This resource is submitted in compliance with Section 98 of the State School Aid Act, which requires Michigan Virtual™ to “produce an annual consumer awareness report for schools and parents about effective online education providers and education delivery models, performance data, cost structures, and research trends.”

The purpose of this resource is to make consumers aware of the status of online learning in Michigan and is specifically designed to inform parents, school personnel, and school board members of the nature of online learning options, their effectiveness for Michigan students, the costs of these programs, and current trends.

Michigan’s interest in and commitment to digital alternatives to traditional instruction have a relatively long history, including more than a decade of legislation and policy development. Some key milestones along the way include the following:

Section 21f, the latest and furthest reaching online learning policy to date, expands access to digital learning options for students in Michigan by establishing that public school students in grades K-12, with the consent of a parent or legal guardian, may enroll in up to two online courses during an academic term from the courses listed in their district’s local catalog or from Michigan’s Online Course Catalog. Michigan’s Online Course Catalog contains syllabi information as well as enrollment and course dates. All courses contained in the catalog include results of a quality assurance review that uses nationally-recognized standards and performance data based upon course completion. The information in these reviews will assist parents, students, and school personnel in making the best possible choices for students.

Students interested in taking an online course should work with their school’s counselor(s) or registrar to enroll. A district may deny the online course enrollment request if:

If a student is denied enrollment in an online course, parents and/or the student may appeal the decision with the superintendent of the intermediate school district in which the student’s educating district is located.

More information about Section 21f is available through Michigan Virtual at Michigan’s Online Learning Law (21f).

Currently, digital learning options in Michigan include Michigan Virtual, cyber schools that draw students from across the entire state, and programs run by consortia and individual school districts that often make use of online courses from third-party providers. These options provide Michigan students with many paths for online learning. Some Michigan students take one or two courses from an online provider in order to supplement their brick and mortar school curriculum; this online learning option is known as a supplemental program. Some students are involved in a full-time program and take all of their courses online. Still, other students are part of the fastest-growing option—blended learning—which means the teacher integrates online resources that transform the traditional classroom.

While there may be a number of different options for K-12 online learning, one provider or model does not suit all students or districts. Determining the best option or combination of options requires understanding available online learning programs and the student’s academic needs.

Online learning encompasses different educational models and programs which vary in many of their key elements. Evergreen Education Group, a nationally-recognized leader in K-12 online and blended education research, published a set of 10 defining dimensions that characterize an online learning program’s structure and delivery, adapted from the work of Gregg Vanourek. (See Defining Dimensions of Online Programs figure below). The dimensions include:

No one type or combination of attributes is “best” or better than any other; each model simply presents its own opportunities and challenges for students and parents. Understanding the possible dimensions of online programs will help inform planning and decision making that leads to success for students.

These dimensions also provide a language for thinking and talking about blended models. While the focus of this report is not blended learning, a brief explanation may be helpful. According to the State School Aid Act, blended learning is a “hybrid instructional delivery model where pupils are provided content, instruction, and assessment, in part at a supervised educational facility away from home where the pupil and a teacher with a valid Michigan teaching certificate are in the same physical location and in part through internet-connected learning environments with some degree of pupil control over time, location, and pace of instruction.” The Christensen Institute, a national leader in blended learning research, developed a Blended-Learning Taxonomy as a categorization of existing blended learning models: rotation, flex, a la carte, and enriched-virtual. The structures for these models are created once decisions have been made in regard to each of the defining dimensions of a program. Similar to the online learning dimensions and models, the elements are not mutually exclusive, and many elements can, and do, exist simultaneously.

Online learning can be more demanding than learning in a traditional classroom. The fact that the teachers and curricular experts associated with an online course often are not known to the school or parent raises some concerns. These concerns can be addressed prior to committing to a course or program of learning. Before schools or parents select courses for their students, the providers of online content should be examined according to a set of criteria recognized as indicators of quality and effectiveness. The Aurora Institute’s (formerly iNACOL’s) Parent’s Guide to Choosing the Right Online Program recommends looking at Accreditation and Transferability of Credit, NCAA Certification, Governance and Accountability, Curriculum, Instruction, Student Support, and Socialization. (See the guide for more detailed information on these categories). Some effectiveness indicators are described below.

Accreditation is a process by which educational providers are certified by accreditation agencies. It serves as a way for schools to demonstrate that they’ve met high standards and are willing to allow outside agencies to evaluate them. It is also a valuable process for institutions like schools and districts to determine what courses are worthy of credit. When considering accreditation, the reputability of the accrediting agency is of importance.

When choosing an online education provider, it is important to understand the governing agency behind the school (state virtual school, local school district, chartering agency, etc.) and the accountability measures to which the school is held.

Some students say they get more attention and support online because the environment often requires one-to-one interaction that may not happen in the classroom. To address concerns about the quality of instruction, verify the teacher is “highly qualified.” To be considered “highly qualified,” teachers must hold a bachelor’s degree, full state certification or licensure, and be able to demonstrate that they know the content areas they teach.

Teacher/student ratios detail the number of students per teacher in each classroom or course. Note that working with students one-on-one in a classroom setting is much different from working with students virtually.

All K-12 online courses offered through Section 21f must be entered into Michigan’s Online Course Catalog. Each course entry details important course information including the results of a course review using the current National Standards for Quality Online Courses updated in 2019 by the Virtual Learning Leadership Alliance and Quality Matters or the former iteration of the iNACOL National Standards for Quality Online Courses, Version 2. Both standards can be viewed at nsqol.org.

Course completion and pass rates detail how many students successfully complete each course (based on the providers’ criteria of a successful completion). Pass rate data is publicly available for course titles in Michigan’s Online Course Catalog.

Course providers should utilize a help desk with extensive hours and be able to readily answer any questions or resolve any issues that students, parents, or school personnel may encounter when enrolling or taking an online course. The availability and quality of help offered should be considered when choosing a provider.

Online course design elements differ from traditional courses. Course design should offer more than one way to engage in and complete assignments, be more responsive to individual learner needs, provide opportunities for instructor-student and student-student communication, and include meaningful and timely feedback mechanisms. Elements and activities will vary from course to course and among providers.

The table below shows the names of Michigan entities by entity type that were offering spring courses statewide in the Micourses website. Schools offering virtual courses only to their own students are not required to submit their course syllabi to the Micourses website.

The map below shows locations in Michigan offering spring courses statewide on the Michigan’s Online Course Catalog website.

