This past January, iNACOL released the report Current to Future State: Issues and Action Steps for State Policy to Support Personalized, Competency-Based Learning. Among its key recommendations for achieving transformational change in K-12 education systems is this one:

Learning models should be rooted in research about how students learn best (the learning sciences), with any redesign putting student success at the center (p. 3).

For many policymakers and educators, the term “the learning sciences” may be unfamiliar. This is not surprising since the field is a fairly new one, having emerged during the 1990s. Although much of my career has been spent working as a learning scientist, I sometimes wish there were a better name for the job, because I have found that “learning scientist” is often misunderstood as “someone who is learning to be a scientist.” However, by this point, I believe the name has stuck, and it is up to those of us who identify with this field to work harder at explaining what it is and what learning scientists can contribute toward efforts that seek to create and implement models of personalized, competency-based learning.

The best authority for defining “the learning sciences” is likely the International Society of Learning Sciences (ISLS), founded in 2002. Their website states:

The International Society of the Learning Sciences is a professional society dedicated to the interdisciplinary empirical investigation of learning as it exists in real-world settings and to how learning may be facilitated both with and without technology.

The society is widely interdisciplinary and includes members from cognitive science, educational psychology, computer science, anthropology, sociology, information sciences, neurosciences, education, design studies, instructional design, and other fields.

In other words, a learning scientist’s area of interest includes, but is broader than, learning that happens in school. I think I am not the only learning scientist to have concluded that the more we learn from research on how people learn in general, the more we see aspects of our current K-12 educational system that are often in conflict with how people learn best… if “best” is defined as motivated and active learning, resulting in high levels of skills and knowledge that are retained over time.

This does not mean that learning scientists think they have all the answers for education policymakers, teachers, and instructional designers. The learning scientists I know are keenly interested in joining forces with those who work in schools, with the goal of collaboratively developing new educational innovations that are consistent with learning sciences theory and data, but are also informed by experts in the real-world practice of schooling.

This is the same type of collaborative approach between researchers and practitioners promoted by the research alliances and partnerships of the federally-funded Regional Educational Laboratories. One of the partnerships that I manage for the Regional Educational Lab Southeast is the VirtualSC Partnership for Student Success in Online Learning. VirtualSC is South Carolina’s supplemental, state-sponsored virtual school for students in grades 6-12. South Carolina has adopted a statewide Personalized Learning Framework, and VirtualSC, led by Director Bradley Mitchell, is exploring possibilities for redesigning its program to include more aspects of personalized, competency-based learning. In supporting our partners at VirtualSC, we were asked recently to answer the question, “What does research have to say about personalized learning?”

Reports in the media, such as Education Week, about research on personalized learning tend to focus on recent efforts to gather data from schools that are explicitly engaged in personalized learning initiatives. However, another way to approach questions about research support for personalized learning is to ask, “Are the elements of personalized, competency-based learning frameworks, such as the one that South Carolina has adopted, consistent with what researchers have discovered from the field of the learning sciences? Are these frameworks supported by research on how people learn best, whether in or outside of school?”

These are massive questions to tackle, because even though the learning sciences has been officially deemed a field for only 20 to 30 years, it was born out of decades of prior research on how people learn, especially research conducted by cognitive psychologists. However, it is precisely these types of questions that learning scientists need to tackle, if we are to inform states’ efforts in personalized, competency-based learning. My answer to these questions, which I was recently asked to provide in a 20-minute presentation to VirtualSC staff, is described below; but it is not the only or definitive answer. I hope this blog post might start a conversation about how other learning scientists might answer questions about research on personalized, competency-based learning with the brief answers that policymakers need, as well as with more detailed, long-term answers that can guide innovative educational practitioners, such as our partners at VirtualSC. I would also love to hear from other policymakers and educators about how research from the field of the learning sciences could support your work.

The How People Learn Framework and Personalized, Competency-Based Learning

Beginning in the 1970s, there was tremendous growth in research on how people learn. By the end of the century, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) wanted to know what all that research had shown us. At the request of the NAS, a highly respected learning scientist named John Bransford led a group of other learning scientists in coming up with a way to summarize that research, particularly the body of research from the previous 30 years. Their work culminated in a book, which is available free, online:

The book has been cited over 22,000 times by subsequent researchers. One of its key summary statements is below:

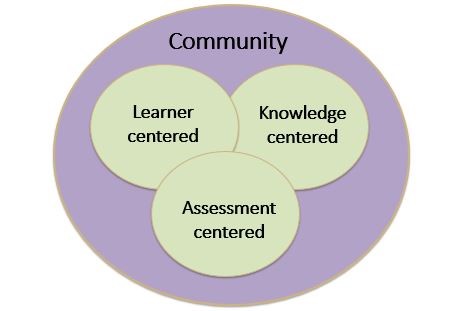

“[R]esearch on learning does not provide a recipe for designing effective learning environments, but it does support the value of asking certain kinds of questions about the design of learning environments … the degree to which they are student centered, knowledge centered, assessment centered, and community centered.” (p. 153)

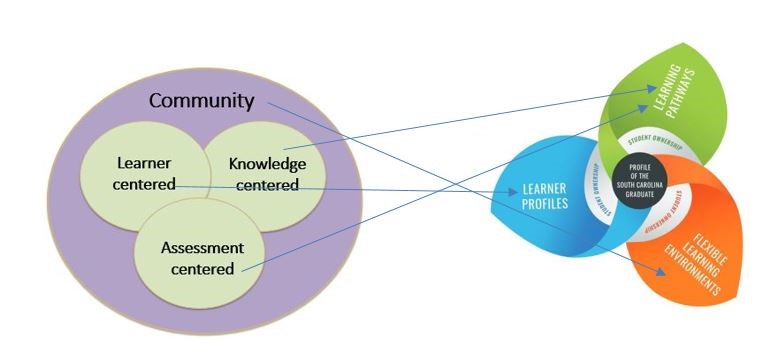

In other words, we have evidence from research that is compelling enough that a large group of scientists agreed on four important things, and here (adapted) is the way they visually represented those elements:

