perspectives. These actions indirectly involved outside experts because members conversed about particular models, articles, and programs from their schools, districts, and other professional development programs. Therefore, the words “read,” “reading,” and “readers” did not pertain exclusively to students but also encompassed educators. That is, two types of discourses coexisted: students’ reading and educators’ reading.

Regarding the proximity of word pairs, “summer” is worthy of attention. We noticed postings using both words of “summer” and “read” in the discourse to specifically describe summer reading programs and share resources, including reading lists, student activity materials, webinar notes, and links to videos. When educators did so, discourse could be characterized by the desire to become a more reflective practitioner (professional identity), volunteering to enhance the community’s knowledge base (shared leadership), being research-based (collective learning), recognizing the problem of summer loss, authenticity, and focused on student outcomes.

The EL Coach community’s creation predated the release of the online Essential Instructional Practices in Early Literacy modules from Michigan Virtual, which started to be released in October 2017. This created a short window where the only professional discourse and resource access outside of face-to-face training occurred in the community. With the Essentials document not providing direct examples of instruction, the only group dialog around practical application occurred in the face-to-face training or in the online community. As the professional learning grant matured and modules were released, more work was being done with teachers at the district level, with less district and ISD literacy coach dialog at the state level. Over the summer of 2018, discussions about the need for spin-off communities have started with the Michigan Department of Education, focused on communities specific to English Language Learners and a separate early literacy leadership community.

Discussion

With the rise in demand for online professional learning opportunities for education professionals, deliverers and facilitators of professional learning experiences must become more knowledgeable about what practices and design considerations lead to positive outcomes. Online learning allows more educators to be reached and connect at scale; the three online communities detailed in this report have allowed educators to connect with one another over great geographic distances, as well as network with professionals dedicated to a specific, focused domain of practice.

The analysis of demographic data of participants, including geographic location data, allows us to make inferences about the contexts in which certain educators participate in online professional learning. Other data, including that which illustrates the usage and participation patterns of the users in each community, suggest that while the professionals were able to connect and network, the level of depth in the connection was something to be improved upon. Moderators of online professional learning communities like these may consider how to incorporate more structure and facilitation that would generate deeper connections, more sharing of specific support strategies, and analysis of student or professional learning artifacts, that would create a richer learning environment. Additionally, given some of the more successful outcomes of the EL Coach community, providers of professional learning may consider how communities like these can supplement and serve a thriving community that build upon the affordances of face-to-face training events.

Future studies in this area would benefit from more detailed analysis of user pattern data, including the amount of time that users spend on certain modules, resources, or activities within an online community. Another useful group of data would be focused on users’ progression from one resource or activity to another, illustrating how users typically use the community and find value in navigating through it. Lastly, qualitative data gathered from participants might provide a more robust understanding of what exactly community members find useful and how improvements might be made to have more impact on practice.

References

Darling-Hammond, L. and Richardson, N. (2009) ‘Research review-teacher learning: What matters?’, Educational Leadership, 66 (5), 4653.

Educause. (2014). 7 things you should know about CBE tools. Retrieved from https://library.educause.edu/~/media/files/library/2014/7/eli7110-pdf.pdf

McConnell, T. J., Parker, J. M., Eberhardt, J., Koehler, M. J., & Lundeberg, M. A. (2013). Virtual professional learning communities: Teachers’ perceptions of virtual versus face-to-face professional development. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 22(3), 267-277.

Owen, S. (2014). Teacher professional learning communities: Going beyond contrived collegiality toward challenging debate and collegial learning and professional growth. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 54, 54-77.

Trust, T., Krutka, D. G., & Carpenter, J. P. (2016). “Together we are better”: Professional learning networks for teachers. Computers & education, 102, 15-34.