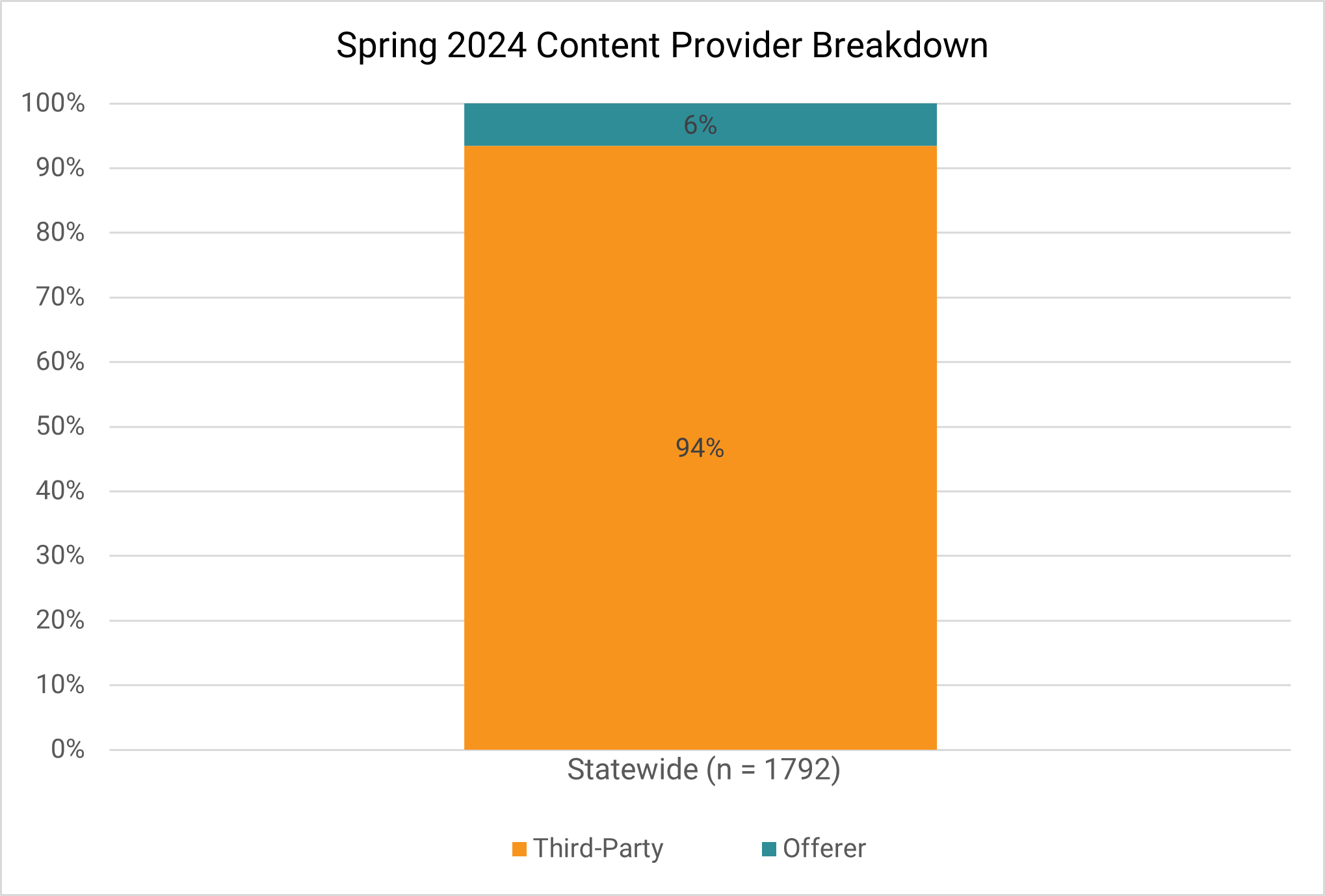

The column chart below shows how the spring statewide course titles in Michigan’s Online Course Catalog varied by course content provider.