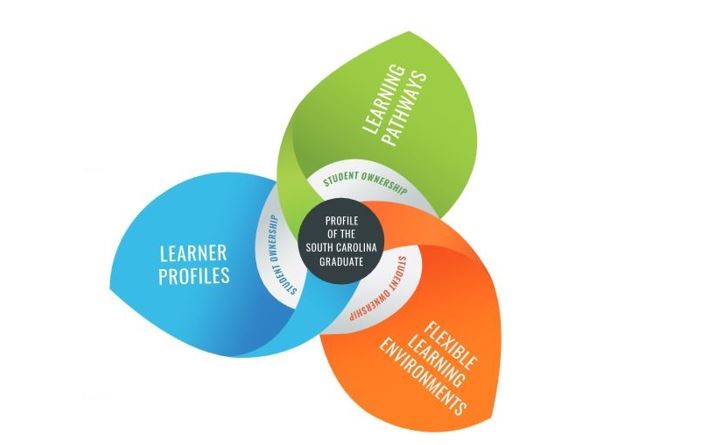

This is known as the How People Learn Framework. Notably, the terms in that framework look different than the terms on the SC Personalized Learning Framework:

Do the personalized learning elements on this framework map onto the elements from the How People Learn Framework? This is an important question, because if they do, we should feel more confident that the elements of personalized learning are also supported by decades of research evidence as agreed-upon by learning scientists.

Let’s take a quick look at how each of the How People Learn elements is defined, starting with learner-centered environments. Learner-centered environments “pay careful attention to the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs that learners bring to the educational setting” (p. 133).

That seems fairly straightforward, so let’s move on.

Knowledge-centered environments focus on learning in ways that lead to understanding and subsequent transfer.

This could use a little clarification. The term “transfer,” to a learning scientist, means the ability to use the knowledge you learn in one situation and apply it to another situation. This requires deeply understanding what you have learned. One example where this happens most often is in project-based learning environments where students spend a lot of time on a topic, acquiring knowledge and deeply understanding it. When learning environments are not knowledge centered—that is, when they have too many disconnected facts— then learners focus on memorizing things without really understanding them. Learners usually can’t use this knowledge in another situation because they don’t really understand it. Their knowledge does not transfer.

There are at least two other important things to consider about knowledge-centered environments. First, you can’t expect everyone to deeply learn everything. There’s not enough time for that. So, as an example, some knowledge-centered environments advocate designing “jigsaw” lessons around a topic, such as sea animals, so that different children read different things or do different activities to become experts on a different animal. Then children come together, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, to share what they have learned. Ideally, children become experts in something that they choose and are personally interested in.

Second, a knowledge-centered approach intersects with a learner-centered approach. Teachers need to know about the knowledge each learner has at the start of learning, to help each learner understand new knowledge. For example, if a teacher is aware that an incoming chemistry student does not understand percentages, then that teacher is more likely to help the student understand the new knowledge of chemistry by first helping the student understand percentages. Another student who already understands percentages won’t need the same type of support.

Assessment-centered environments ensure that assessments “provide opportunities for feedback and revision and that what is assessed must be congruent with one’s learning goals” (pp. 139-140).

In assessment-centered environments, assessment is not just assessment-of-learning but assessment-for-learning. Assessment is part of the learning process, not just something that happens at the end for a grade.

Finally, community-centered environments consider “the classroom as a community, the school as a community, and the degree to which students, teachers, and administrators feel connected to the larger community of homes, businesses, states, the nation, and even the world” (pp. 144-145). Learning is designed to extend beyond the classroom walls.

That was an extremely quick overview of the How People Learn framework, but I hope it’s enough to begin convincing you that there is a highly consistent match between these components and the components of most personalized learning frameworks, even though we use different terms for them. Below is one way to make that mapping to the South Carolina framework:

Personalized learning environments are learner-centered, and to create personalized, learner-centered environments at scale, you need learner profiles.

Personalized learning environments can become more knowledge centered when they allow different students to study deeply in different areas, using different learning pathways through a course. They can also become more assessment centered by designing different learning pathways depending on the support that each student needs, which becomes revealed through frequent, formative assessment throughout the course until every student can show that he or she has mastered the material.

Personalized learning environments also flexibly connect to the community outside the classroom walls. Within the classroom, students have flexible roles, just like a real community.

Closing Thoughts

To make personalized learning work, you also need student ownership. There is a wealth of research in the learning sciences on motivation and engagement related to student ownership. That body of research was too large to describe for my 20-minute talk and is also beyond the limits of this blog post. For our next steps in working with VirtualSC, we may further explore some of the areas of research related to student ownership.

I closed my presentation to VirtualSC staff with a favorite quote by Theodore Roosevelt: “Far and away the best prize that life has to offer is the chance to work hard at work worth doing.”

I’ll close this blog post with the following questions: Do you believe research supports the claim that building models of personalized, competency-based learning environments is work worth doing? Why? What other research—past or future—do we need to fully answer this question? How can we best use research and researchers as part of the nation’s collaborative efforts toward implementing and evaluating personalized, competency-based learning in brick-and-mortar and virtual classrooms?

I would love to hear your thoughts!