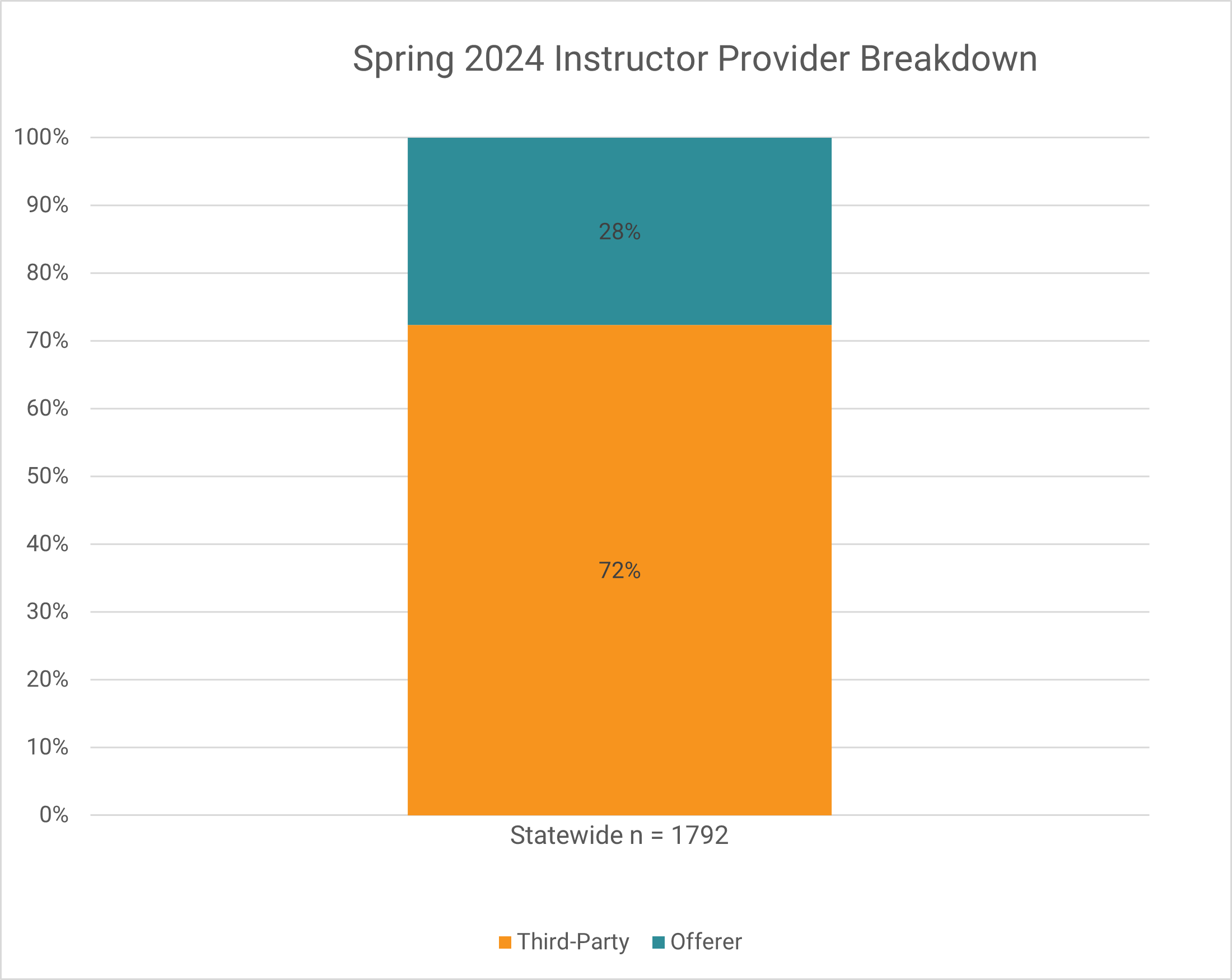

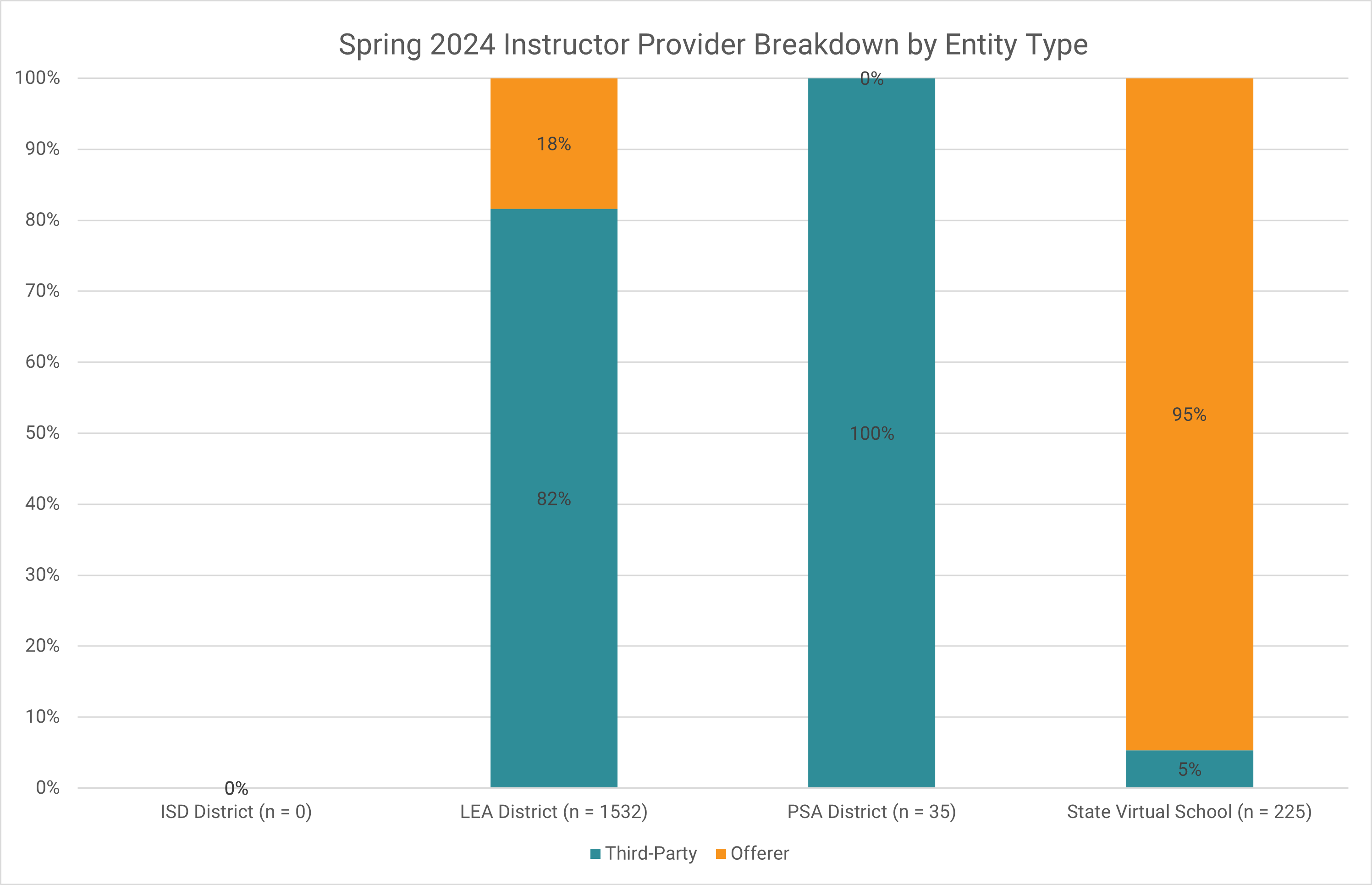

The column chart below shows how the spring statewide course titles that were in Michigan’s Online Course Catalog varied by course instructor provider.

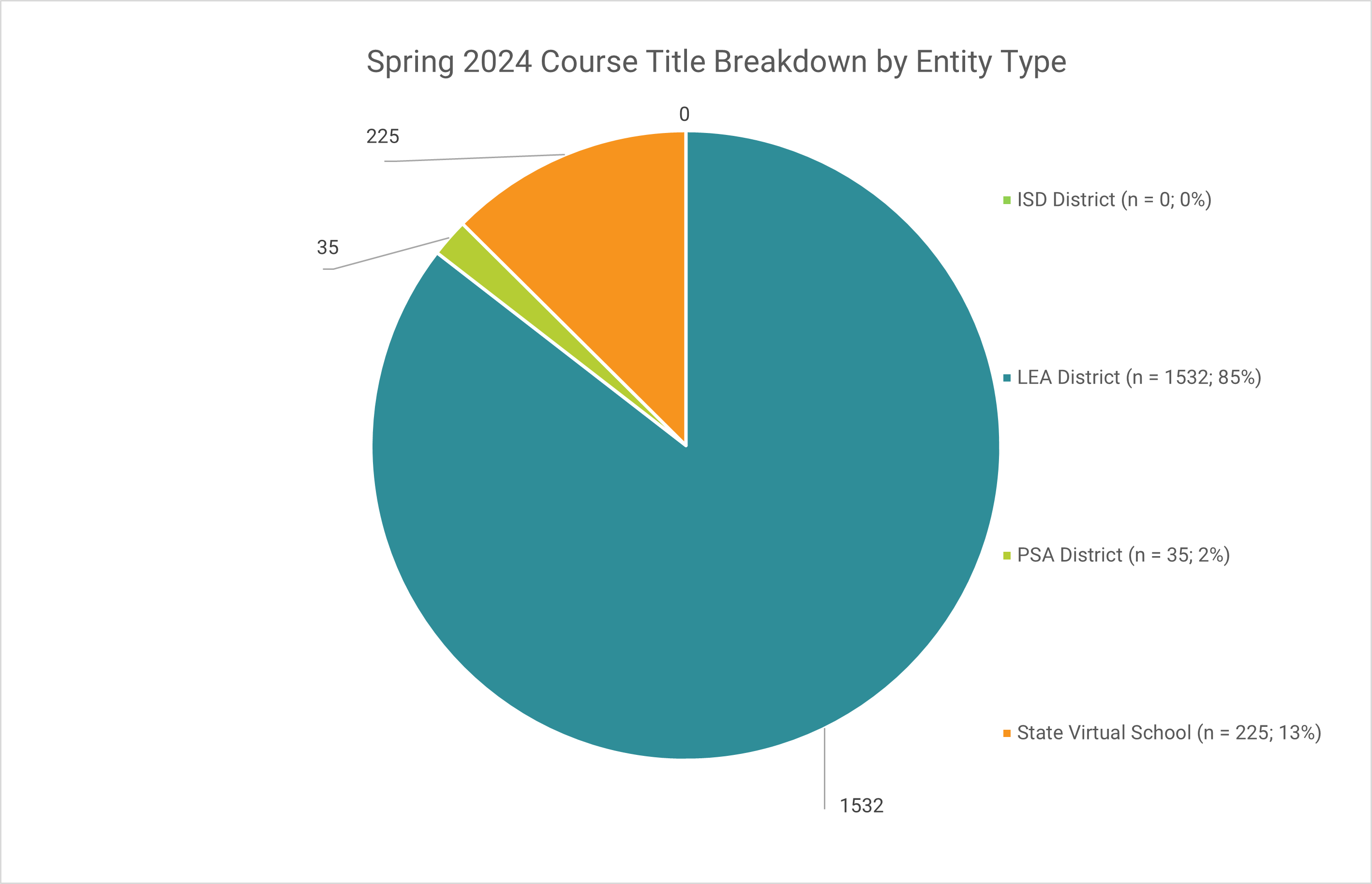

The pie chart below shows the proportion of spring statewide course titles that were in Michigan’s Online Course Catalog website by entity type (ISDs, LEAs, PSAs, Michigan Virtual). For a course syllabus to be included in the pie chart, it had to have at least one active offering within an active spring term and school year and contain the complete course review results. For this pie chart, a course syllabus is only counted once, regardless of the number of times offered.

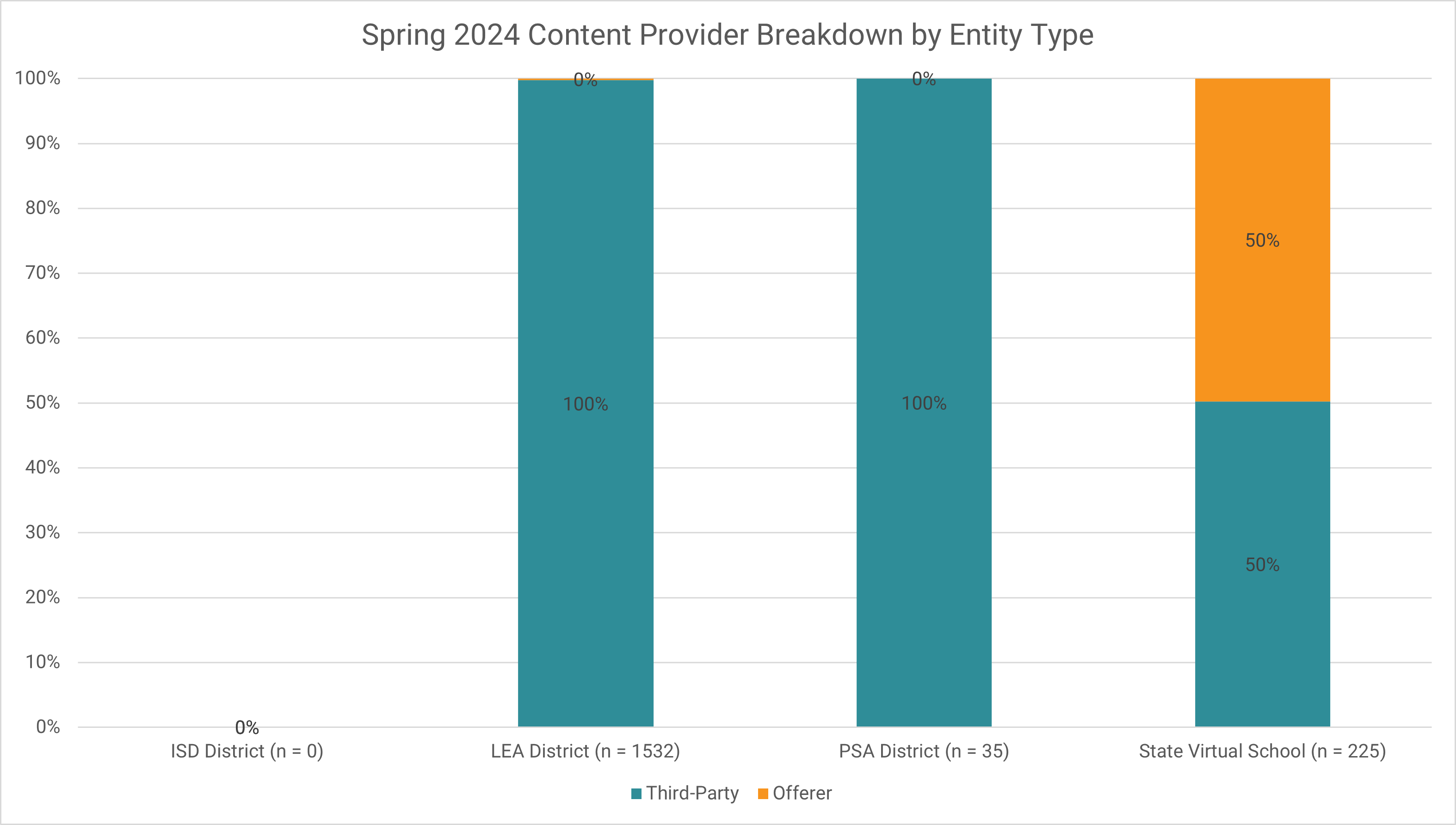

The column chart below shows how the spring statewide course titles in Michigan’s Online Course Catalog varied by course content provider and entity type.

The column chart below shows how the spring statewide course titles that were in Michigan’s Online Course Catalog varied by course instructor provider and entity type.

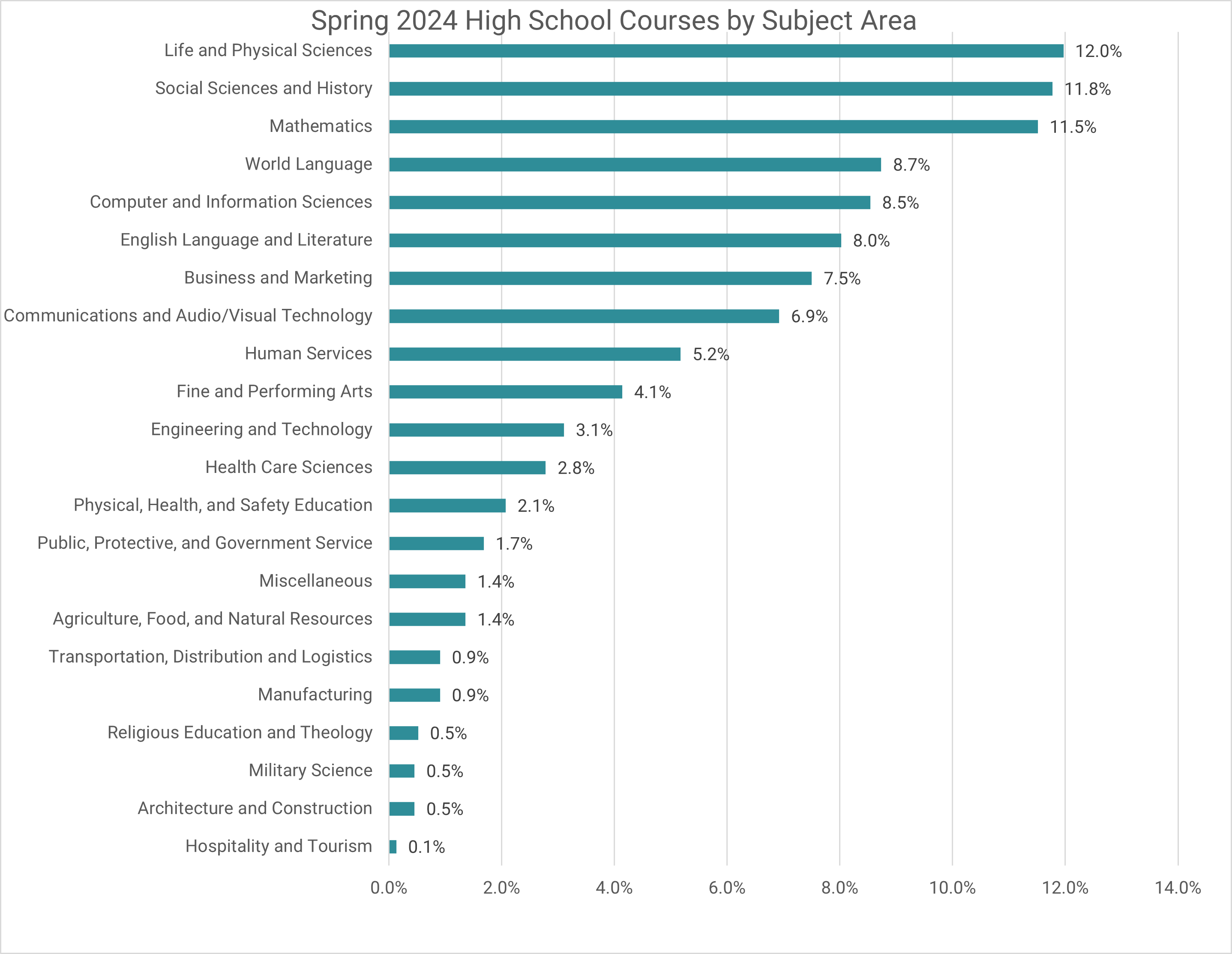

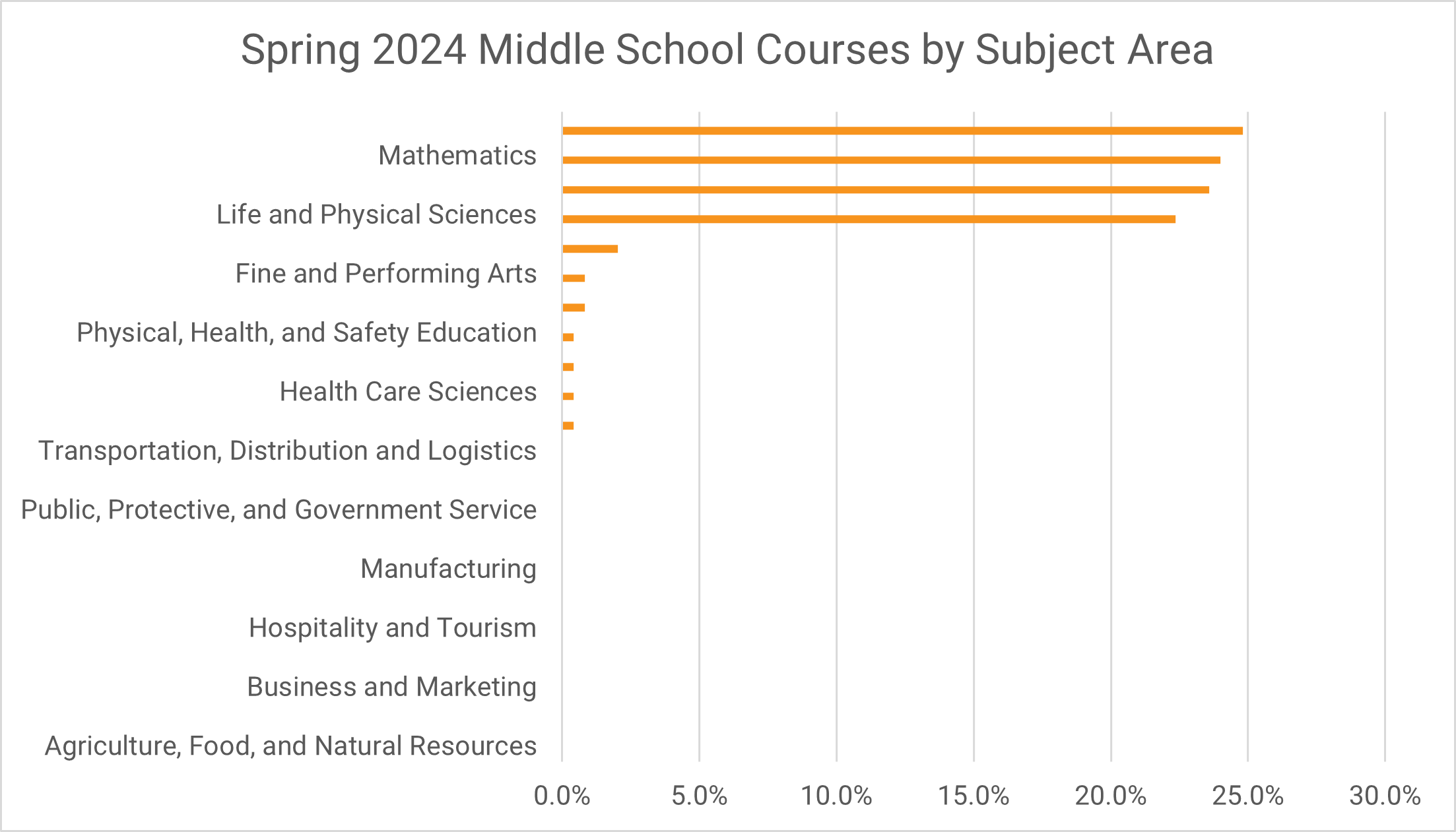

The bar charts below show the proportion of spring statewide course titles that were in Michigan’s Online Course Catalog by subject area. In order for a course syllabus to be included in the charts, it had to have at least one offering that was active within an active spring term and school year and contain the complete course review results. For these charts, a course syllabus is only counted one time regardless of the number of times it was offered.

Research supports that online learning is, on average, as effective if not more so than traditional classroom instruction. However, researchers are also quick to point out that it is not the medium (face-to-face vs. online) that matters as much as other factors like time on task, additional learning time, quality of instruction, etc. Just like in face-to-face settings, not all online experiences are high quality or even average. Those advising students interested in online learning should spend time looking at the performance data available on a provider prior to making enrollment decisions.

Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute is required to submit an annual report examining the effectiveness of online learning delivery models in preparing pupils to be college-and career-ready. The report highlights enrollment totals, completion rates, and the overall impact on students.

About 14% of all K-12 students in the state—over 208,000 students—took virtual courses in 2021-22. These students generated over 1.4 million virtual course enrollments and were present in 74% of Michigan public school districts. Schools with part-time virtual learners were responsible for the majority of virtual enrollments. Over half of the virtual enrollments came from high school students, and the most highly enrolled in virtual courses were those required for high school graduation. Sixty-eight percent of the virtual enrollments were from students who were in poverty. The overall pass rate for virtual courses (69%) was down five percentage points from the prior year but remained much higher than pre-pandemic levels.

For more information about this report, including more key findings, please visit the Research Trends section of this resource.

Like other Michigan public schools, performance data for cyber schools is available through the MI School Data website. Performance data includes sections on student outcomes, culture of learning, value for money, salary data, and the Michigan Public School Accountability Scorecard rating. The table below provides key information for the cyber schools that were open in Michigan this spring.

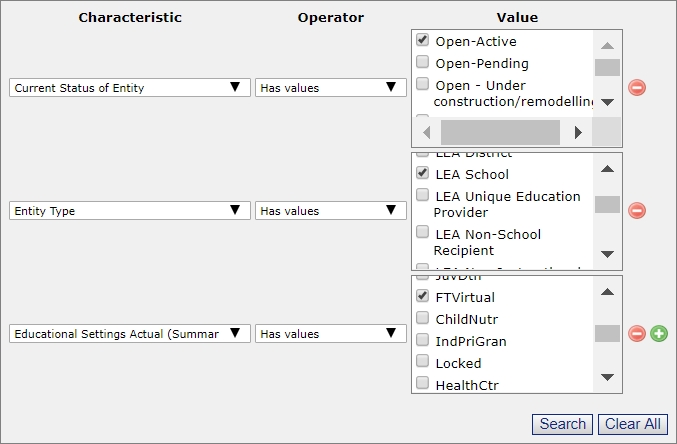

There are now 69 LEA schools across the state that offer full-time virtual learning options to district students. A full list of these schools can be found by searching CEPI’s website at CEPI Detailed Search by setting the search filters as below.

Parent Dashboard for School Transparency for each of these schools may be found on the MI School Data website.

The Michigan Virtual School is run by Michigan Virtual, a nonprofit organization. Michigan Virtual is required to provide an annual legislative report detailing, among other things, registration and completion rates by course and the overall completion rate percentage. Its Annual Reports are available for free on the Michigan Virtual website.

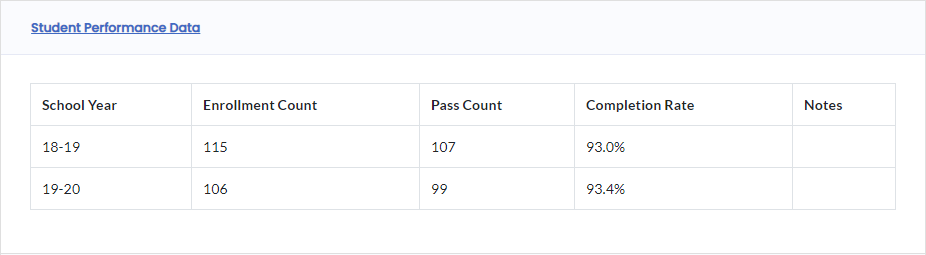

The catalog includes performance data from the preceding school year(s). This includes information on the number of enrollments from the prior year and the number of those enrollments that earned 60% or more of the total course points. The site also displays a completion rate for that year. Courses with no data from a previous year suggest the course was not offered during that year.

To view the performance data for a course title, scroll down on the page and under the “Additional Course Information” heading, click on the “Student Performance Data” link to expand that subsection.

Additional Course Information Section for Courses

Sample Data Displayed on Student Performance Data Tab

The notes field may have additional information about the performance data. For additional resources on how to use Michigan’s Online Course Catalog, see the help resources page.

Just like face-to-face schools, online providers have many of the same expenses, albeit likely in different proportions. For instance, in their paper, The Costs of Online Learning, Battaglino, Halderman, and Laurans (2010) categorize these costs into five different categories: Labor (teachers and administrators), Content Acquisition, Technology and Infrastructure, School Operations, and Student Support. The chart below illustrates the primary sources of or influences on expenditures within these categories.

The three different delivery models—fully online cyber schools, supplemental courses, and blended programs—have different cost structures because the demands of their design and operation vary. The impact on costs from common features such as course content, technology, and instructors vary, as well.

The cost of an online course is tied to the direct expenses associated with developing it or paying for it through enrollment/tuition fees, including required course materials such as learning kits or textbooks. Other types of associated expenses include indirect costs such as facilities, computers, network connections, and local mentor support services.

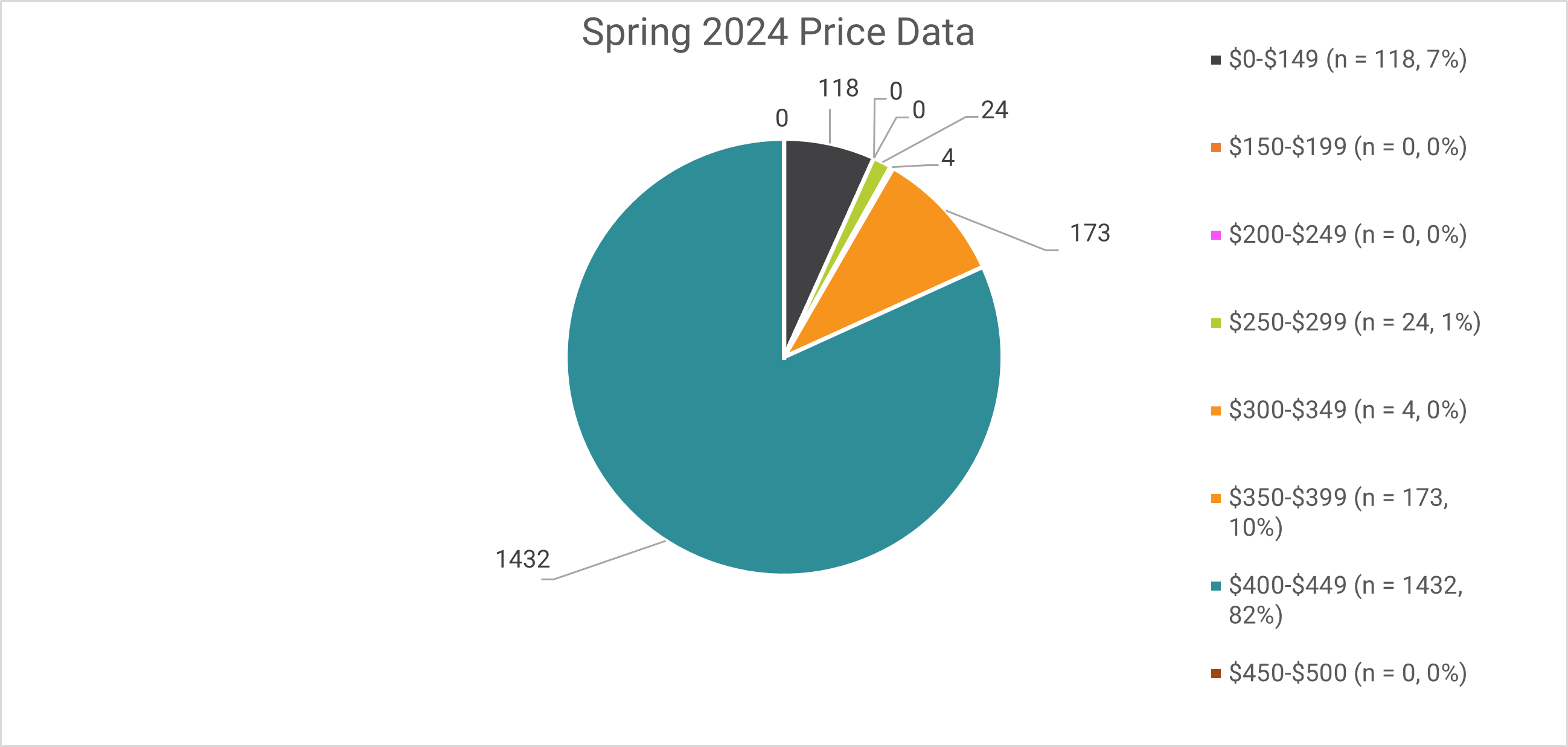

State law (Section 21f of the State School Aid Act) requires that a student enrolled in an online course must be provided the same rights and access to technology as all other pupils enrolled in his or her educating district’s school. A review of online course offerings available to Michigan students today indicates that around 96% of online courses cost between $300 and $400 for a single semester course. Students in classrooms employing blended learning use the technology available in the school and may use devices at home as well. The cost of blended learning will vary depending on whether the teacher is creating course material or the school district purchases it from a provider.

Cyber schools usually provide devices or Internet access. Their technology infrastructure will vary from that of a traditional school. On the other hand, cyber schools do not have the same expenses as traditional brick and mortar schools. Traditional schools—including those that offer blended learning—have to provide classrooms, food service, special education services, and transportation, for example.

The expense associated with instructors varies: some supplemental courses do not require an instructor; others do not include an instructor so the district must supply one. Cyber schools and blended programs will have staff expenses that supplemental instruction does not. Another important factor in determining instructional costs relates to the student-to-teacher ratio.

The pie chart below shows how the spring statewide course titles that were in the Michigan Online Course Catalog varied by course fee. In order for a course syllabus to be included in the pie chart, it had to have at least one offering that was active within an active spring term and school year and contain the complete course review results. For this pie chart, a course syllabus is only counted one time regardless of the number of times it was offered.

Research in K-12 online and blended learning continues to grow and help us understand what works and what needs improvement in various areas of the field, including design, instruction, developing new learning environments, meeting social and emotional needs of students, training educators, and more. Multiple resources are available to help keep up with the trends.

Despite the growing literature, many areas still need to be explored more deeply. In 2013, the Aurora Institute (formerly known as iNACOL) published its Research Agenda to guide the research community’s efforts from 2013-2018, and specifically recognized 10 priorities specific to future research needs in K-12 online and blended learning.

Though the opportunities presented by online and blended learning are readily apparent, more research must be done to ensure these opportunities translate to high-quality educational experiences for students.

Michigan’s K-12 Virtual Learning Effectiveness Report 2021-22

MVLRI prepares an annual report that highlights enrollment totals, completion rates, and the overall impact of virtual courses on Michigan K-12 pupils. Report findings are based on data reported to the state by schools. Self-reported data is not optimal but represents the best data that is collected to date. Some key findings from the report include:

The report findings aid educational leaders and researchers in understanding and designing subsequent studies to find out under what conditions virtual learning can and is working and leverage that understanding to cultivate virtual programs that yield the best results.

Online learning provides new opportunities for individualization and personalization of learning, flexible scheduling and location, access to highly qualified and specialized instructors, credit recovery, advanced placement, and on-demand learning. Whatever the reason for pursuing an online experience—whether it’s one course or a fully online program—students benefit academically from access to course content when they want it as well as individualized pacing and flexible scheduling matched to their current knowledge and skill. On-demand access to course content also means that parents can monitor their students’ learning and provide focused motivation and support for struggling students. Schools also benefit from increased availability of and access to online learning because they can offer more options to meet the needs of their students without hiring additional staff, often a difficult task in subject areas with a shortage of highly qualified teachers.

The transition of learning environments from traditional classroom models to any time, any place, any pace learning systems will require the transformation of both individual and organizational behavior. Michigan Virtual looks forward to supporting educational partners in accommodating these changes and working with the state’s policy leaders and elected officials to further develop Michigan’s online and blended learning industry and to help position the state to assume a national leadership role in the knowledge economy.

Below are some commonly used words or phrases that may be helpful when engaging in discussions about online learning.

Blended Learning: The Christensen Institute defines blended learning as a formal education program in which a student learns 1) at least in part through online learning, with some element of student control over time, place, path, and/or pace; 2) at least in part in a supervised brick-and-mortar location away from home; and 3) the modalities along each student’s learning path within a course or subject are connected to provide an integrated learning experience.

Mentor: An onsite mentor monitors student progress and supports the students as they work through an online course, serving as the liaison between the student, online instructor, parents, and administration. Some mentors are paraprofessionals, others fill other roles in the school such as counselor or media center director. A mentor does not always have to be a teacher to support online learners successfully; however, in many cases, the mentor must have a Michigan teaching certificate and be employed by the school district.

Online Instructor and Online Facilitator: The state recognizes two roles for teachers in online courses: instructor and facilitator. Districts must determine what the course requires and what it is they want the teacher to do and identify them by one of the two distinctions. See MDE’s Online or Computer-based Instruction for explicit definitions and delineation of the differences between the two. It is also important to note that some online courses do not include an embedded instructor — instead schools assign a local teacher as the teacher of record. Online courses without an embedded instructor appear to work relatively better for students that have demonstrated independent learning skills or have significant interest in the content area of a particular course.

Learning Management System (LMS): The password-protected LMS houses the online course. Through the LMS, students access courses and related documents and activities; assignments are exchanged between student, online instructor, and often the mentor; and communication among students and instructor takes place.

Provider or Vendor: The provider is the source of the online course. The provider may be a school, a school district, a community college, Michigan Virtual, or another third-party entity, including colleges, universities and private companies.

Credit Recovery: Some students choose or are assigned to online courses when they need to repeat a class they have failed that is required for their program or graduation.

Credit Forward: Some students take online courses to advance in their studies because their school doesn’t offer the prerequisites, for example.

Michigan Virtual™and the Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute®(MVLRI®) have developed several guides and practical resources to support school administrators, counselors, teachers, parents, and students in response to stakeholder requests gathered through surveys, focus groups, customer feedback, and conversations. As a collective, these publications are intended to inform building administrators about best practices, reduce the number of students taking online courses who fail, and, ultimately, increase the number of students who succeed.

Standards resources from iNACOL and ISTE are included at the end of this document.

The following are resources that describe standards for online teaching and learning published by organizations other than Michigan Virtual.

Note: The iNACOL publications contain clear and detailed rubrics to act as guidelines, but were recently redesigned as part of the National Standards for Quality Online Learning effort.

The Online Learning Mentor assists students with online enrollment and provides academic support while ensuring the mentoring site is functional and conducive to a positive learning environment. The Mentor must have excellent listening and conversational skills. The Mentor monitors students assigned to him or her, answers general questions, and ensures students are engaged in activities that promote their academic progress. The position requires an understanding of the high school’s history, vision, values, policies, and procedures.

For administrators who may be unfamiliar with the process for reviewing and selecting courses from a third party provider, this rubric is intended to highlight pertinent information and considerations that will lead to thoughtful, strategic choices with the students and their online learning success foremost in the decision.

The catalog of products offered by the vendor includes courses that are capable of generating academic credit in alignment with Michigan’s grade level and high school content expectations and graduation requirements.

Where State of Michigan or nationally recognized academic content standards or benchmarks exist for the subject area of the course, those standards are reflected in the content and objectives of the course.

Alignment documentation demonstrating, at the unit and/or lesson level, how and where individual standards are met in the course has been provided with the course descriptions and syllabi.

Course reviews have been conducted by Quality Matters or another third party in alignment to either Quality Matters Secondary Rubric standards or iNACOL Standards for Quality Online Courses.

School/District personnel facilitating enrollments can customize courses by selecting or opting out of portions of the course (e.g., by unit or by standard), and students can demonstrate mastery and completion of lessons, units, or standards through prescriptive pre-testing.

Course content is highly engaging, offering multiple forms of media-based instruction, interesting topics, and/or age-appropriate humor or references to pop culture, current events or enduring themes, and various modalities of student activities.

Courses have a highly coherent and easy to follow organizational structure, instruction accessible through written, audio, and video content, worked examples, interactive opportunities to practice, automated feedback and sources of remediation, identifiable formative and summative assessments, and an easy means of progress monitoring by both students and instructors alike.

The vendor’s coursework addresses in full all relevant content standards within each course.

The teacher of record for virtual learning options, as defined in Michigan’s Pupil Accounting Manual, is responsible for providing instruction, determining instructional methods for each pupil, diagnosing learning needs, assessing pupil learning, prescribing intervention strategies and modifying lessons, reporting outcomes, and evaluating the effects of instruction and support strategies.

Students can remain largely independent with regard to their work flow and ability to progress through the course at their own pace and readiness. This is accomplished through

The course design, materials, and activities demonstrate a commitment to appropriate accessibility for all students. The course conforms to the U.S. Sections 504 & 508 provisions for electronic and information technology as well as the W3C’s Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. This includes, but is not limited to:

Integration refers to the compatibility of two software applications to share data. For example, an integration between an LMS and a student information system (SIS) might mean that an LMS is capable of enrolling or rostering students within course sections by scheduled or manual uploads of student data files exported from an SIS. Single Sign-On (SSO) is another common form of integration between a secure computer network and authorized applications that run on a network. Interoperability refers to a more advanced form of integration in which data is transferred in real-time between two applications. For example, Learning Tool Interoperability (LTI) often requires that an online interactive learning tool receives course and student information from and passes back student activity data and student scores to an LMS.

[Date]

Dear Parent and Student,

We are excited about sharing information with you about new opportunities in online learning for students at [school/district].

In 2013, the Michigan Legislature expanded student access to digital learning options through Section 21f of the State School Aid Act. Now, students enrolled in a public local district or public school academy in grades 6‐12 are eligible to enroll in up to two online courses during an academic term – or more if parents, students, and school leadership agree that more than two are in the best interest of the child.

Online learning is an instructional approach that allows us to expand and customize learning opportunities for students. However, it is substantially different from face‐to‐face instruction and usually works best when thoughtful planning supports individual enrollment decisions.

To help you prepare for making the decision about whether your student has the characteristics to be successful learning online, we recommend you review the Parent Guide to Online Learning at https://mvlri.org/resources/guides/parent-guide/. The guide examines online learning, provides a preparation checklist, offers advice for parents, and will help you prepare for a conversation with your son or daughter to determine if an online learning option is best for him or her.

We also recommend you and your student review together the Student Guide to Online Learning, found at http://mvlri.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/studentguide_508.pdf. The guide includes answers to typical questions and concerns that students often have when deciding if taking an online class would work for them, a readiness rubric designed to identify areas where students may need additional support to be successful in an online class, and comments from students who have been successful in online coursework.

If online learning seems like a good fit for your student, he or she may select online courses from our local district catalog [website address] or from Micourses, the statewide catalog of online course titles available at https://micourses.org/. We are excited about sharing this opportunity with students, but equally cautious in making informed decisions so students will have the best chance of success with online learning options.

Please direct your questions related to online courses to Mr./Ms. ______________. He/she will be able to explain the process being used by [school/district] to implement the new polices that expand online learning options for students.

Sincerely,

[Name], [Title] [School Name]

[Date]

Dear School Personnel,

We are excited to share that we are developing guidelines and procedures to accommodate student/parent requests to take online courses. While we are pleased about sharing this opportunity with students, we are equally cautious in making informed decisions so students will have the best chance of success with their online learning choices. With the help of school counselors and building administrators, students will be able to enroll in courses that both fit their interests and meet graduation requirements. Students may select online courses from our local district catalog [website address], or from the statewide catalog of online course titles available at https://micourses.org/.

Online learning has become more common in part because, in 2013, the Michigan Legislature expanded student access to digital learning options through Section 21f of the State School Aid Act. Now, students enrolled in a public local district or public school academy in grades 6‐12 are eligible to enroll in up to two online courses during an academic term – or more if parents, students, and school leadership agree that more than two are in the best interest of the child. For more information about 21f, you can review Implementation Guidelines: Section 21f of the State School Aid Act, available in the 21f Tool Resources at https://mvlri.org/resources/21f/.

To help you prepare for advising students who may be considering online options and determining if they have the characteristics to be successful learning online, we recommend you look at these guides, available on the Guides page (https://mvlri.org/resources/guides/) of Michigan Virtual Learning Research Institute’s website:

The Teacher Guide to Online Learning may also be of interest to many of you and is available in the same location.

Please direct your questions related to online courses to ______________. He/she will be able to explain the process being used by [school/district] to implement the new polices that expand online learning options for students.

Sincerely,

[Name] [Title]

Schools and districts have many decisions to make about the online options they will provide their students. As with any initiative, establishing and maintaining a successful online program requires planning, ongoing oversight, and participation from internal and external stakeholders. The questions below are meant to help administrators gather information that leads to a comprehensive strategy, shape a program that meets the needs of their community and maintain a thoughtful, strategic approach to offering online options to their students.

Approximately 93% of my students who have taken an online class said they enjoyed their experience and would take an online class again, and approximately 95% of my students felt extremely supported by their online instructor. These learning opportunities are enriching student learning and growth. – Mentor

Occasionally the mentors identified superintendents as the driving force behind online programs and the development of mentor capacity. More often it was their building principals. The mentors spoke appreciatively of the willingness of their administrators to explore online opportunities and engage in developing solutions to ongoing changes, including making their support known throughout the school and sometimes defending online options.

The broad question, “What advice would you offer to administrators about online learning?” yielded four general suggestions:

I’m very lucky. My principal couldn’t be more supportive. If students are behind, and I can’t think of any other way to help, I send them to the academic counselor who sits together with the student to figure it out. If that doesn’t work, the principal talks with the student. – Mentor

Mentors should be full time. You have to be available on the weekends and evenings. You don’t want students to feel like there isn’t someone to help them. – Mentor

Johnny has a deaf uncle but can’t take sign language because we don’t offer it. All you have to see is that it’s opening the opportunity to extend to kids learning something they otherwise wouldn’t have access to at school. So many higher education programs are going to online or hybrid instruction. We need to expose students to curriculum and experiences they don’t have access to before they are paying thousands of dollars at college. – Mentor and Full-time Teacher

Deadlines and structure are not built into some courses. In order to ensure success, supports for timely completion must be provided by another means: the mentor. – Mentor